Borowczyk specialist and BFI curator Daniel Bird tells us about his ‘cinematic litmus test’ prior to the Polish director’s Kinoteka retrospective

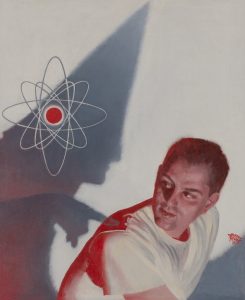

Everybody has their cinematic litmus tests, those films which you screen for people in order to gauge their response. Mine is The Theatre of Mr and Mrs Kabal. It was the first feature by the painter, sculptor and filmmaker Walerian Borowczyk. To describe it as ‘animated’ risks giving the wrong impression. Whilst The Theatre of Mr and Mrs Kabal features live-action, not to mention clips from Corps Profond (a 1963 documentary in which the inside of a living body is filmed using micro-photography), it is no Mary Poppins. Nevertheless, like all of Borowczyk’s films, it is most definitely animated in the deep sense of the word – I cannot think of a film that is more lively and ‘excited’.Visually, The Theatre of Mr and Mrs Kabal is sparse, much of it taking place in a barren, desert-like place. Graphically, it is like the flora and fauna have been scratched into the cinema screen with a blunt fork. In a world purged of colour, flashes of blue, yellow and (more often than not) red appear startling and, ultimately, poetic. Perspective is done away with, not so much like in a children’s drawing, but a martian imagining how humans see. There is, however, nothing crude about Borowczyk’s animation: his feeling for comic timing is not so much Tex Avery as Buster Keaton. When it comes to replacing images with sounds (and vice versa), he is as subtly brilliant as Robert Bresson.

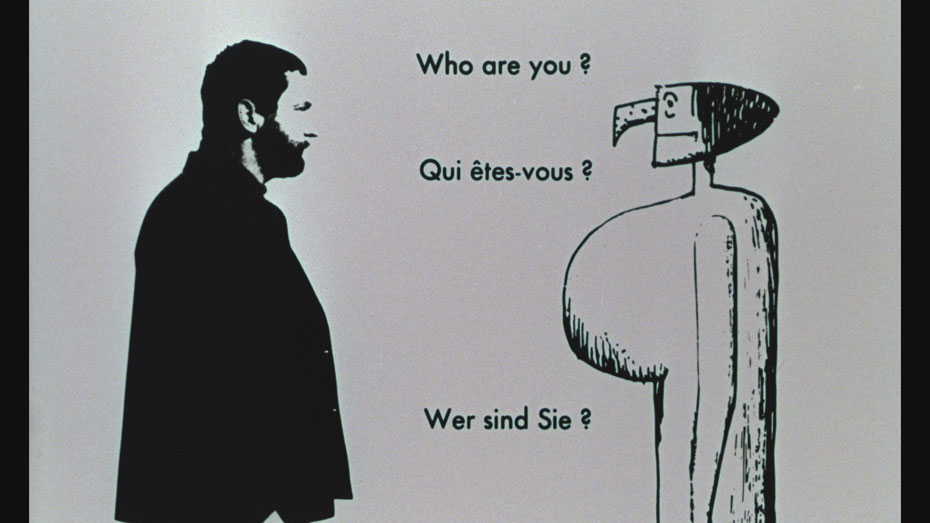

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of The Theatre of Mr and Mrs Kabal is its apparent lack of narrative. Instead of a conventional plot, Borowczyk presents us (as the title implies) ‘scenes from the life’ of Mr and Mrs Kabal. The filmmaker even makes an appearance at the beginning of the film pleading with Mrs Kabal just ‘to be’ for the sake of the paying audience. Scenes in the life of Mr and Mrs Kabal play out like demented, absurd slapstick. Mrs Kabal is tall, imposing, with a huge bust and a mechanical body. Conversely, Mr Kabal is short, rotund, and prone to spying on passive, glamorous young women through a pair of coveted binoculars. Mr Kabal infuriates Mrs Kabal, while Mrs Kabal terrifies Mr Kabal. Nevertheless, one cannot imagine one without the other.

From the outset, Borowczyk makes clear that this is an animated film ‘for adults’. Like an iceberg, lurking under the slapstick is a brutal, violent existentialism. In France, critics drew parallels between Borowczyk’s ‘absurd’ animations and the dramas of Beckett and Ionesco.My favourite scene in the film is when Mrs Kabal has butterflies in her stomach. Inspired by Corps Profond, Mr Kabal removes his wife’s head, ‘blows up’ her body, and goes inside her in pursuit of the insects. It sounds grotesque on paper, but I assure you that the sequence is bizarrely touching.

Borowczyk laboured on The Theatre of Mr and Mrs Kabal for two and half years. At the beginning of the film, Borowczyk substitutes himself with Mr Kabal. I guess that makes The Theatre of Mr and Mrs Kabal his most ‘autobiographical’ film. There is a compulsive aspect to the film, like it had to be rendered on paper under the camera at all costs.

The Theatre of Mr and Mrs Kabal is not a film for everyone, but it is the film for me.

Kinoteka, the 12th Annual Polish Film Festival runs until 30 May. Walerian Borowczyk Retrospective – Cinema of Desire, curated by Daniel Bird, starts 1 May at the BFI Southbank, and the exhibition Walerian Borowczyk: The Listening Eye takes place at the ICA from 20 May-29 June. Click for details