From sweaty club nights to pyjama-clad family festivals, Rob da Bank has spent three decades shaping the UK’s music landscape. Below, the DJ, broadcaster and Bestival founder reflects on the rise and fall of rave culture, and why slowing down might be the most radical thing he’s done yet

For those lucky enough to have danced through the 1990s, club culture then looked like it was about total surrender. You lost yourself in the music, guided by strobes and basslines rather than the flash of an iPhone. No one was filming you mid‑groove; there was no next‑day feed, no meme risk for cutting shapes badly. Just the moment, in all its sweat‑soaked, genre‑fluid glory. Today, around 400 night clubs in the UK have closed, which is more than a third of the total number. Clubs are too expensive, people aren’t going out as much, and the younger generation are more focused on health and wellness than they are drinking. And for those who do go out, they likely have their phones tethered to their hands. As Rob da Bank puts it, “Everything’s recorded”. He’s not mourning the death of clubbing so to speak, but he recognises that there has indeed been a shift. “Maybe it will just shrink to a smaller, stronger scene – like vinyl did. People said it was dead, and now it’s booming again. It’s cyclical.”

Rob da Bank, also known as Robert John Gorham, would know. A DJ, broadcaster and festival founder, he has helped shape the UK’s music landscape from the ’90s onward. He co-founded the Sunday Best club night in 1995 in south London, launching legends like Basement Jaxx and Fatboy Slim. In 2000, he co‑established Sunday Best Recordings with Sarah Bolshi, releasing artists including Groove Armada, Lemon Jelly and Max Sedgley. From 2002-2006, Rob da Bank and Chris Coco presented The Blue Room on BBC Radio 1, a late‑night sanctuary for chill‑out, electronica and undiscovered gems. And, in 2004, he co‑created Bestival with his wife Josie – a utopian, costume-loving four‑day festival that transformed the Isle of Wight into a playground of weirdness, wellness and world-class lineups (Roxy Music, Björk, The Cure, Elton John, The xx and Stevie Wonder being just a handful of my own personal favourites I was fortunate to see). At its peak, it drew 50,000 people and scooped multiple UK festival awards before folding in 2018.

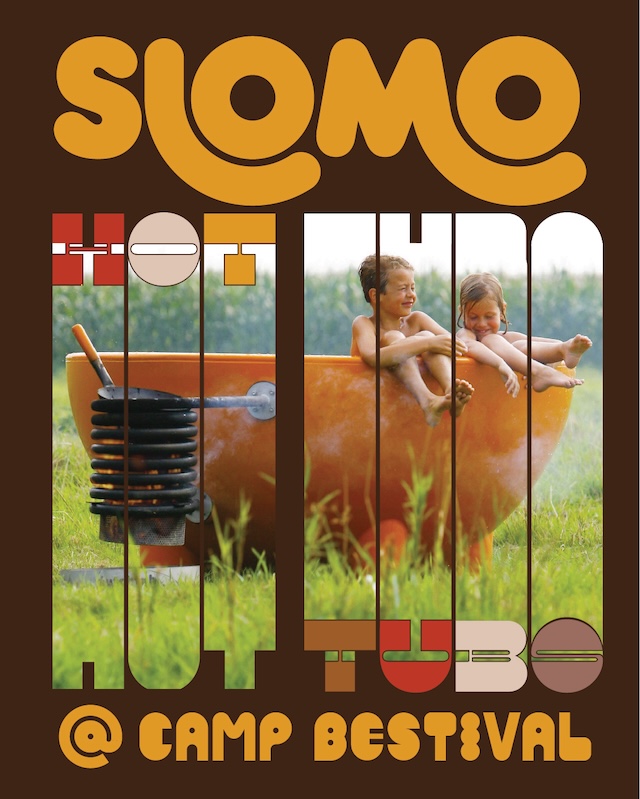

But the party didn’t end there. The couple’s offshoot event, Camp Bestival, launched in 2008, continues to thrive as a family-first affair with just as much heart. Now in its 17th year, the next edition (held on 31 July-3 August at Lulworth Castle, Dorset) features a pyjama party theme and sets from Basement Jaxx, Sugababes, Sir Tom Jones, Goldie and a healthy dose of glitter-fuelled chaos for all ages.

In this interview, Rob da Bank reflects on the early days of DIY parties, the rise and fall of Bestival and his current chapter that still includes DJing and festival-throwing, but now also ice baths, saunas, self‑discipline and slowing down with his wellness brand Slomo.

You’ve had quite the journey – from clubs to festivals to wellness ventures. Let’s rewind a bit. Was it university where things really started taking shape?

