From our special innovation watch report in issue 30, legendary watchmaker Giulio Papi recounts the origins of his complications work with Dominique Renaud

Giulio Papi and Dominique Renaud were Audemars Piguet’s most precocious watchmakers in the early ’80s – maverick artisans engaged in constant one-upmanship. By hand, they could perfectly openwork, polish and chamfer a movement’s bridge in one minute and 50, 40, even 30 seconds, while their benchfellows took 20 minutes at least.

Nevertheless, when the two friends broke away to pioneer something as paradoxical as the innovative mechanical wristwatch, it was considered laughable. It was a time when exponentially cheaper, ultimately disposable electronic timekeeping was laying waste to the Swiss industry. But, relieved of its quotidian time-telling duty, Renaud et Papi SA soon proved that the spring-powered timepiece could be elevated as kinetic artform, capitalising on wealthy collectors seeking something with soul and eternity.

Ever since, wilfully elaborate haute horlogerie has known no bounds. Monsieur Papi himself – born in Swiss horology’s own high-altitude cradle of La Chaux-de-Fonds to Italian parents – remains no less passionate about his craft, nor the enduring interest in micro-mechanics for the sheer sake of it. – Alex Doak

Dominique and I met while working at Audemars Piguet in Le Brassus, up in the Jura Mountains’ Vallée de Joux – the Silicon Valley of the 19th century, and still the heartland of complicated mechanical watchmaking. We left the company together in 1986 to found our own workshop.

Imagine: two complete strangers starting their own company, Renaud et Papi, armed with nothing less than a dream to build complications and sell them to various makers – when hardly anyone was interested in Swiss mechanicals!

We went to see IWC, because we liked what they were doing, and told them: “Your Da Vinci chronograph with perpetual calendar is only missing a minute repeater to qualify as a Grande Complication.” A gap, to our disbelief, we were invited to fill immediately, by developing a retro-fitted, ‘modular’ chiming mechanism.

Our original plan had been to develop calibres with complications, financing these projects by selling openworked watches. We were good and super-fast when it came to openworked movements. But things worked out in a way no one could have planned for. Nobody wanted our movements, but IWC’s visionary, tragically late CEO, Günter Blümlein, had seen something else in us. (Just as he’d predicted the revival of our craft overall, rebuilding Jaeger-LeCoultre and Germany’s A Lange & Söhne in parallel.)

With this first commission, we realised we were onto something you might call ‘revolutionary’. And with legs. The musical module we developed for IWC is still in their Portugieser collection, over 30 years on. Our original employer then hired us back for striking mechanisms, as well as tourbillons – rewarding us with a majority stake in the business and a battery of cutting-edge machinery. From 1992, the sign outside our new Le Locle workshops read ‘Audemars Piguet (Renaud et Papi) SA’.

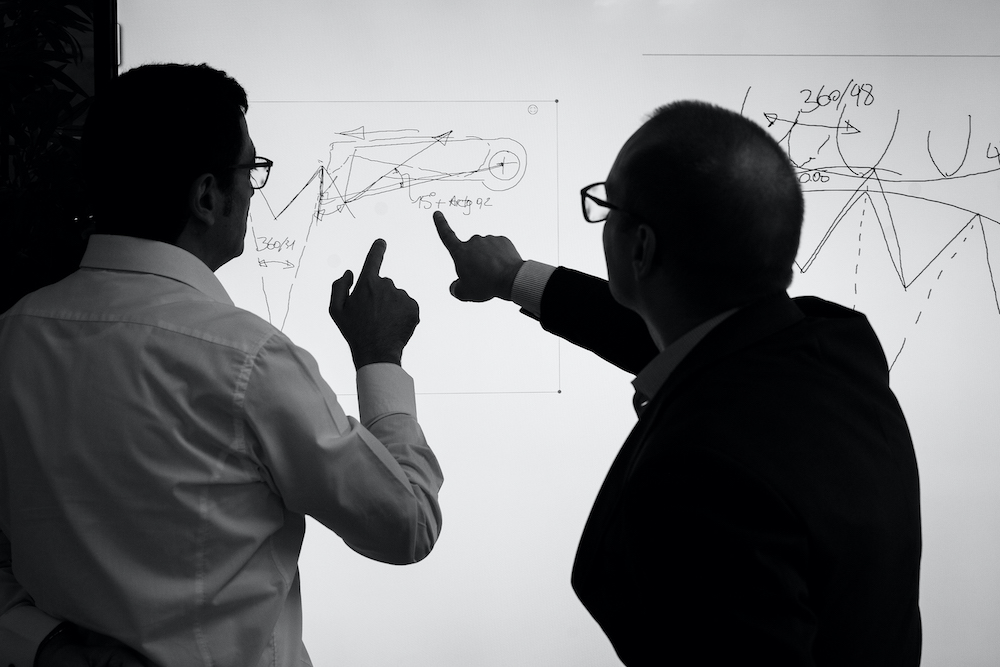

We harnessed the newfound calculating power of computers, becoming the first in Switzerland to design movements by CAD in three coherent dimensions, rather than separate two-dimensional layers. We were also nimble in prototyping parts, thanks to the flexibility and speed afforded by our computer-programmed electro-erosion machines.

By 1999, it could only be us to realise Richard Mille’s groundbreaking ‘F1’ concept of a stripped-back, futuristic ‘racing machine for the wrist’, with an engine in seamless concert with the chassis.

Again, APRP had a revolutionary notion of coherent watchmaking. People buy a Swiss watch because it appeals to them: It’s beautiful, has class, is functional, is pleasant to handle and wear. So we start with the design, to make incredible wristwatches first and foremost. Once you have the design, you construct the movement, tailoring those mechanics in perfect coherence.

With this 20th-century mindset, we turned things upside down. Quite literally, as the view through the back of a fine watch has become as valuable as the logo on the front.

Do smartwatches pose a new threat to our craft, as East Asian quartz technology did in the early ’70s? I hope not, though I cannot predict the future. But there will always be a demand for well-made things, may this be cars or bespoke clothes and shoes. Our watches enter this same category of craft. If we keep doing a good job, if we remain relevant, pushing the limits of what’s possible, there is no threat.

Other than us? Right now, Rolex are doing an incredible job. Their ratio of quality versus investment is very hard to top. Their range is less broad than what, say, Audemars Piguet has to offer, but they do it so well. Another example is Bulgari: Just look at what they have done with their extra-thin constructions. IWC, you will say I am biased because I owe them a lot. Nevertheless, technical innovation, small complications, coherence, value for money… there is something there. Some of Günter Blümlein’s soul remains present, too. The man who saw it all – and believed in us – first.

This article is taken from Port issue 30. To continue reading, buy the issue or subscribe here