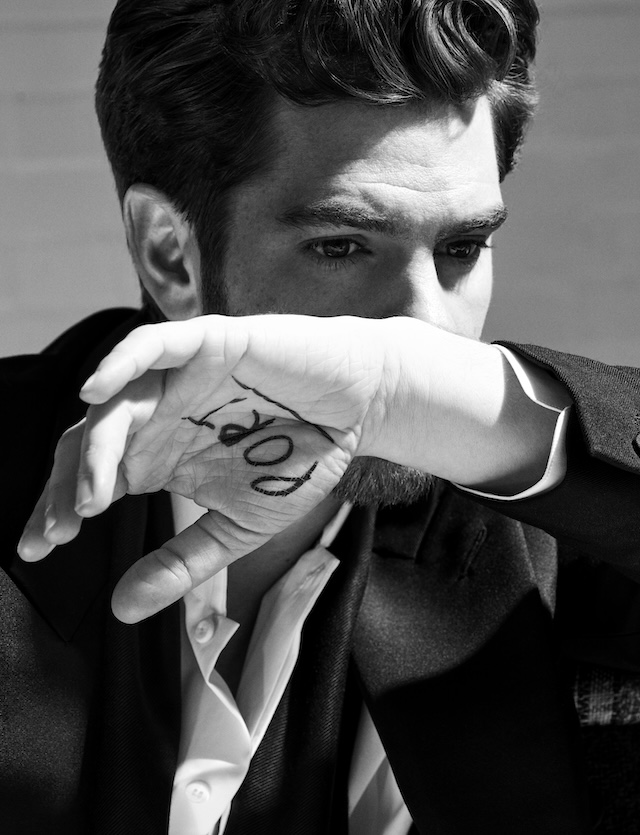

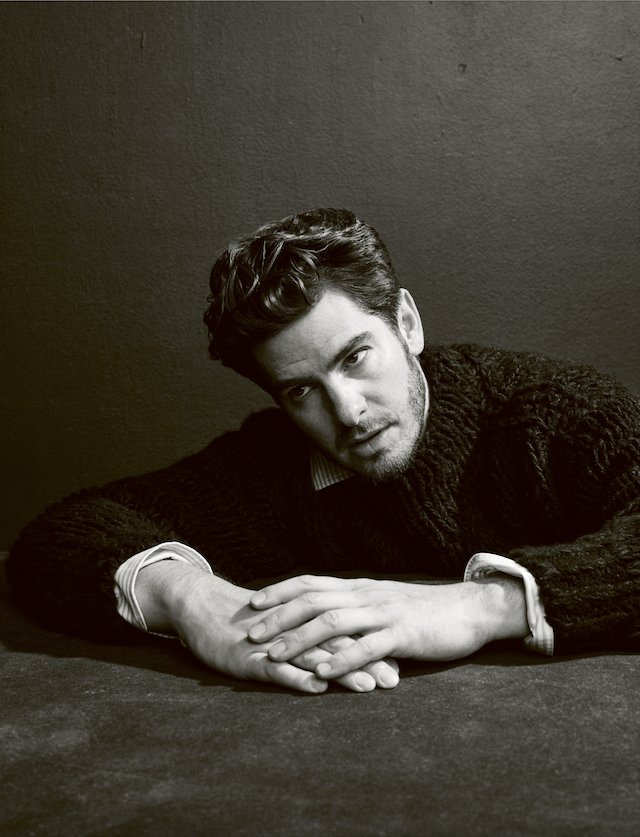

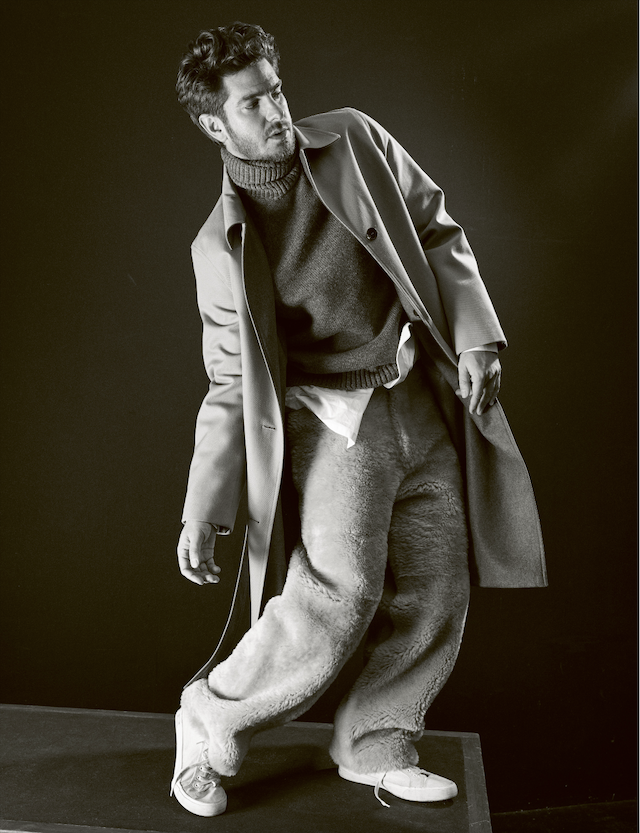

Fresh from watching his latest film, We Live In Time, Daisy Edgar-Jones is still processing the emotional impact of Garfield and Florence Pugh’s performances. In this conversation, Garfield – known for his roles in Tick, Tick… Boom! and The Amazing Spider-Man – opens up about how the film’s exploration of grief and joy parallels his own life story, and the pair discuss everything from working together on Under the Banner of Heaven to regret, loss, vulnerability, and the beauty of fleeting moments

Daisy Edgar-Jones: I’ve already texted you this, but yours and Florence’s performances were so breathtakingly beautiful. I know you hate compliments, but this film needs to be seen by as many people as possible. It’s gut-wrenching and sad, but it’s also so romantic, so full of joy. Every moment where I thought it was going to get too heavy, it brought us back into light. I think that in life, with all of the darkest moments, you also have moments of unbelievable joy and levity. You and Florence brought that in spades. I really was inconsolable.

Andrew Garfield: It’s a British sensibility, isn’t it, to try for gallows humour, but also you’ve got to laugh to keep from crying. I’m discovering this more as I age. The more I accept grief, loss, sorrow and the hard stuff, the more I feel it, the more capacity I have for joy, love and proper connection. We’re so conditioned to the opposite now because the world is so horrifically divided and scary. The future is so uncertain, it’s really hard to have an open heart. There are so many good reasons to be defensive, to be closed off, to have our hearts be really calcified, to be full of irony and to be full of unwillingness to be truly vulnerable. It’s so scary to be honest, how fragile we all are.

This film shows two people, and it represents all of us. They are everyday people; they are universally acknowledged. They are faced with the reality that there’s only one way to have a meaningful life, and it’s by having an open-heartedness to the slings and arrows of life and just accepting this is the setup, this is the way it is. There’s no circumnavigating. There’s no ascending over the top of suffering. The only way through is through, and then, in going through and down, we get to the heart of things.

