After a decade of pop-ups, husband-and-wife duo John and Desiree Chantarasak opened their first permanent restaurant in late 2024 – a 44-cover space in Marylebone that earned a Michelin star within three months. Here, John speaks about balancing Thai and British ingredients, the power of patience, and how the kitchen became a reflection of his dual heritage

Supper begins with a single bite of Comice pear, candied beetroot and roasted Suffolk rapeseed. Cool, sharp, sweet and nutty, slowly oozing its flavour across the tongue. The beetroot, cooked down into something sticky and almost jam-like, tastes earthy and just a touch fermented, while the pear cleanses and lifts the palette in preparation for the next dish: the winter radish cake. When plated, it looks humble, though it is anything but. A crisp golden crust gives way to a tender, almost gelatinous centre – dense yet silky, like a savoury mochi with a vegetal heart. The cake carries the umami of fermented daikon, grounded, slightly tart and a little funky, layered with house-made vegetable treacle and a herby snap of tarragon. There’s also a side dish of whole grain farro that’s smoked and peppered, flecked with laab spice. A winter salad dressed in Black Bee Honey and salted duck egg complements the table with a sense of richness, the honey lingering at the back of the throat. Then, for me – a very well catered-for vegetarian – the Lion’s Mane mushroom is the standout. Thick as a steak and as spongy as a dessert, this course is pan-fried and basted in butter before being soaked in wild garlic. It’s then dusted in puffed ancient grains, Scottish seaweed and toasted seeds – a nod to Thai furikake – and paired with a satay made from roasted British sunflower seeds and freshly pressed coconut cream.

These are some memorable moments from the winter tasting menu at AngloThai, the debut restaurant from husband-and-wife duo John and Desiree Chantarasak. Opened in November 2024 after nearly a decade of pop-ups and residencies, their 44-cover space on Seymour Place was awarded a Michelin star just three months later. With a seasonal and local menu, the restaurant brings together the flavours of Thai cuisine with British ingredients – a pairing shaped by John’s own heritage, with a Thai father and British mother, and years of cooking experience in both Bangkok and London. Rice doesn’t grow in the UK, so instead they use ancient grains like naked oats and spelt. Tamarind and lime are swapped with foraged sea buckthorn berries. Holy basil is grown hydroponically in east London. Chillies and honey are sourced from the UK. Even the outer leaves of cabbage are pressed to replace banana leaves. In this conversation which took place not long after the restaurant opened its doors, John speaks about his long-burning vision, the relationship between British and Thai ingredients, the evolution of his signature dishes, and the small daily improvements that earned this culinary star.

Congrats on the opening. How have things progressed since then?

I think it’s gone well. It’s generally gone to plan. I’ve been involved in a few restaurant openings before – not my own – but I took a lot from those experiences. We had a big build-up, so we had time to think and gestate about what we wanted to achieve. We went into it with the right mentality, setting ourselves up for success, and tried to make it as smooth as possible. So far, it’s been smooth.

I’ve been cooking a version of this concept for over nine years now. The catalyst to open a restaurant started about four years ago with my wife – we began approaching landlords, speaking to agents, and trying to figure out the process. We were probably a bit naive about it, and originally, the idea was on a smaller scale than what it’s become.

We’ve been plugging away with pop-ups all over – London, Jersey, Edinburgh even further afield – and tried to grow the brand organically. That slow burner approach is frustrating and tiring, but the organic following it built has been amazing. People are coming in saying, “I came to your pop-up two years ago”. That’s incredible – that they still care, that they believed we’d open one day and now want to see it for themselves.

The slow pace clearly paid off. There’s a real appreciation for time in everything you’ve built – does that sense of pace filter into the restaurant experience too?

Definitely. Time has been our friend in this. Watching everything come together – the wood treatments, design, the music – after pouring blood, sweat and tears into it for so long, we really feel like people notice that. It’s more than just the food being good or the wine list being nice. Diners sit down and say, “Wow, you’ve thought about everything”. That was always the goal.

We didn’t want it to be just a place to eat food. It’s an experiential style of dining. Even the interiors are part of that. There’s a nod to Thai Art Deco, but we also worked with independent Thai craftspeople who are revolutionising design back home. It’s a modern approach, with deep respect for what came before. That’s the whole idea behind AngloThai; it can feel at home in London, Bangkok, New York, Barcelona. It’s a modern interpretation of Thailand.

