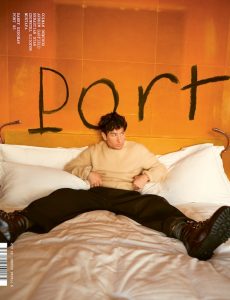

With no formal training and a career defined by taking risks, Barry Keoghan has never been one to follow the rules. Here, the Oscar-nominated actor opens up about his unique approach to his craft, why he still seeks out challenges, and how he’s finally finding a sense of calm in the chaos of Hollywood

Barry Keoghan has started brushing his teeth with his left hand. He explains the method in his madness duly: “Because I’m doing that, I have to be present. I’m not thinking about getting in the car, or getting to work, or what I’ve got to do that day, or anything else. I’m focused on brushing my teeth,” he says over the phone from the Isle of Wight, where he’s preparing for a new role, as well as the upcoming Peaky Blinders film shoot, enjoying a few days of calm before the storm.

The toothbrush anecdote is to illustrate a wider point: when he took acting classes earlier this year at the prestigious Stella Adler Academy in Los Angeles, he was intimidated by the academic, technical approach. “But not in a bad way,” he clarifies. “There were moments where I had to get up on stage, or do a scene, and I just found it really hard.” Perhaps the idea that an Oscar-nominated actor could find acting classes a tough crack sounds absurd; Keoghan himself is also sceptical. “But it was that fear I wanted to feel again. I wanted to learn, y’know? Be dropped in the deep end and see how other people do it.” While he speaks highly of the acting classes and everyone he met at the academy, his experience confirmed to Keoghan that he’s quite happy feeling his way through. Through a turbulent childhood in Dublin, he has – very much against the odds – risen to become one of the most recognisable young actors in Hollywood. And he did it all with absolutely no formal training, making him an anomaly within the heavily schooled British and Irish film industries.

“My whole thing is to come across as engaged and authentic as possible on the screen,” he explains. “I think for me, to train to do that… sometimes you’ve lost already because you’re trying. Whether it’s in boxing or acting, I’m always trying to not think so much about what’s coming next – to be instinctual. And when you’re not thinking about what comes next… the worry’s gone for a second. Maybe two seconds,” he concludes. “I think this is why I loved working with Andrea so much, she very much has that same feeling.”

This is Andrea Arnold who, for her sixth feature, Bird, cast Keoghan as Bug – a young father covered head to toe in tattoos of insects, trying to fund his upcoming wedding by selling hallucinogenic toad slime. Keoghan is the bad-but-trying dad of the film’s protagonist, Bailey, who develops a friendship with a strange outsider looking for his family. When Keoghan met Arnold in an east London fish and chip shop to discuss working together, she gave him a toffee apple. “I remember then I had to get on a plane and bring the toffee apple through customs and security, with it in the plastic tray,” he laughs. “Customs were looking at me going, ‘Are you okay?’ And I was like, ‘Am grand!’ That’s what I really remember about meeting her.”

This is not the answer one might expect when asking an actor about their first impressions of a world-renowned filmmaker. But it is a uniquely Barry Keoghan answer; he is partial to tangents, asides, and doing a bit. Perhaps it was bold of me to assume I, a person with ADHD, could have a 40-minute conversation with another person who also has ADHD without getting distracted, but we do end up having a lengthy chat about the Isle of Wight’s only cinema all the same (they’re currently showing Wonka if you were wondering). A conversation with Keoghan is less a matter of asking questions and receiving answers than it is a matter of keeping pace.

The same could be said for his acting. Over the last seven years, since his breakout role as a spaghetti-scarfing sociopath in Yorgos Lanthimos’ The Killing of a Sacred Deer, Keoghan has been cutting a bold path through the film industry, gravitating to films that utilise his charisma for nefarious purposes. Chief among them, of course, is Emerald Fennell’s Saltburn, which scandalised and tantalised Hollywood last year and saw Keoghan quite literally bare it all.

With the world at his feet and press at his door, Keoghan’s name was suddenly attached to flashy projects. He was supposed to face off against his countryman Paul Mescal in this autumn’s hotly anticipated Gladiator sequel, sending hearts a-flutter around the globe; ultimately Keoghan left the project, and signed on for Bird. When I first interviewed Keoghan, in 2018 on the press tour for Bart Layton’s American Animals, he told me then he wanted to work with Arnold. I remind him of this. “Isn’t that insane?” he laughs as though he’s surprised at his own audacity. “Isn’t that crazy?”

This dream director list (which lives in his iPhone’s notes app) has been mentioned before; he’s also ticked off working with Chloé Zhao (Marvel’s Eternals), Martin McDonagh (The Banshees of Inisherin) and Emerald Fennell, but he’s quick to say he wants to work with all of them again. He’s still keen to talk shop with Barry Jenkins, and laments that despite being at both the Cannes and Toronto Film Festivals this year, he hasn’t had chance to watch Sean Baker’s Anora yet – another one who’s on the list. Some might refer to this as “manifesting”, but it’s not just about ticking names off a wish list; Keoghan possesses an infectious enthusiasm for his craft that goes beyond name-checking cool directors.

