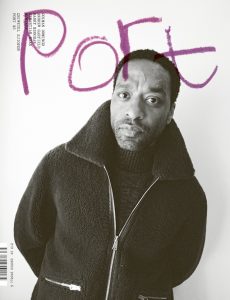

From the National Youth Theatre to Hollywood, Ejiofor talks about the influences that shaped him, the challenges of his roles and his responsibility as an artist

It’s a bright, warm day when I arrive at the photoshoot in Hampstead, north London, and though he’s wrapped in layers – the shoot is for the AW edition of this magazine – there’s a soft and comfortable smile on Chiwetel Ejiofor’s face. He crosses the room to meet me with a firm handshake. He’s got a calm, easy presence. Despite being born in east London to Nigerian parents, I recognise the movement and rhythm of a man raised in south London – his slow, considered walk, the urgency with which he attends to and listens. Our time together quickly confirms what comes to mind when I think of him, see him acting on screen or watch his directorial work: to be in the presence of Ejiofor is to be in contact with a quiet, devastating stillness. I say quiet and not silent because I think to be quiet is to inhabit a certain frequency, one which contains presence and invitation, rather than absence and refusal. So much of this emerges in the honesty with which he confronts each moment. “One cannot evade themselves,” he tells me, and in turning inward, he encourages those around him to do the same.

This theme of self-confrontation can be traced to Ejiofor’s early years, when he was around 10 or 11. An introverted child, artistic channels began to feel like the only places he could express himself. Through the muddle of prepubescence and into adolescence (those ages where words don’t ever seem to be enough for the emotions we experience), he found in performance there was space, not only for the complexities of emotions, but the exposure of them too. In this way, early on, he was already practicing a type of vulnerability required to express emotions in front of loved ones and strangers alike. Teenagers find their worlds growing at a rapid rate; Ejiofor’s grew exponentially. He found his audience as he worked with the National Youth Theatre, travelling up and down the country, featuring in shows, noticing how life opened up for him in a tangible way. “That feeling of going up on stage, and meeting people after a performance,” he says, “your life and whole point of view expands at such an interesting rate… I was hooked.”

Ejiofor cites Lennie James as a major inspiration in his early years. “I remember watching him in Lynda La Plante’s Civvies,” he says, “and it was the first time I’d seen a dramatic performance by a Black actor; I was puffed up when I came into school, doing all his lines.” When I press him on what affected him about James’s performance, he says, “role models. Seeing people who look like you, who you can relate to; relating to the complications of their experiences was so valuable.” As a child born in the ’90s, for me, Ejiofor was that role model. His performances have always struck me as dexterous, grounded yet expansive, from playing a family member in Black mob movie American Gangster to his award-winning role as Solomon Northup in 12 Years a Slave. All his roles traverse a range of genres and requirements, each with their own intensity of labour. When I ask about his preparation process and how he approaches each role, he explains he spends a long time circling, hovering and trying to figure out what’s right for the character. This can be research-based, physical or method, and often he’ll try to inhabit the most mundane moments of a character’s life in his own day-to-day. But regardless of how he travels towards his characters, it has to be with the utmost intention. “Once you start down a particular method, it turns up in the performance.”

“But it’s different,” he continues, “when I’m writing and directing, because I’ve been living with a character so long, I’m already on the inside.” This brings us to Ejiofor’s most recent artistic expression as an auteur. His first feature, The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind, which he also starred in, and which premiered at Sundance Film Festival, tells the story of a young man trying to build a wind turbine to prevent famine in his village in Malawi. His second film, Rob Peace, treads a similar ground but marks clear growth and confidence, as we follow the titular character across a couple of decades, trying to exonerate his father of a crime he may not have committed. In anticipation of our conversation, I watched his second film twice: once in the seclusion and comfort of my own home, the other in transit, surrounded by strangers on the way to meet the man himself. On both occasions, I find myself undone, watching just how far people will go for those they love. Ejiofor’s handling of a complicated, sensitive text – the film is an adaptation of a biography on Peace by his Yale roommate – is tender and considerate, while not shying away from the range of emotions and experiences which might denote Blackness. This is what becomes clear on the second watch: the care and intimacy with which Ejiofor treats his characters. The eye with which he sees, and invites the audience to see, is one without judgement, one which seeks only to explore who Black people are, what we do and why we do it.

While reading the original text, Ejiofor felt he had a real connection with the character, and he tried to foster that same sense of connection with the audience. “[By creating a] rich tapestry around Peace, the characters around him, the push and pull of his life… you get totally engulfed in the story.” The story also made space for Ejiofor to consider what it means to be grounded and rooted in a community, and to grow higher and further than anyone else around you. In the film, Rob Peace is sharper than most of his peers, and through his labour and a series of fortunate decisions, he makes his way to Yale. But even with this seemingly upward mobility, Peace always returned home, not so much because he felt indebted or weighed down by his community, but because of a desire to bring all his people with him. It’s complex, rarely trodden ground to cover. As Ejiofor says, “we didn’t make the world… but we do carry around a certain amount of responsibility for the world around us. To what degree, that’s for each of us to decide.”

Ejiofor’s work is a manifestation of this notion. As an acclaimed actor, writer and director, it would be easy for him to pull the ladder up as he goes, climbing higher and higher until he’s in the sky and out of reach – the star that he is. Instead, he’s turning back, reaching out. He wants his art to include, not to be exclusive. Each new piece he works on acts as a bridge for connection, rather than something that isolates him. He knows there are real points of relation and understanding in the work he throws himself into, in the joyous moments, the struggles and conflicts – experiences we’ve all had. And the work, as I understand it, is not just in the expression, but in the making of space for an audience to connect, to reach out for the hand that he’s extended back. It raises a question, that I, and I assume many of us, love being asked, explicitly or implicitly, when engaging with any artistic medium: “do you know this feeling?”

It’s clear this is a man who derives not just pleasure, but real joy from his work. “There’s no sudden strike when I look out of the window… the artistry is not in the clouds,” he says. “It’s labour.” Towards the end of our conversation, when I ask what he’s working on at the moment, he says, “I’m waiting.” And I understand what he means. So much of our artistic output is trying to shorten the gap which exists between what we feel and how we express it. Expression can often feel like a wrestle, a wrangle, to find the most pertinent means for that moment and, sometimes, it can feel like a rush to get it off your chest. “You don’t want to die with the music in you,” he says. But recently, he’s been waiting, circling, trying to get things right with himself before he expresses his ideas. “It’s a delicate balancing act,” he tells me, as we’re finishing, “because there’s a restless creative animal that has guided me all of my life, right from the point that I wanted to make work. I might be getting older, but it feels young and energetic. It’s still as hungry, which is great. It’s the best feeling.”

Photography Anton Gottlob

Styling Stuart Williamson

Producer Katie Beddoe

Groomer Alexis Day using Armani Beauty, Babyliss Pro and The Ouai

This article is taken from Port issue 35. To continue reading, buy the issue or subscribe here