It’s interesting how that modern Thai identity runs through both the food and the interiors.

It’s our chance to share more than food – we’re talking about culture. My wife and I have travelled around Thailand, scratching away at those layers, and we worked really closely with our designer May Redding, who’s now a close friend. She’s half American, half Thai, born and raised in Thailand. She understands what’s kitsch or cliché in restaurant design, and what feels respectful and contemporary.

We weren’t trying to make something “thematic”. We wanted to work with craftspeople pushing their fields forward. Like the seats – people sit down and say, “These are like nothing I’ve seen in the UK”. They were made by a company called Moonler in Chiang Mai. It was a mission to get them here, but worth it. It’s all about that feeling of a well-loved home, with order to the chaos. We didn’t want uniformity. One size tables, all the same colour – you end up with a canteen. We wanted individuality and a sense of home.

Has cooking always been part of your life? Was it always the plan?

I was fortunate. I grew up in a household where home-cooked meals were the norm. My mum made everything from scratch. We had vegetable patches, baked our own bread. I do the same with my kids now – my son’s three, and he’s involved in the kitchen already. It’s just what we do.

But I came to cooking late. I retrained about 12 years ago. Before that, I was into music, living in London, doing gigs and day jobs. Then I moved to Bangkok, trained at Le Cordon Bleu and studied the classical French diploma. Towards the end, they started to integrate local Thai ingredients, so it was this fusion of French technique and Thai produce.

After graduating, I interned at a restaurant called nahm. When it moved from London to Bangkok, it became a huge deal and won a Michelin star, got into the World’s 50 Best. That experience was a mind-meld. I thought I knew a lot from my training, but being in that kitchen opened my eyes.

Was it at nahm that you knew you wanted to cook Thai food?

Yeah. I came back to the UK after two years and connected with Andy Oliver, who was opening Som Saa as a pop-up in Climpson’s Arch, where Brat is now. It was a rapid, exponential journey; training in Thailand, then straight into something that became a huge hit. It exposed London to a different style of Thai food. I was hooked.

I stayed at Som Saa for five years. Left at the end of 2018, and from then on, it’s been the journey to AngloThai.

How did you and your wife meet – and how do you work together?

She came to Som Saa during the early days at Climpson’s Arch. She tagged along to a friend’s date night. We saw each other, exchanged numbers, went on a date the next week and never looked back.

She understood what I was trying to do. I retrained and moved my whole life to go to Bangkok. When I came back, I was sleeping on my cousin’s floor, working on pop-ups. She never questioned the chef lifestyle. Her support was unwavering.

She was a graphic designer for Amazon when we met, but she started moonlighting in wine bars, studied WSET wine qualifications, and eventually transitioned into hospitality. During COVID, she was made redundant, and that became the sign. We decided to go for it and fully commit to opening a restaurant. She now does our wine list.

Are there any challenges working with your partner?

It’s a lifestyle. We talk about the restaurant 80% of the time. Our relationship was built on dinners out, wine bars, travelling for food. I don’t really have many interests outside food and drink, so it doesn’t feel like a job.

Of course it’s hard work – I was butchering three hoggets yesterday for six hours – I still enjoy it. And now, with kids, we’ve got a better sense of balance. I take Sundays off to play Lego and hang at the playground.

Let’s talk about ingredients. AngloThai is a blend of British and Thai, how do you source, and how do you keep it authentic?

To me, it is authentic, because it’s about my dual heritage. If you’re opening in central London, most of your diners are Western, and you have to acknowledge that. We’re very produce-driven. We work closely with a few trusted suppliers. One butcher covers a lot – we’ve had a ten-year relationship, so we get their best cuts. They even helped us source sheep from my wife’s family farm – non-commercial, just 20 a year, but incredible quality.

We’ve replaced palm sugar with a specific honey from Black Bee Honey near Glastonbury. It has this intense flavour, like artisanal Thai palm sugar, but it’s local. Same for grains – we removed rice from the menu two years ago. We don’t grow rice in the UK, so we use naked oats, spelt and ancient grains. We’re probably the only Asian restaurant in London that doesn’t serve rice.

What do guests say about that?

Some don’t get it – they miss the rice. But we’re telling a different story. It’s still curry and rice… just not literally. We work with farms who’ll grow for us now. We’re trying to build sustainability into the supply chain and invest in growing specific things locally.

