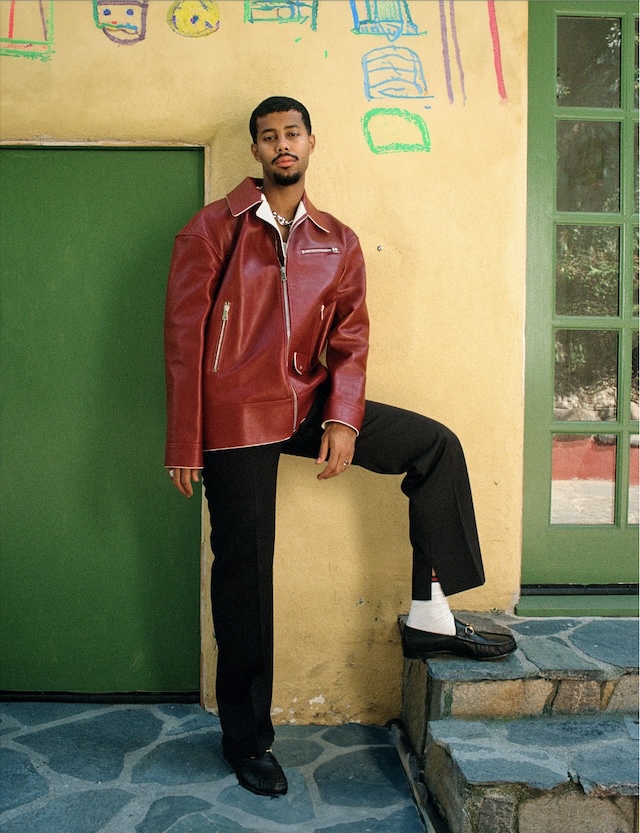

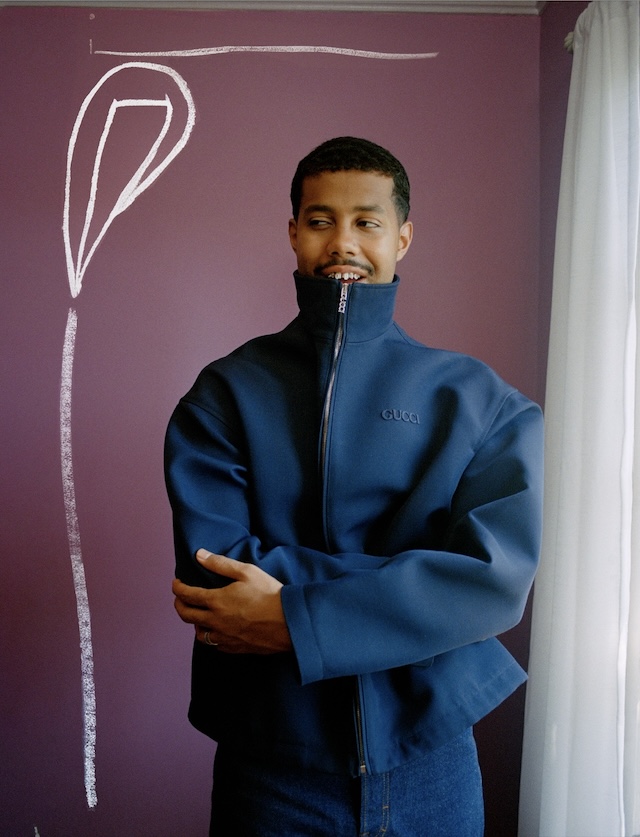

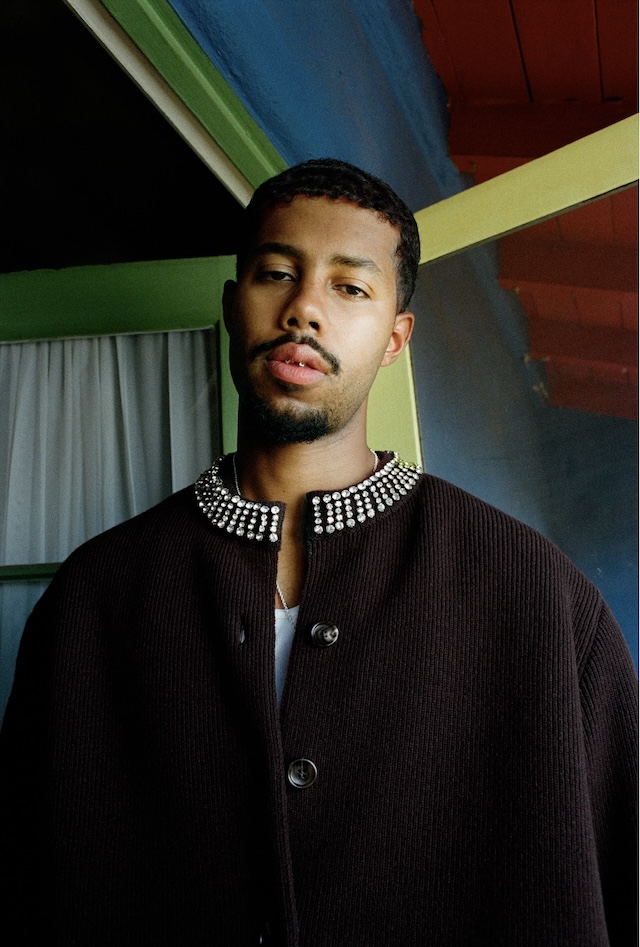

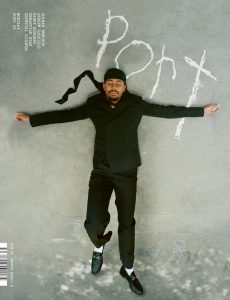

After the release of his 2021 debut When Smoke Rises, Mustafa reached acclaim for his personal songwriting exploring themes of love, loss and conflict. As he launches his forthcoming album, the Sudanese-Canadian musician sits down with friend and collaborator Dev Hynes, of Blood Orange, to reflect on his creative process, the importance of preservation, and the making of Dunya, which translates from Arabic to “the world in all its flaws”

Dev Hynes: Your new record is sick, it’s fire.

Mustafa: Thank you, man; that means a lot. You’re the first friend that has the full record, which is wild. But it’s good, and it comes out in about a month. I’ve got to start tearing myself into this new period.

DH: It’s funny because when you’re working on music that people will obviously hear, it still feels weird when you realise people are going to hear it.

M: Yes, absolutely.

DH: How old is the oldest song on the record?

M: The oldest songs are maybe four or five years old when I recorded them in Egypt. The writing is the oldest; some of it is eight years old. Concept is always first for me, and the writing has always reigned supreme.

For so long in my life, I had to develop a sonic identity – something that felt intrinsically connected to me. And luckily, Nubia had so much for me to pull from, like in Sudan and Egypt.

When I was a child, I listened to very sparse music and many of my favourite records didn’t have much production, they were so desolate. I remember referencing Sun Kil Moon and the song Carissa. There is nothing but really lonely guitar lines, and everything was riding on the story being told. When I’m writing, I’m pulling from poetry that I would have written when I was 20 years old. Of course, it would be refined and reimagined in relation to the lyrics.

DH: Do you know what you want to talk about and then write it, or is it more that the writing informs the general feeling?