I suppose I was always a bit of a party starter. I wasn’t the class comedian, I wasn’t sporty and I wasn’t academic, so by the time I was 15 or 16 I was looking for how I could stand out. That’s when I started putting on beach parties. Then when I got to London, I became more and more into it. I didn’t have a plan – I wasn’t thinking I’d become a DJ, be on Radio 1 or run festivals. I’ve stumbled into everything I’ve done. But I think it all stems from me and Josie loving making people happy, whether through music, festivals or wellness. There’s something in both of us that just loves creating good vibes for others – that was always the ethos at Bestival. You walked onto that site and knew we’d made an effort to give you the best weekend ever.

Do you remember the first night you put on or your first DJ gig?

Not the very first, but I do remember early DJ sets in Southampton, where I grew up. Then later I was known for the club Sunday Best, which became the foundation for Bestival. It was in a rundown tearoom on Wandsworth Road. A bit grimy, kind of cool. Entry was £1.99 – partly a joke. At the time, pubs were still old man boozers and clubs were playing either trance, techno or hip hop. No one was mixing it up. I was like, “Why not?” That became Sunday Best’s thing. We’d play anything: house, electro, pop, funk, Bollywood. People loved it.

Were you raised around music? Or was that something you found for yourself?

I grew up in a little village, played in my dad’s brass band, so quite traditional. But my escape was listening to John Peel on Radio 1. In the ’90s, I got into the whole Manchester scene – Stone Roses, Happy Mondays – even down in Portsmouth. I got my first record decks when I was 15 or 16 and started DJing a bit. It all grew from there.

Sunday Best launched in the early ’90s – what was that scene like at the time?

I’m super nostalgic for the ’90s. It was when whole genres were being born – jungle becoming drum and bass, rave culture exploding. I’d go out six nights a week to everything: from trance raves to Fabio & Grooverider, to the Whirligig and Sunday Best, to the WAG club to see Gilles Peterson. London was incredibly eclectic. There was no internet yet – you found out about nights from flyers in record shops or listings in NME. I remember broadcasting on one of the first pirate internet radio stations called Interface in a little spot in Smithfield. They were like, “You’re broadcasting to the world!” There were probably ten listeners, but it was magical.

Who came to Sunday Best? Was it an eclectic crowd too?

Massively. Jazz heads, crusties, punks, New Romantics, pop kids. David Byrne dropped in. Björk came by a few times. Portishead played one of their first gigs there. Morcheeba were next door and used to swing in. But it never felt starry – it was just people coming for the music. We had residents like Andrew Weatherall and Harvey, which is wild to think about now. We never paid more than 20 or 30 quid, our door income was crap. It was ramshackle. Some nights were packed; other nights it was ten people and a dog.

Groove Armada played there too, right? You were clearly supporting new talent – is that what led you to start the label?

Yeah. Looking back, my life moved in phases. I started Sunday Best the club, then Sunday Best the label, then joined Radio 1, DJed more, did music journalism – all at once. I was assistant editor at a music mag for nearly a decade. I never wanted to just do one thing. I was never a good enough DJ to just go and be a club DJ. I was never on Radio One for more than one show a week, so that wasn’t a full-time career. The festival wouldn’t have kept me going all year round. I don’t know whether it’s that I’ve just got short attention span, or whether I actually just wanted to do lots of different things. I’m 51 now, and it probably drives my wife, Josie, a bit around the bender. I’m still trying to push myself into loads of new areas. Life is just so exciting. I want to climb mountains, sail ships, do saunas and contrast therapy, meditate… the lot.

What memories really stand out from those early years?

So many. Walking into Radio 1 every week and seeing John Peel, Pete Tong, Annie Mac, Zane Lowe. Being on that poster with all the Radio 1 DJs. And obviously Bestival. Running it with Josie and then starting Camp Bestival, which is still our day job. The label’s still going 25 years later, and I still DJ now and then. I love that I can dip in and out of all these different worlds.

What was the initial goal when starting Bestival?

We were obsessed with other festivals like Glastonbury, WOMAD and Reading. At the time, there weren’t loads like them. Then new ones like Secret Garden and Boomtown popped up. We didn’t exactly spot a market gap – we just thought, “Why don’t we do this?” We’d been throwing parties for years, had hosted the Radio 1 stage at Glastonbury, and we were really into the idea of dressing up for festivals, which no one else was doing yet. So we hatched Bestival, not realising how big it would become or how much work it would be. It was amazing, but it was also a beast.

How did you curate the lineup each year?

Because I was on Radio 1, I was always looking for new music. That was Bestival’s DNA, to have strong headliners and a big undercard of breaking acts. Ed Sheeran, Florence, Friendly Fires, alt-J – we gave them space when they were coming up. I wouldn’t take credit for breaking anyone, but I think we definitely helped some acts reach new audiences. I didn’t even realise Stormzy had played until someone showed me footage. We were the first to really embrace grime, with a dedicated grime stage before anyone else was doing it. We liked pushing boundaries.

Was curating a festival like curating a radio show?