DEJ: That’s so beautifully said and so true. I know that you’ve experienced grief in your life, and I have too at an early age, and I think the fullness of that feeling, that pain, like you said, does crack you open to experiencing the fullness of all emotion. It’s a gift, and it’s also painful to be able to be that open. What this story does so well is show you that, ultimately, what really matters in life are the people in it, and the moments that you share, because they’re fleeting. There’s a beautiful scene in the petrol station where you and Florence drove away in the ambulance, and it lingered on the two petrol workers, and it was just a moment in their life. But for all four of those people, it’ll be something that they have shared, that no one else will have. It’s just so beautiful, those small, little ripple effects. I love films that celebrate that and play with time in that way. I was wondering, did you film sequentially? Or was it all out of order?

AG: Because Florence had three hairdos – she had one with bangs, which was a wig, I think, and then the shaved head, and then there was one without bangs. It was as chaotic as any other film. In sequence, out of sequence, location-based, time-based. It was an eight-week shoot, so it actually felt like we had quite a lot of time to do it, relatively speaking. But the writing was so great, and Florence is so good that, with those two things, you know where you are at all times.

How great is it when you get to completely tune in to your scene partner and feel like you’re on a ride together and you’re supporting each other. Occasionally we don’t get that, but when we do, it’s the most beautiful. Even hard scenes become really pleasurable.

DEJ: It’s like singing together. How did you find your chemistry with Florence? Did you rehearse a lot together?

AG: I love working with Florence, because she’s very spontaneous and alive; she wants to be surprised, and she wants to surprise. She’s courageous in that way. When we both acknowledged that in each other, we could really let go every single time.

We didn’t do a chemistry read, and I think we were both really nervous. Having read the script, we realised the film was going to require some nakedness – emotionally, physically, literally and spiritually. I don’t know about you, but I think I can speak for her and me in the sense that I think safety is paramount – when you’re like, ‘oh, I can really be vulnerable here’, and I’m not going to be judged, and I can make mistakes and I’m not going to judge that person. I want to create a work environment where there is no failure, where it’s a playpen. I spoke to John, the director, about that very early on; we had worked together before on the second film I made, called Boy A for Channel 4. But I’m a very different person on set now, and I’m a very different actor. The same, but hopefully a bit more expanded and competent.

