QASIMI partners with Palestinian multi-media artists Basel Abbas & Ruanne Abou-Rahme for its Autumn-Winter rave-luxe collection

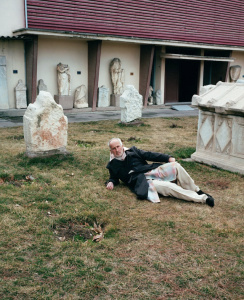

The words “I dreamt I was dreaming,” flash on screen, the text mirrored in Arabic script. Later, “Something in the angle of their shadows” flashes by, bathing limbs in light. Once again, London-based QASIMI has thoughtfully combined its home, Middle Eastern heritage and genuine ties to art through their recently dropped Autumn-Winter collection. Part runway, part installation, the work of Palestinian multi-media artists Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme has been incorporated into the online launch and is even embedded in the clothes themselves. Their film, Incidental Insurgents Part 3 (2012-2015), is given new and unusual life projected within the cavernous Printworks space that is normally home to writhing bodies and 130 BPM. Club culture is not merely pointed to in a shallow window dressing manner, but central to the collection. Fluidly mixing British 90’s rave and their generous silhouettes with luxurious matte and satin details, pieces also slyly reference traditional garments from the Middle East and North Africa, the iconic Keffiyeh scarf diffused throughout via patterns and fabric, alongside Berber-inspired parkas. Other partnerships include For Freedoms – an artist-led organisation that encourages creative civic engagement and direct action – on a selection of casualwear pieces, as well as the calligraphic work of artist Walid Bouchouchi.

To celebrate the launch, Port caught up with creative director Hoor Al-Qasimi, together with Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme, to discuss the rich collaboration and how art may create new and liberated imaginations.

When did you first come across Basel and Ruanne’s work?

Hoor: Myself and Basel had worked together before the Sharjah Biennale, where the work was originally commissioned for in 2015, but when Khalid (the late founder of QASIMI) first saw Incidental Insurgents, he truly admired it. It stayed as part of his mood board and inspiration for quite a long time, and I’ve been following their work ever since. It’s important for us to continue working closely with artists that have similar passions, values and ethics. Whatever cultural field you are in, if you share the same things that you want to fight for, collaboration is crucial, and it’s vital that we talk about Palestine and civil rights. Through my work as a curator I know the importance of trusting and working with artists, however coming into the fashion world, I’ve noticed artworks used as hollow gestures, gimmicks. For me, it’s key that creative partners and collaborators like Basel and Ruanne get the credit for the work that they put in, so that it’s a real partnership.

What is Incidental Insurgents about?

Basel & Ruanne: It’s a long project composed of three different parts, looking at figures that seem incidental to revolutionary moments, or movements, or stories that are not included in revolutionary narratives. The third part – what has been used together with QASIMI – came at a time after what many felt was the failure of the Arab revolutions. For us it was an attempt to think about how can we not see it as a failure, but as a kind of incomplete project. How the impulse towards freedom and justice keeps returning in different forms. So even if a particular moment seems like it’s crushed, it’ll return 10, 20, 30 years later. It is about experiencing those kind of heartbreaks, but also feeling the power of this impulse that doesn’t die. We’re sampling texts from a lot of different writers, including Victor Serge and Roberto Bolano, and were thinking about the ways in which sound and rhythm doesn’t die but accumulates, how it can be buried only to return at a different point. The third part is about becoming shadow, but at the same time, how you re-form.

That puts into the context its beautiful title ‘When the fall of the dictionary leaves all words lying in the street’? There’s the fall, but then also the opportunity that those broken tools or words remain, dormant, ready to picked up and used again. How do you think the work, its meaning and context, shifts when its incorporated and projected in a space like Printworks, alongside QASIMI?

Basel & Ruanne: We’re interested in disciplinary working, in the sense that we’re working with political ideas that are also very personal for us. Always wanting to find a way that these ideas can move and travel into unexpected places, or places maybe they shouldn’t be in. We enjoy collaborating with the music world, publishing, academia and activism. It’s crucial for us to understand how can the work infiltrate other spaces and even mutate as it travels, and in a way, gain a different resonance. That’s significant because we always have an anxiety about being trapped in the art world, where it’s only accessible to or engaging certain audiences. We encourage these different forms without compromising what we’re trying to say. We already had a close relationship with Hoor and we really feel that we are involved in a joint project of solidarity and struggle that we are all encountering in the current world that we live in, whether it’s Palestine or beyond. If someone was just interested in the work as an aesthetic dimension of a fashion show, then it wouldn’t have worked for us.

The medium can change and be disseminated in different forms, as long as the message is shared. Hoor, what are some of the things you wanted to bring to the fore with this collection?

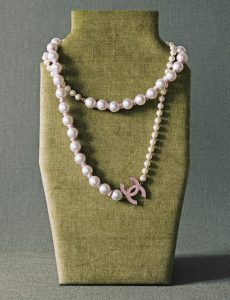

Hoor: We celebrated the Keffiyeh scarf, which is subtly diffused through pattern in a referential nod. I was also looking at nineties British rave, so we have the colours of lime green, acid yellow and gummy grape, alongside some rich pan-Arab colours of red, white, black and green. The idea of ‘tux deluxe’ also came in and informed the idea of going out, dressing up, and feeling elevated. So, some of the quality and details are quite luxurious, but at the same time it’s lively and bright.

Basel and Ruanne, I was struck by something on site saying that your work examines landscapes locked in an ‘endless present’. When Palestinian dreams, their futures, as well as their historical claim to land, to their heritage, their past, when both those things are challenged and undermined on a daily basis…in this endless present, what quality does life and art take on?

Basel & Ruanne: This is something we constantly speak about together, the way in which our imaginary itself becomes captured and colonized in the sense that you become unable to imagine a different set of possibilities. That’s where I think all the arts are incredibly significant, in the way that they can open up that space for a different imaginary. They can reveal the breaks or gaps that could allow us to project a different way of being, or a different possible future. We think about our work as operating in a sort of virtual time. It’s not an immediate future, but a virtual time of what could be. Keeping that space alive is critical. When you are locked in this perpetual present, you must keep that imaginary space alive because that’s what gives you the strength to resist. Create the things you want to see.

What new political language and imagination is needed so that Palestine doesn’t just exist without threat of persecution, but thrive and grow?

Basel & Ruanne: Pertinent to this question is how artists can work with one another, or how can people can work with one another to create different ways of relating to community formations or lines of solidarity. These sometimes small parts come to fruition and create something much larger. We can already see a shift in attitudes on Palestine, I feel that there is increasing awareness of what is actually happening, and that’s not just the work of activists, but writers and artists and musicians. We need to keep working that way across communities and disciplines to think about how different struggles intersect. How we live in one world where we’re often facing similar systems of oppression, the same types of erasure.

There’s also a great practicality to the partnership in that the special t-shirt and hoodie in the collection will have its proceeds going to Defence for Children International – why did you choose this organisation?

Hoor: It’s an important one for me because I grew up in the UAE watching a lot of news and what always shocked me as a child was seeing images of Palestine. I have some images I don’t forget. These children need their rights supported and help with trauma. Sometimes it’s important to be specific about certain causes and charities – people need to understand that childhoods are being taken away.

There is a shocking statistic about the high levels of PTSD for Palestinian children. This also loops back to our discussion about fostering alternate futures, where is a better place to start than the younger generation?