M: I would say it’s more the former than the latter. I know what it is that I want to say and I’m able to identify things that I want to talk about, but it’s usually so broad that the writing needs to narrow it down. I thought I wanted to write about God, and then I realised that God is in everything I could talk about; I couldn’t have chosen a more general idea. But then it grew with its own footprint, because it’s about Islam, and Islam in the context of the hood. It became more of a secret as I began writing it.

DH: Are you a title-first person?

M: I couldn’t find a title to save my life. I struggled [with this album] in such a way I can’t even describe to you. I don’t know why, but I’ve always been really bogged down by the idea that songs have to be restricted by a title. Also, I’ve noticed that some of the most expansive titles are never in English. Growing up, I was constantly learning about the limitations of the English language, and I think that’s why I ended up choosing an Arabic title for the album. But I have a really hard time naming anything. I wish I was better at it.

DH: The titles are so direct, I love that so much – like ‘Beauty, End’ and ‘Hope Is a Knife’. I love that energy.

M: Thank you, man. I have some audacity to be that definitive. Sometimes I really enjoy titles that are contemplative, that fill a lot of space and have their own kind of bravery because they’re so specific. There are so many titles that I love that have a different kind of power. You have to be confident in your decision when choosing titles. But it means a lot. Your titles are beautiful.

DH: Thank you, I struggle with that too.

M: No, you chose one of the greatest band names of all time. Blood Orange is one of the best.

DH: That’s sick. I wonder sometimes…

M: No, it definitely is. There are some bad ones, and it doesn’t even matter if they’re bad or not. I mean, arguably the best band of all time is called The Beatles for goodness’ sake. But we don’t even think about it, because they’re so good.

DH: Exactly – I always think about that. Band names are a funny thing, because depending on what they do, the connotation gets entirely stripped.