DEJ: What was it that drew you to this first and foremost, was it the Florence element? Was it the script? Was it working again with John?

AG: I was on a sabbatical. After we worked together for Under the Banner of Heaven, and I had to promote Tick, Tick… Boom! and The Amazing Spider-Man, I was just a bit tired. After mum had died, I was also very reflective. I lost some of my mojo, or some of my drive and desire.

It was just a really interesting, mysterious shift that happened in my body that was just unexpected. I didn’t know what mattered anymore or where I was supposed to be. In those moments, the hardest thing to do is to wait, be still and to not try to rush and fill the time with stuff that will distract from rest or being present with people. I really tried to slow down and be quiet, process and just be a person. And, of course, it’s a privilege and very lucky. I wasn’t necessarily intentionally taking two-and-a-bit years off, but then a year into that break from acting, this script came, and it felt like I’d been waiting for it. It was all the themes that I had been sitting with for a year. About time, ageing, middle age, loss, the deepest longings that are kind of inborn in us, and what matters. It’s a film that asks what matters and where we want to put our time, where we want to put our energy.

Now that I’m 41, I’m able to feel that so much more acutely. I’m looking back and I’m looking forward to where I’m at. The film is just part of my sabbatical. This is part of my break. This doesn’t feel like work. This feels like I get to go and put all of the work I’m doing in my own life into art. How much better does it get? I don’t think it gets much better for an artist than to feel like you’re making something personal.

DEJ: It’s interesting that time is something that you’re curious about in both the art you consume and then the work you connect with and want to make. It is for me too. Maybe it’s in part because with what we do, we’re so presented with fate, or we are an agent of our own fate, in that you could have chosen not to do this job. Then you wouldn’t have had that moment with Florence and realised that you have this amazing dynamic with each other that you’ll hopefully play with again. You might not have learned or healed through this in the way that you did. If you could turn back time, would you?

AG: Fuck, that’s such a good question, Daisy.

DEJ: Thanks.

AG: I think we’ve seen enough time travel films to realise that it’s a bad idea, ultimately. But it might be tempting.

DEJ: Is there anything in particular you would redo or change?

AG: Girl, coming in with the hard ball. But existential questions are my thing. Whenever I start pulling on that thread, I quickly realise there’s nothing I would change. If it could have been different, it would have been. I think about regret sometimes, and I think it can be really guiding and healing. If you have a regret about something that you could have done differently or that you know you’ll have an opportunity to do in a different way in the future, it can change behaviour. I think that regret is a beautiful gift. I don’t think I could go back and change anything. Hopefully we get another go around. I’m praying that reincarnation is a real thing.

DEJ: I think I use my work as an ability to feel things, because I’m too scared to feel them myself. I use characters as a way to voice or sink into that feeling whilst always knowing there’s a disconnect. Do you find the opposite?

AG: I feel like our work has the potential to be healing for us as individuals, and therefore for an audience. It’s like that wounded healer thing. A therapist is only a great therapist if they’re also getting therapy, if they’re bringing their own woundedness. The beauty of actors, or the job description of an actor, is that we get to be the wounded healers. We get to be the ones that dig into the wounds of humanity, the universal things that bind us. I feel like it’s a vehicle to connect to self, to audience and to proper community.

DEJ: Whenever I get asked the question of whether the experience of fame is overwhelming, I always say that it’s your attitude to it. I learned that from you, because I remember meeting you in a really formative time in my life. I think I was 22 when we met, I’d been away from home for a whole year and I’d just been launched during COVID. I was very unsure of the world, really, and what it meant to be moving into a space I wasn’t used to. I remember you hopping on an electric scooter and scooting around Calgary and just being yourself. I remember people being like, ‘Is that Spider-Man?’ And you just kept scooting. I learned so much from observing you do that. You were being completely normal, lovely, fun and light and never making it a thing. You just had far more control over it. I remember being really moved by that.

AG: Thank you for sharing that. I’m in a constant process with that, and I can go all over the map with my relationship to being a recognisable face in public. I’m so imperfect with it, and I really struggle with it a lot still. It’s hard to trust people in certain ways because of it, and it’s hard to really connect again. You see it happening more and more now with certain people that I’m inspired by as well, where there’s a real honouring of our ordinariness. I’m going to make sure that I don’t over-identify with a false image, or how people treat me, because they don’t actually know me. And if they got to know me, it would be very, very different. To not over identify with looking stunning and made up on a red carpet, and having people you know respond in whatever way they’re responding is a silly, fun thing. Then there’s an inevitable crash and drop in energy, back into ordinariness. I have to work really hard to keep that connection with myself, because otherwise it’s a soul sickness.