Definitely. I just dug into my musical brain. I didn’t overthink it, I just booked what I loved. Having a budget to bring together Lee Scratch Perry, John Martyn, OutKast or Aphex Twin was a dream. We went after my fantasy list. Elton John and Stevie Wonder were near the top, and we got them. Others we chased but didn’t land – Kate Bush, Prince, Dolly Parton. But we had an incredible hip hop run too like Beastie Boys (twice), Snoop, Missy Elliott, Wu-Tang Clan. That was a proud chapter.

What led to the end of Bestival?

Festival culture became saturated. There were more and more events like us, and our audience had other options. We started losing that “flavour of the month” feeling. That coincided with some financial trouble – liquidations and horrible business stuff. It got dark. We never got into it for money, so it felt like a sad way to end. Luckily, we’d already started Camp Bestival in 2008. As we had kids, we wanted a family festival where you could still have fun, but without the 5am bedtime and chaos.

Is that why Camp Bestival has lasted?

If Bestival hadn’t hit financial trouble, it could still be going like Parklife or Boomtown. But Camp Bestival suits where we are in life. It’s not easier, but it’s more wholesome. It aligns with how we live now. Our kids have grown up with it – from our 19-year-old in London to our youngest who’s eight. It’s a family thing now.

Let’s talk about your latest chapter: wellness. You’ve launched a sauna project on the Isle of Wight. What inspired that shift?

We’ve always been into wellness. Josie and I learned yoga and meditation in our early 20s. It’s not like we hit 50 and thought, “Let’s go woo-woo.” But hedonism did start to catch up with us, and we needed more balance. That’s how our project Slomo started, originally called Slow Motion. It’s about slowing down. Saunas, ice baths, contrast therapy – it’s huge in Scandinavia and we’re just catching up. It’s not just about sweating and freezing, it’s about meditation, yoga and daily rituals. We want it to become one of the UK’s most respected wellbeing platforms, both physically and digitally. It’s a lifestyle, like Bestival was, just with a different focus.

Would you say festivals also contribute to wellness, in a way?

Absolutely. It’s still escapism. Festivals are about stepping outside real life, entering another world, connecting. That’s why we still do Camp Bestival and still love it. I still DJ in Ibiza, still go to Glasto. We’re not saying, “Give up drinking, sit in a sauna and be holy.” It’s all about balance. I’ve struggled with it, but I think I’ve found a pretty good one now.

Do you think club culture is in danger? Has it changed too much from when you started out?

Of course it’s changed. But not necessarily for the worse. Back then, people were having mind-bending times – for better and worse. If my kids lived like I did, I’d be worried. There’s more awareness now about drinking, mental health and anxiety. Social media adds pressure. In the ’90s, you could go out for four days and no one would know. Now everything’s recorded. I don’t think it’s the death of clubbing. Maybe it’ll just shrink to a smaller, stronger scene – like vinyl did. People said it was dead, and now it’s booming again. It’s cyclical.

Do you think the constant filming in clubs is affecting how people party?

Yeah. People are too self-conscious to let go. Some clubs now ban phones, which helps. But I’m not being fuddy-duddy – phones are everywhere. Still, if you’re being filmed all night, it kills the vibe. People need freedom to lose themselves, not perform for cameras.

What are you excited about for the upcoming Camp Bestival?

This year’s fancy dress theme is pajama party, so everyone’s in PJs all day. Headliners include Basement Jaxx, Tom Jones and Sugababes. It’s fun and for all ages. But what I love most is seeing people arriving who’ve never camped before, never done a festival. Families pop so many cherries that weekend. It’s wholesome, full of free stuff like tree climbing, woodcraft and sculpture building. Not just a beer tent and bouncy castle – it’s a dream world for kids and grown-ups alike.

How do you usually find new talent now? Has social media changed the process?

Weirdly, it’s made it harder. Back in the day, I’d get bags of records delivered, and that was it – a finite amount to listen through. Now it’s endless. Spotify, SoundCloud, Bandcamp… it’s overwhelming. Everyone and their dog’s releasing music. I love discovering new artists, but it’s harder to filter. Still, with Sunday Best and our electronic imprint Silver Bear, we’re putting out some really cutting-edge stuff. That’s still a buzz for me.

Any new ventures on the horizon?

I’m trying not to take on more, but I’ve just started managing an artist – a young female singer-producer I’ve become obsessed with. Never managed anyone before, so there’s a new string. Life should be varied. It’s not for everyone, but it keeps things exciting.

Last one – what’s the story behind your DJ name, Rob da Bank?

[Laughs] I wish there was a good story. I was DJing at the tea rooms where Sunday Best started, and I needed a name for a flyer. I asked the barman, Ben – I’d love to find him again – and he said, “Call yourself Rob the Bank.” It got misprinted as “Rob da Bank” and stuck. A stupid joke that’s lasted decades.