When he lived in Los Angeles briefly, he used to ride his BMX down to Quentin Tarantino’s historic New Beverley Cinema and see whatever was showing: “I remember seeing Bullitt there,” he notes. “I saw all this amazing Japanese cinema, and they’re all on these gorgeous old prints – and sometimes the sound wouldn’t quite match up with whatever you were seeing, but God, I loved it. They were beautiful.” He laments that everyone’s always searching for a new gimmick in filmmaking. “I think the films I’m drawn to, they’re the ones that really understand a community,” he says. “That aren’t tryna be all flashy.” I agree and mention Mike Leigh – a fantastically unfussy filmmaker. “Mike Leigh!” Keoghan responds enthusiastically. “Ken Loach! Or Andrea Arnold,” he adds playfully. “I’m starting to understand the industry, y’know, after what, 11, 12 years, but it can go from one day you’re just at home and then the next day you’re on a massive movie set and you basically don’t have to do anything for yourself.” Keoghan says. “It’s quite dangerous, even though people have good intentions and want to look after you, there can suddenly be all these distractions.”

Keoghan knows this all too well. His meteoric ascent after Saltburn premiered at Telluride last year has been well-documented. Suddenly there are headlines and gossip and constant scrutiny – with those also comes the promise of financial success, and that can be appealing when you’re from a working-class background, still a minority within the film industry. “I don’t feel pressured into taking something because money is calling. I mean, you wanna have a life, and you wanna have savings, you wanna buy a house, you wanna do it all, all things like that – but…” he trails off a little, contemplative. “That can’t always be the focus. Some people want to be working all the time, and that’s fine for them. But for me, I feel like every time I work it takes a little something from me. Sometimes it’s things I don’t even know about.”

Keoghan isn’t someone who can leave it all on set at the end of the day. The intensity that is praised so widely in his performances comes from a real place; past collaborators have compared him to a wolf, a fox and a shark. “That was Emerald!” he pipes up giddily. “She said it about my eyes, but I don’t think sharks have very nice eyes, so what was she tryna say?!” Such comparisons are apt; there is something inscrutable and mesmerising about him, both on-screen and off. In Bird, he’s all smiles and sunshine until he’s very suddenly not; a volatile presence whose love for his daughter (at least initially) seems conditional on her willingness to do exactly what he tells her. But as Keoghan notes, Arnold has an innate understanding of her characters, which are built in collaboration with the actors (and often non-actors) portraying them. And while Keoghan mentions that he’s been going to therapy and is enjoying the experience, there’s still a part of him that likes to process his emotions through his work. “When I’m looking at a script, I’ve gotta think, ‘Have I played this character before? Is this giving me a challenge, or showing me a new filmmaker? Is it going to change my perspective?’” And then, he adds, “Is it worth it, physically and emotionally?”

This concern tracks with Keoghan’s tendency to be drawn to darker stories and characters, such as the sullen sheep farmer’s son Jack in Christopher Andrews’ Bring Them Down, which premiered in September at the Toronto Film Festival. The quietly brutal thriller pits Keoghan against Christopher Abbott in rural Ireland, where two families clash as a bitter longstanding feud comes to a violent head. This is par for the course for Keoghan, who has become the go-to for filmmakers with a “Freaky Little Guy” in their script but, in Bring Them Down, Keoghan’s performance is defined by its apparent normalcy, until things spin out of control. Here he’s the lamb rather than the lion; a late scene between him and co-star Aaron Heffernan is a masterclass in non-verbal performance, as visible disgust and despair slowly register on Keoghan’s face.

This visceral quality in his work and his palpable enthusiasm is what has drawn so many filmmakers to Keoghan so far. He’s recently finished shooting with Waves director Trey Edward Shults, starring alongside The Weeknd and Jenna Ortega in a buzzy project he can’t say anything about. What he can talk about, though, is his long-gestating personal project inspired by his own turbulent upbringing. “I feel like I’ve not had a chance to really pour myself into something, y’know, to really bring my own stuff forward,” he explains, “And I feel right now I can do that in a constructive way because I’ve had a lot of good therapy – now I can pick stuff out that I want to revisit, find places I want to go back to, to bring certain feelings to the surface and use them creatively.” He mentions Charlotte Wells’ Aftersun (“Fucking gorgeous movie”) as an inspiration. “In terms of the relationship, I thought it was so beautiful and so delicate. Here, it’s a young boxer on the cusp of success, as he’s fighting for full custody of his little sister, ’cause their mum’s an addict. I want to focus on that, and this idea of who and what to fight for, and what success means for an inner-city kid.”

I mention that, like Arnold or Andrews, no one knows that community better and that authenticity is rare when it comes to working-class stories. He laughs and tells me about going to Dublin to shoot a short film for Gucci’s Absolute Beginners project in 2020; he shot on black and white 16mm, hiring a first-time actor he found at a boxing gym. “He looked at me and said ‘Is this a joke? You playing a game?’ and I really had to convince him I was legit,” Keoghan recalls. “But that’s what I wanna do with my film,” he assures me. “Four-three ratio, black and white 16mm, non-professional lead,” He sounds, as ever, enthusiastic and determined. But then he adds, in Keoghan fashion: “knowing me, I’d probably leave the lens cap on for the whole thing.”

Photography Christopher Anderson

Styling Mitchell Belk

Production Art-Engine

Groomer Charley McEwen

Shot on location @45parklane

Special thanks to @circlepr

This article is taken from Port issue 35. To continue reading, buy the issue or subscribe here