DEJ: That’s the beauty of the film that you just made, because it sits in the profundity of the domestic, like the simple cracking of an egg. Moments that actually matter.

AG: [Florence is] doing something so ordinary, but in that moment, it’s like I’m watching the goddess of the cosmos moving planets around, playing with planets. That’s what I’m seeing. I think about Simone Biles and Chappell Roan setting boundaries with the world and a toxic culture that wants to harvest and suck out all of your life force for the benefit of commodification. It’s been going on, obviously, for decades, since the Golden Age of Hollywood and before. But now more than ever, we have to respond like warriors and put guards at the gates to retain our souls, the simplicity of our lives, and live the way we want to live. That benefits everyone.

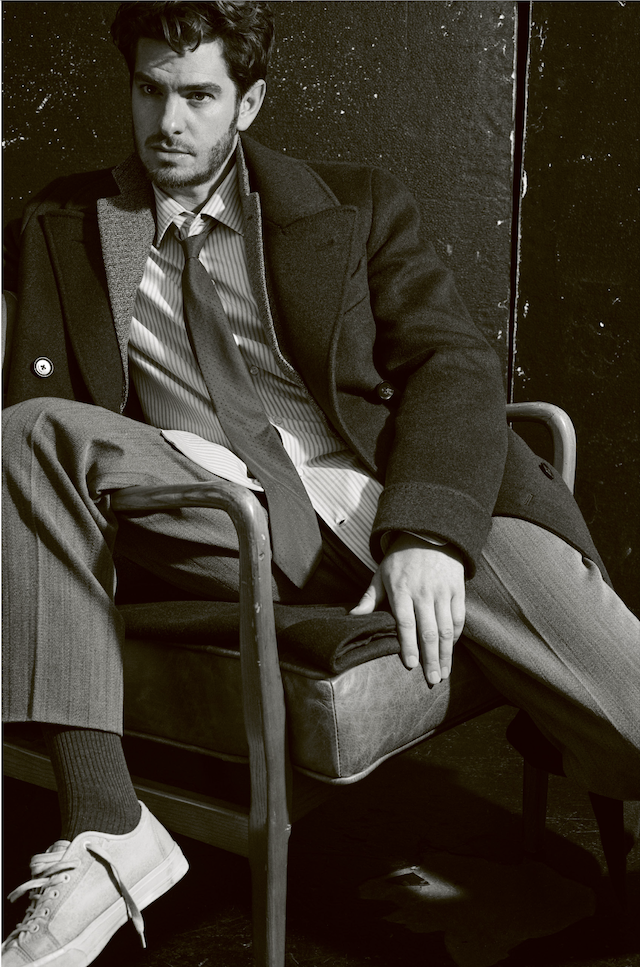

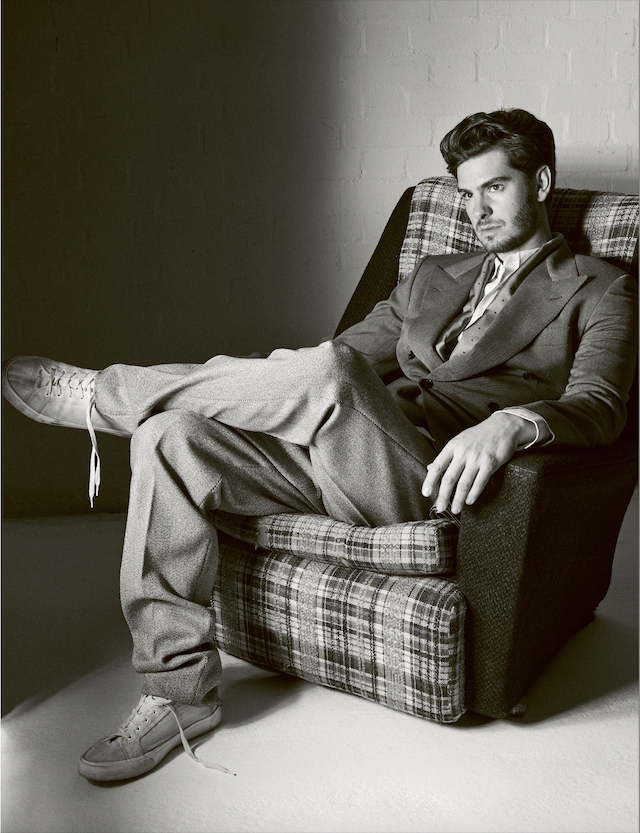

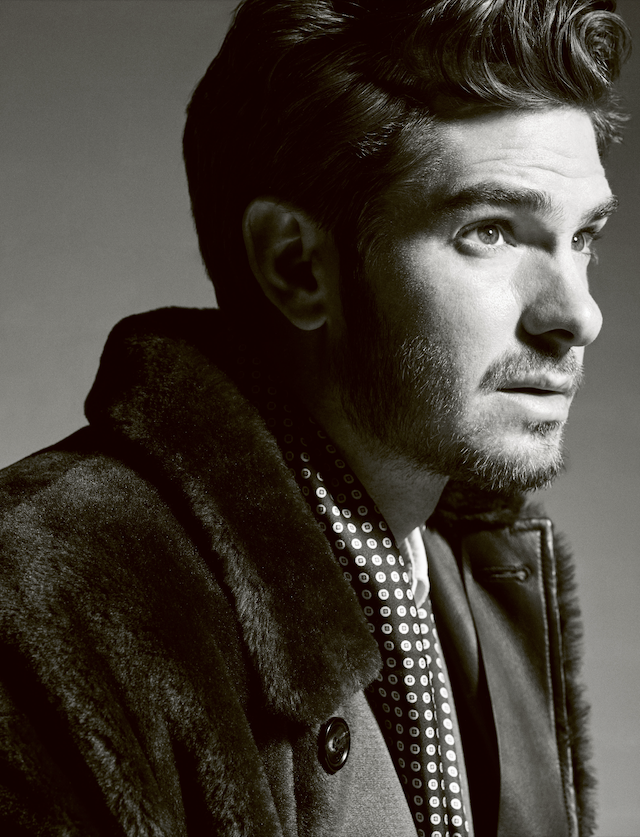

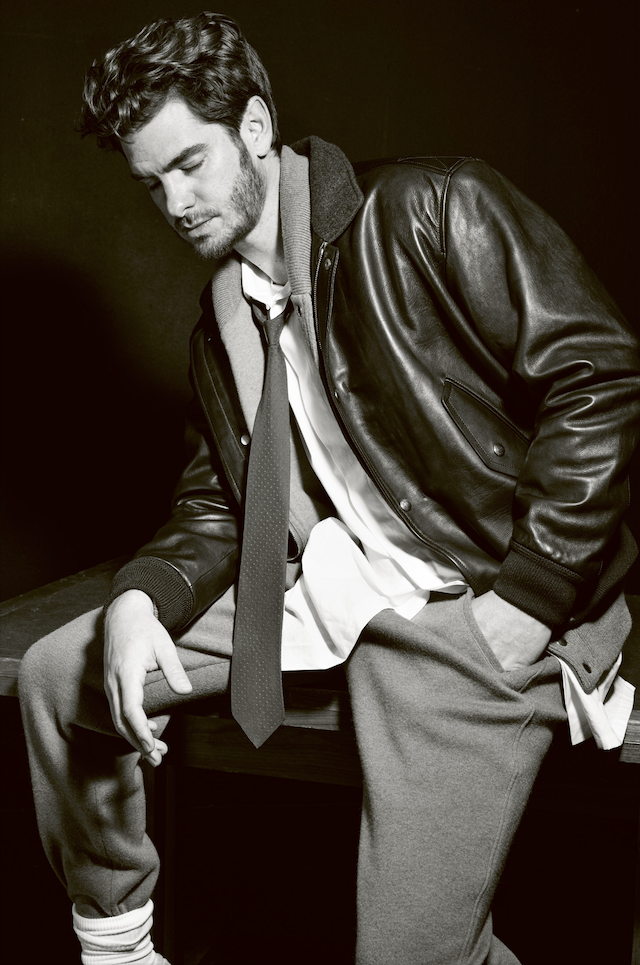

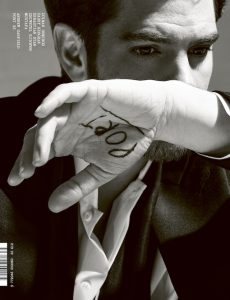

Photography Liz Collins

Styling Naomi Miller

Production The Production Factory

Groomer Emma Day at The Wall Group using Officine Universelle Buly 1803

This article is taken from Port issue 35. To continue reading, buy the issue or subscribe here