So Rosalía and Aaron Dessner are on the album… Who else am I missing?

M: There are a lot of people on the record. Nicolas Jaar worked on a few songs, and Rosalía came in on I’ll Go Anywhere, and she fucked with the arrangement a little bit and re-sang some parts, but that was written in Egypt already. Dessner is such a prolific player when it comes to indie folk records, and he replayed a lot of the songs with some musicians in upstate New York. I then reimagined those renditions again. It wasn’t the most ideal post-production process, but it got me where I needed to go. I was following my intuition.

While working on the record, I knew something was missing, and then I heard the masenqo played by this young Ethiopian musician. I returned to nights spent by the Nile River when I was really young, and I remember hearing it seep through the open atrium to the sky, where my family used to gather in a village in Sudan. I realised it was necessary to have the masenqo on the album alongside the oud, so I brought in a young East African player to play it.

It wasn’t even a matter of what was good and what wasn’t. I was trying to be as careful as possible, because I was removing a lot of production that people did. It was less about what I imagined was great and more about what I imagined was true to the story that I was trying to tell. So much of it is rooted in longing for this part of me and this place that my family escaped from that I want to return to. A lot of the sonic decisions are a returning, in a way.

DH: Another reason why I really like the album is that it sounds like it’s landed somewhere.

M: That means so much to me, man.

DH: It’s a really beautiful feeling. You don’t get that from a lot of records, they’re usually very particular. Your record has its own world, it’s like a real thing.

M: That’s the largest compliment I could have received from you. For me, it was not for the sake of having my own world, or some attempt at having agency over a space. There was a space in the world that I didn’t feel was reflected, and much of that was the space that I grew up in. I really wanted to soundtrack what that felt like and try to develop some sort of sonic foundation or memory.

Also, the diaspora as an idea is going to transform. When I think about that, it’s like a fire beneath me, because I’m of this Sudanese diaspora. Sudan is experiencing the worst refugee crisis in the world where 10 million people have been displaced. Everything that I say and write now, that becomes, for better or for worse, this sonic memory. I realised that I needed to place a flag in the ground of what that feeling is just for this archival sake.

My issue is never about being forgotten. It’s more about being remembered in the wrong way or being misrepresented in the course of history. So I really appreciate you saying that about its own world. I think it’s a world that lives and breathes. My biggest fear is that I do it justice.

DH: I totally got that. Did you ever lose drive and need to find it again while working on the record?

M: Yeah, for sure. There were so many periods where I started to question the importance of music.

DH: I relate.

M: It’s wild. It just feels like deification has become an intrinsic part of music now. It’s almost as if, without this praise from the larger world, music doesn’t have the same function. I wish it was more casual, that it was just another form of expression that didn’t have this capitalist edge or uppercut in the way that it does. We all know that music is being monetised. We used to exchange it for our survival and now it blurs the lines of what makes a true artist. I think about that all the time.

I try to remember that I began with aspirations of being a poet when I was 12 years old, and that I chose that because I needed an outlet for the pain. I wanted to quit so many times. I didn’t feel like I had time to make the record without the grief interrogating me over and over again, where old wounds were being reopened. It’s this weird concept of wanting to remember the pain without having to relive it, and wanting to remain open to what comes in without having to open the wound. It’s definitely my brother’s murder that really derailed me [his brother Mohamed was killed in a shooting last July]. I remember sending my manager a message and saying that I didn’t want to put out the record. Immediately after, I thought there was no hope around anything that I wanted. Hope is such a critical part of the writing.

When my brother passed, it took three or four months for me to be able to return to these songs and to feel any kind of connection to them. That definitely set me off my path, but I realised that so much of why I create is about preservation. Sometimes I don’t feel like I have what it takes to tell anybody who someone was, and I get afraid that I won’t do their memory justice. That’s the thing that I tussle with, maybe more than anything.

DH: The fact you’re thinking about it means that you are doing it.

M: I appreciate that.

DH: I’m trying not to sound like an old head, but one thing that is real across the board is how the monetisation of music has somewhat stripped away how powerful music can be. It’s being consumed in a very different way but people are still affected by it. It’s done this weird thing where people that create music now question it and think, well, why am I doing this? I’m very happy that you pushed through and did it because it’s so beautiful, and I think a lot of people will feel very comforted by what you’ve made.