Chillies are a good example – they grow here, but only in summer. So we dehydrate them, use dried versions for winter curries like massaman or penang. Fresh green chillies return in spring. That seasonality guides the menu.

What are some key dishes on the menu right now?

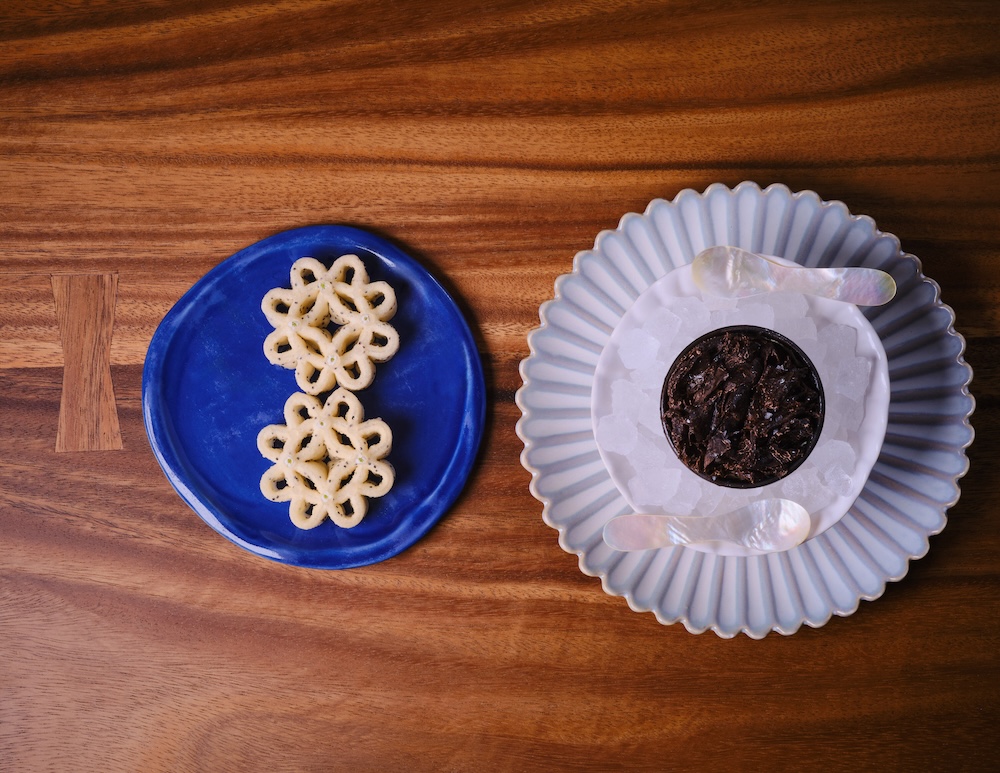

There’s a snack called ma hor, traditionally a royal Thai dish: pineapple with candied pork or prawn, and toasted peanuts. We do a vegan version on pear, with candied beetroot, British pumpkin seeds and raw rapeseed. It’s sweet, salty, nutty, balanced and the fruit refreshes the palate.

We have a really nice Lion’s Mane mushroom dish which is good for your brain but also very delicious. It’s like a big sponge, essentially. We cut it into portions, pan fry it, baste it in butter. We glaze it in vegetable treacle we make from scraps, then coat it in a kind of furikake mix – puffed grains like quinoa and millet, different kinds of spices, seeds and Scottish seaweed. It comes with a pickled mushroom purée and a satay-style sauce that we pour table side, made from roasted British sunflower seeds and fresh coconut cream.

That sounds incredible. And dessert?

I spent a lot of time in the pastry section because it was my weakest for a long time, so before opening I did pop-ups in Europe just focusing on desserts. Now we have two I love. One is based on sangkaya fak thong – Thai pumpkin custard. We make a brown butter honey cake with pumpkin puree, roasted pumpkin seed ice cream, and thin shavings of pumpkin soaked in syrup with elderflower vinegar. It tastes a bit like mango. Then there’s a duck egg coconut cream custard.

We never want to lose sight of the fact you’re in a restaurant – you just want delicious food.

Is there anything you want to add about what’s next?

We’re taking it day by day. I ask the team to come in each shift thinking about one thing they can do 1% better than last time. Do that every day for a year – you’re 365% better. We’re building something that, hopefully, lasts.