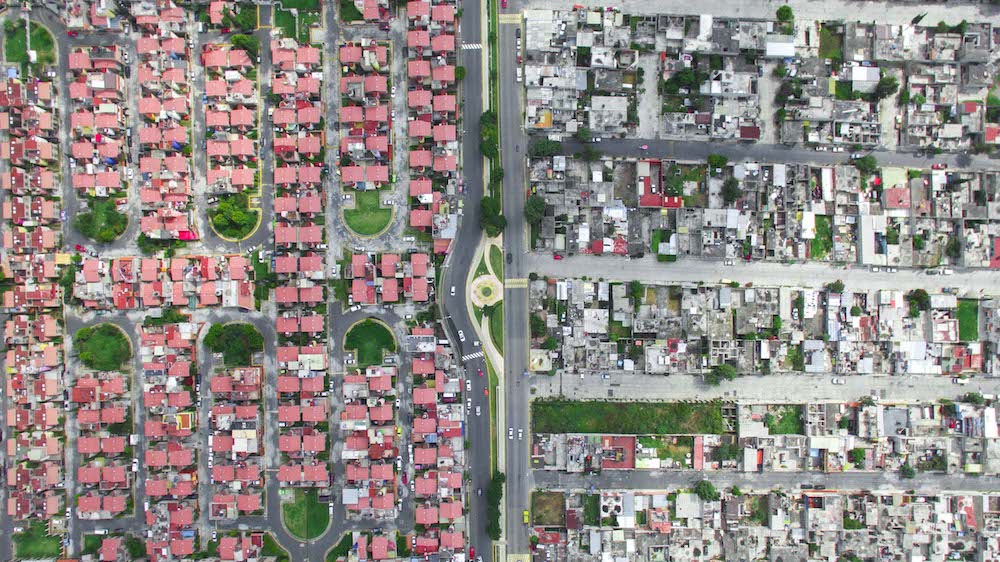

Johnny Miller’s ongoing project captures the inequalities of our cities from an aerial point of view

Technology has given way to many wondrous possibilities, like the ability to capture the world from above with the simple pressing of a remote control. Drones – the robotic aircraft that operates without any human pilot, crew or passengers – have become increasingly popular among photographers, notably for the ease and efficiency with capturing views that were previously unattainable without a helicopter or plane. Johnny Miller, who’s based between South Africa and the USA, is one of those photographers. After arriving in Cape Town in 2012 to study, Johnny decided to stay put and has been working in his medium for a total of 10 years – shooting documentary projects and lensing topics of inequality, climate change plus sustainable cites and communities. “Inequality became a much more important focus for me,” he tells me, “when I moved to Cape Town and was confronted with the reality of living the world’s most unequal country.”

In 2016, Johnny made his drone debut as he began to photograph Cape Town’s Lake Michelle and Masiphumelele communities. “These are two neighbourhoods that couldn’t be more different – a gated estate next to a township,” he explains. “I was just operating on instinct at the time, I didn’t really know what I would capture, and I certainly didn’t have a ready-made audience. Once I took the photo, I put it on Facebook with the caption, ‘Today, I’m starting a little project on inequality’. The photo blew up overnight and went viral.” This was the moment that his ongoing project Unequal Scenes was borne; a photographic series illustrating the inequalities written into the urban fabric of our cities. He’s now visited nine countries as a result – South Africa, Brazil, America, India and Kenya to name a few – and with every trip, he notices the inequality rooted deep into the area’s housing and architecture. Below, I chat to Johnny to find out more about his impactful project, why he uses a drone to tell these stories, and how he hopes to achieve a global, equal and sustainable future.

What inspired you to start documenting the environment, or more specifically, the aerial views of our cities?

I’ve always been interested in the aerial view, and I love maps. Drones just made everything really cheap and easy to get a camera into the sky – I consider them a real democratic revolution in terms of how we understand our world.

I knew that Cape Town was a divided city of course, and that architecture had a big role in that. The reasons are fairly obvious to anyone who has studied South African history. So when I got my first drone, it was a natural project to pursue, especially because at the time I was looking to pursue more meaningful photography projects.

Why tell these stories through photography, and what impact will this medium have on the topic of climate change and environmentalism?

Drones have a huge role to play in understanding the human impact on our world. I see them as a real democratic revolution. Never before has it been possible for the average person to capture information about the earth, and that allows for a reckoning in terms of how it looks from above. Are there fences, roads, or other barriers separating one group from another? Why? What are the reasons behind that and how does it shape that community behaviour?

Eyal Weizman talks about the ‘inscribed humanity’ on the face of the earth that you can see from the air. This is literally policy in concrete and steel. And it’s hard to see from the ground. What I hope with this project is that of course people will begin to talk about inequality, but more than that, people will begin to better appreciate how we all interact as part of an interdependent system. You may think that you have freedom of will, freedom of movement; but look at the architecture and road network of your city from above. You are constrained by all sorts of factors: power cables, bridges and fences. These are all planned out and designed for a reason. In South Africa, they were designed for total control of Black people, which is why the project is really powerful in that context.

What aesthetic prominence does the aerial view add to the subject matter?

The ‘nadir view’ of shooting straight down seems to be much more powerful than shooting towards the horizon. I think this speaks to the project ethos, which is highlighting the world’s most egregious divides, and how looking straight down confronts the viewer in a powerful way. So that has become the de facto ‘style’ of Unequal Scenes, and all the most ‘famous’ images are shot in that way.

How do you hope your audience will respond to this work?

I hope that audiences will respond to Unequal Scenes with a sense of engaged curiosity. I think most people want to understand more about each photograph – what the unique story is for each city, each location. I’m hoping that people will go deeper than that though, and apply the project to their own lives. Even if you live in a very ‘equal’ society, let’s say in Scandinavia or somewhere like that, you still participate in a global economic system, a global environment. Or for example, we’ve seen very clearly in 2020 that the world is very connected in our public health. So I think the project has relevance for everyone, and I hope to leave people with an enhanced feeling of interdependence.

What’s next for you?

I’m continuing to develop Unequal Scenes with new locations and new imagery. I also have other drone journalism projects that I undertake often with my organisation, africanDRONE, and my partners at Code For Africa. I keep myself engaged and curious by exploring new tech and new art projects that sometimes don’t have any relevance to social justice issues at all, but are just fun to experiment with. You can find more at millefoto.com.

Photography by Johnny Miller