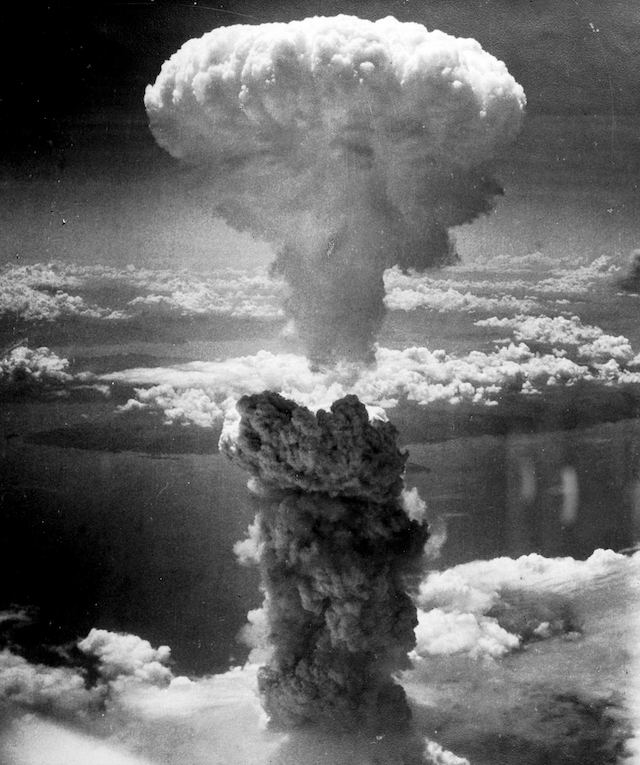

Seventy-six years after the bombing of Nagasaki and Hiroshima, John Harris Dunning investigates the birth of a monstrous legacy

“We knew the world would not be the same. A few people laughed, a few people cried, most people were silent. I remembered the line from the Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad-Gita. Vishnu is trying to persuade the Prince that he should do his duty and to impress him takes on his multi-armed form and says, ‘Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.’ I suppose we all thought that, one way or another.”

– Robert Oppenheimer, father of the atomic bomb

Rain lashes a Japanese village at night. A man stands in a doorway, probing the darkness for the source of a pounding that cuts through the howling wind. His face suddenly contorts in terror and he stumbles back into the interior, throwing himself over his wife as the walls collapse in on them. A giant scaly shape lumbers past. . . And so audiences caught their first glimpse of Godzilla, king of the monsters. Released in 1954, Godzilla spawned the kaiju film, a genre that enjoys global popularity to this day. Kaiju can be translated from Japanese as ‘strange beast’, an accurate description of Godzilla. Although generally referred to as ‘he’, Godzilla’s creators were careful to avoid specifying the creature’s sex. The name has its roots in the words gorira (gorilla) and kujira (whale). Godzilla seemed to burst fully formed from the anxieties surrounding the birth of the atomic age. Japan was still reeling from the recent bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and its subsequent defeat. Its domestic film industry was operating at a fraction of its normal capacity, its cinemas glutted with American product. This cross-pollination with Hollywood was to become an important ingredient of the kaiju film. A hugely successful rerelease of the 1933 version of King Kong put giant monsters at the forefront of the Japanese popular imagination. The forgettable B-grade monster flick The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms (1953) – which bears unmistakable parallels to Godzilla – further supplied the blueprint for the kaiju phenomenon.

But if science fiction gave this Frankenstein’s monster flesh, then actual events brought it to life; in early 1954 Japanese-American diplomatic relationships were brought to boiling point by America’s flagrantly irresponsible nuclear testing in the Pacific Bikini Atoll. The crew of the Japanese tuna trawler Lucky Dragon was exposed to deadly radiation, despite earlier American assurances that they would be well within the safety zone. This event is clearly echoed in the first scenes of Godzilla, when deep-sea explosions herald the coming of the king of monsters. Coming only two years after the end of the American occupation, when open criticism of America in the media was virtually impossible, this thinly veiled portrayal of the incident was clearly recognised by audiences. Godzilla’s city-flattening antics – so reminiscent of the American annihilation of Nagasaki and Hiroshima – also allowed for an otherwise impossible cathartic release.

Godzilla – and the innumerable kaiju who followed in its huge footsteps – will always be linked to the dawn of the atomic age and related ecological concerns. But like all truly powerful mythologies, the figure of the kaiju resists any easy reading. This quintessentially modern pop-culture icon also has roots reaching back millennia. The Japanese have a long tradition of fantastical beasts and monsters, many of which can be traced back to the influential 4th-century Chinese text Classic of Mountains and Seas. Like Godzilla and other kaiju, the classic dragon can traditionally be both benevolent and malevolent – and also has a strong connection to ecology and the wellbeing of the planet. The islands that constitute Japan sit at the juncture of three overlapping tectonic plates, making it the most volcanically unstable nation on Earth. Overwhelming natural catastrophes are part of the natural consciousness. The very creation myth of Japan tells of goddess Izanami, co-creator of the archipelago of Japan, dying while giving birth to her child Ho-musubi, causer of fire.

Godzilla – and many of the kaiju – are not malevolent by intent. The damage they do humanity and its cities is mostly unintentional; they are simply not important enough to warrant the monsters’ attention. The kaiju genre shares this characteristic with the work of influential American writer HP Lovecraft, whose work set the blueprint for contemporary horror; his story cycle centres on an immense cosmic monster Cthulhu, who, significantly, also slumbers in the depths of the ocean until the unwise actions of humanity awaken it, effectively ending man’s dominion over the earth. Both Lovecraft and the kaiju genre operate at the intersection of horror and science fiction, presenting a universe in which man plays an insignificant role. This very postmodern view can be perceived as terrifying, but it’s also a kind of antidote to a relentlessly human-centric worldview, and chimed nicely with the increasing understanding of ecological issues in the 20th century.

After the huge success of Godzilla, the formula was quickly copied, and a host of kaiju fluttered, slithered and crawled across the big screen. Monsters like Mothra, Gamera and Rodan were so popular that they spawned franchises of their own. By 1967 each of the five major studios in Japan had at least one kaiju film, kick-starting the domestic film industry’s recovery. These films were then exported to America where they earned big box office. Badly edited, with cheaply shot footage inserted to appeal to the Western audiences, for decades they were critically ignored and labelled camp or B-grade. They’ve been re-evaluated in recent years as restored versions have been made available in English and other European languages. Ongoing franchises like Cloverfield, Pacific Rim and the Legendary MonsterVerse films like Kong: Skull Island and the upcoming Godzilla vs. Kong make it clear that the kaiju genre is alive and well, and still wreaking havoc across the globe.

This article is taken from issue 27. To buy the issue or subscribe, click here