Dante’s Legacy in Federico Fellini’s La Dolce Vita

Among the limited celebrations of 2021 came the 700th anniversary of Dante Alighieri’s death. The poet marked his everlasting legacy within literature and Italian cultural identity so thoroughly with his creation of the Divina Commedia that his prose echoes even today. It is not hard to divine a connection between Dante’s Infernal landscapes and our world in the past few years, yet artists have been calling upon the poet’s legacy for centuries in the refinement of their art. One such artist is director Federico Fellini, and one such art piece is his 1960 film, La Dolce Vita. Set during a time of unprecedented socio-cultural change, Fellini extends a voyeuristic gaze towards this moment of historic propulsion, capturing the essence of Roman identity as it began to shed its intrinsic connection with tradition. Naturally, Fellini investigates the frenzied corrosion of Italian culture through the lens of Inferno: itself a part of Italian tradition and a thorough critique of the same theme, only centuries before.

The most immediate parallel drawn from the Divina Commedia in Fellini’s film is the utilisation of episodes within the narrative, each separate but revelatory of new sin. In his epic, Dante structures both his descent to hell and ascent to the heavens so as to follow a divinely symmetric law. Not only is the overall structure precisely calculated, but each circle found in Inferno is crafted to contain an exact balance between sin and punishment, as well as an arithmetic layering of offenses so that the more innocuous sins of the flesh have levity when opposed to the sins of the mind.

This adherence to structure and reason is lost in La Dolce Vita. Where Dante marries theology with scientific precision, Fellini divorces his film’s prose from the rules of continuity. The episodic narrative of La Dolce Vita works to dissolve the notion of continuous plot: the audience follows Marcello, our protagonist, as Marcello follows the story. Fellini constantly creates set-ups with no payoffs, engaging in a total decomposition of Marcello’s personhood. By abandoning Dante’s arithmetic divinity, Marcello is left directionless; he is lost to the whims of the city, led astray from the path to salvation because it never even existed. The warping of Dante’s structural poetry leads to Fellini’s commentary on Marcello – therefore the Italian people – losing his way, distanced from God.

In fact, the question of God’s proximity to characters is a theme that is essential to both works. In the Divina Commedia, God’s presence is irrefutable. Catholic sentiment is the driving force of the epic, with Dante as sinner who must purge himself of his faults and arrive to heaven. Like Dante, Fellini analyses the nature of Italy as a country intrinsically tied to its religious history, also believing that very history to be in process of total dissolution.

The presence of Catholicism and the people’s disrespect of it is a motif that appears throughout La Dolce Vita, usually with an irony so strong that you can feel Fellini smirking behind the screen. Yet, there is one instance where this levity is contradicted, and that is in the episode where two children claim to have seen the Madonna. Hundreds of people gather to witness the news, and reporters attempt to capture every moment. Suddenly, a torrential rain begins to fall, and total chaos ensues. In this scene, Fellini evokes the darkness of the third circle of hell – that of the gluttonous – who live among the mud and the rain. The crowds pretend to have gathered to quench their need for spiritual guidance, but truly they are hungry for the story’s sensationalism. This punishment of the crowds is the only moment when we feel God truly present in the film. Before, Fellini was amused by the new direction of Catholic sentiment in Italy, but now he chooses to severely punctuate how far Rome has fallen. Fellini’s infernal rain seems to exist only to dispel the notion that Italy has killed its God – in reality, it has only made Him angry.

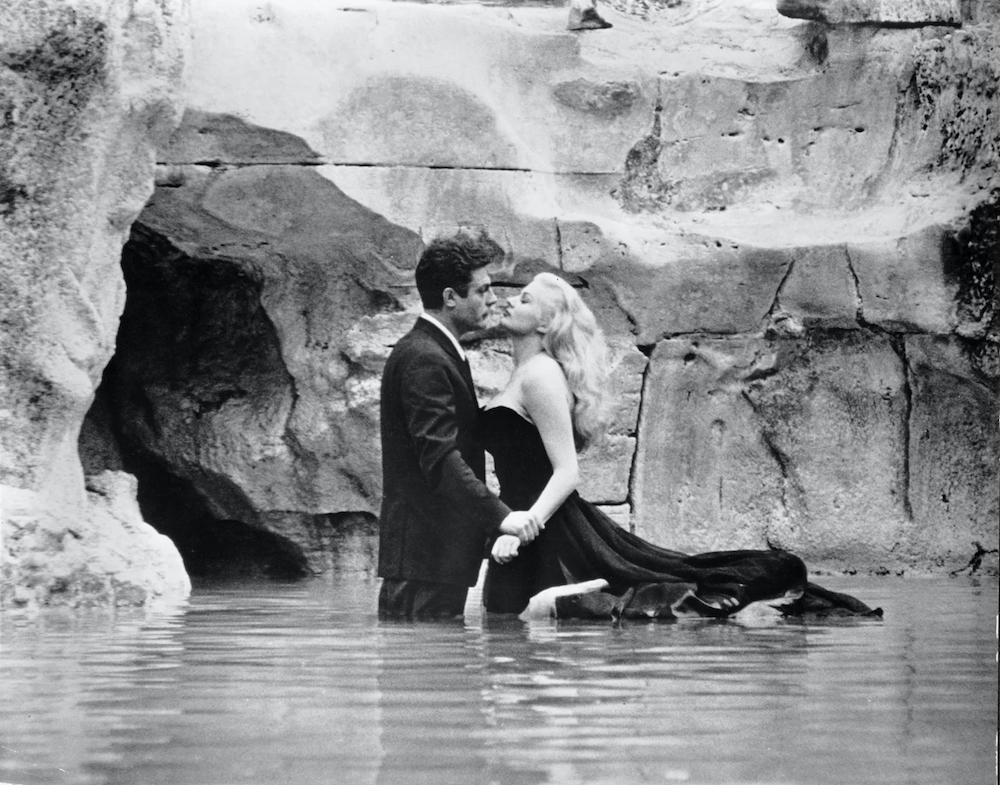

With Dante’s preoccupation with damnation came his philosophy of salvation. In simple terms, the poet attributes his ascension to intellect (the choice of writing the Divina Commedia and his master-guide Virgil), and divine femininity (his love Beatrice, awaiting him in heaven). In La Dolce Vita, Marcello encounters emblems of similar possibilities. The first is Steiner, an erudite of Roman society who encourages Marcello to pursue his literary aspirations, and his intellectual circle of friends. Yet, they themselves have been corrupted by the modern Italian scene, and their story ends in tragedy. The second is refracted into the many women who come into Marcello’s life, each spinning him further away from salvation. The true Beatrice figure is a young waitress from Umbria whom Marcello sees again at the end of the film. However, there is a sense of disinterest regarding her character. Fellini is not interested in pure morality; it does not hold a candle to the escapade with actress Sylvia, an evening exuding such internal divinity that it becomes blasphemous. For Fellini, it is impossible to find salvation when all has been corrupted, and why would you want to?

As has been the case since its creation, the Divina Commedia lends itself to the refinement of another artist’s work. Fellini casts Rome as a city in complete moral disarray, warping its own identity through its sensationalist need for all that glitters, elevating Dante’s Infernal landscapes onto the mortal realm. However – unlike Dante – Fellini refuses to critique that which he captures. Instead, he revels in his own delicious contradictions, finding life in destruction. Italy is lost and in complete disarray, but it is also sweet, it is also beautiful. In our own modern time of unprecedented change, taking the hellish prose of Dante to find and create meaning seems only natural. The question remains: must we adhere to Dante’s severity, or should we appreciate the nihilistic irony of it all?