M: Thank you. I’m energised by what you tell me, and that’s always been fuel for me in the past as well. I realised that it doesn’t matter how much you think you know yourself, what you believe in, what you’re willing to fight for and what your moral stance is on all things moving in the world. If you are in any kind of proximity to someone that has conflicting beliefs, it begins to infringe upon the thing that you think you know. It’s so important to be around people that can reaffirm to you the path that you’re on, especially now with the kind of collapse that we’re living in. It’s like all that I have are the people that I respect, reminding me that the path that I’m on is clear and I’m there. I think that’s always been the litmus test.

I remember you writing Negro Swan when you were writing about grief. It’s wild because I would have met you in that period, and I felt so moved by what you were saying. The crazy thing is I wasn’t going to release another song for another six years but, at that time, the violence in my community was at a high that I’ve never seen since I was really young, and I was beginning to internalise it. For Negro Swan, I remember you writing a note about grief in relation to Blackness. I remember probably the first ever text I sent you was about how that impacted me. I really do remember periods like that where I listen to a record, and I read a letter around the record, and it means such a great deal to me.

Sometimes I try to remove myself from the equation and think about the possibility of what a song can be. I think about the hood and how I grew up in it, and what it would mean to my dogs. I’ll get calls from my friends in jail – they have so much time for themselves that it could become their enemy if they’re not using it and finding a rhythm in it. That’s when they could really hear my music; they’re in the horror of a judicial system that doesn’t recognise them in their humanity, so when they get a period to listen to music, I’ll get a call every now and again. And it really impacts me. What it tells me is that it’s not even for them when they’re still in the grip of the kind of violence that we grew up in, but that they’ll be able to find it once they leave it. That I pray one day that it’s not a call I get from prison, but it’s a call I get from a kind of solace that they find far outside of the hood.

Those aren’t the kind of calls I get as of yet. But this is maybe telling of a future that I’ll be able to move into. I try to believe in what the music can serve and who the music can serve a decade from now. That’s what I try to think about.

DH: Did the sonic sound of your album develop naturally as you worked on the songs, or did you always envision where you wanted it to go?

M: I listened to so much American folk music and was inspired by you and everyone from The Roches – I love The Roches so much – to Cat Stevens who was, of course, a very large reference point for me. Even Leonard Cohen, this Canadian giant, and how free he was in his writing. I knew I had a responsibility to link it to my homeland. But all the while I knew that there were flourishes and swells that had to come from a place that wasn’t entirely my own, so that’s why I went to Egypt. When it started to formulate, it didn’t make sense in my mind. I didn’t hear it completely, because I didn’t know what it was going to sound like. It was almost like painting in the dark, and I didn’t know what the painting would be until the lights were on. All I could do was be patient and see what would come as a result of it.

Also, the oud is a main character. It’s not an instrument that traditionally makes space for a top line – but in this album, the oud leads the way and you follow suit. I also included Sudanese string arrangements which are really abrasive and they take up a lot of space. I wanted the oud to follow these guitar lines, while also having the guitar play in the nature of the oud. So much of it was trial and error in arriving at a place.

Moving forward, I’m still very much exploring this intersection, and I think it’s going to take me a lifetime. One of the most inspiring things for me about you is that you’re a great artist, and you’ve been a great artist for so long. You’ve been patient, measured and integral, and that’s all I’ve ever wanted for myself. I was so impatient for a spike. This lifetime journey as an artist, to me, is the greatest luxury. So much of it is about arrival and about existing as an artist. I can’t wait for the moment where I’ve put out multiple records, but right now I’m just in this constant state of exploration.

I remember going to your concert in Toronto with two friends of mine who had never heard your music before. The only concert they had ever gone to was for this guy named Rylo Rodriguez. The most beautiful thing about it was it felt like I had invited them into a secret; there were thousands of people that had this intimate relationship with your music and with these records, and that was a conversation that they got into. They were guests to an experience.

DH: That’s the best.

M: Eventually, as things continue to form, I want to develop this secret conversation with an audience. Sometimes I sit among an audience of people, and there are so many young Muslims in the crowd that have never been to a concert before. I think to myself about how I’m going to be able to grow with them, and how I’ll be able to sharpen all of my theory around my belief system as a young Muslim person navigating this music space.

Did I imagine this sonic bed for the music that I’m making? I’m not entirely sure, but I’m still trying to reach it – it’s still over there, on the horizon and I’m going to keep reimagining it until it’s perfect. I don’t think it ever will be, but I’m going to try.

Photography Arielle Bobb-Willis

Styling Georgia Thompson

Production Mere Studios

Groomer Johnnie Sapong

Skin Homa Safar

This article is taken from Port issue 35. To continue reading, buy the issue or subscribe here