The V&A and Gucci celebrate the art of menswear

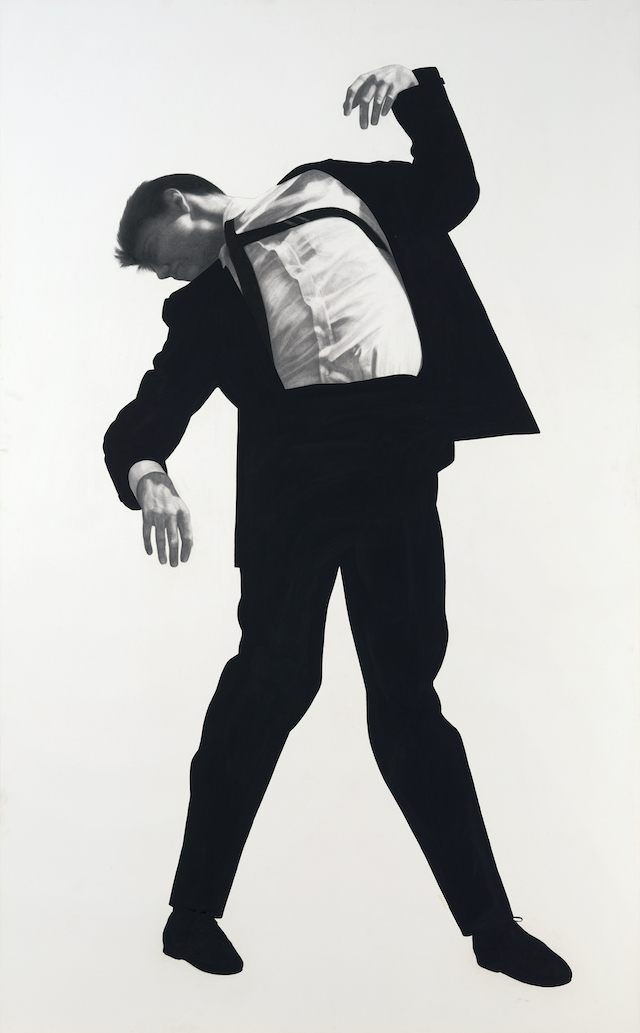

In 1988, Matthew Bourne brought campaign stills to life. It was then that the English choreographer debuted Spitfire. A success that predates dances such as his all-male take on Swan Lake, and now part of Bourne’s repertoire, Spitfire was billed as an “advertisement divertissement”.

Divertissement because the choreography is founded in the tradition of the Pas De Quatre dance, which ballet impresario Jules Perrot introduced in 1845 as a sort of high-octane interlude to bigger pieces, with four dancers mastering a series of classical ballet steps, focussing on execution above narrative. Advertisement because for Spitfire, Bourne had looked to men’s underwear campaigns to inspire his choreography. And so, dressed in all white cotton – singlets, Y-fronts and long johns among their get-ups – Bourne’s quartet got into poses more regularly seen in 2D, on the pages of mail order catalogues, or perhaps billboards, rather than on the stage.

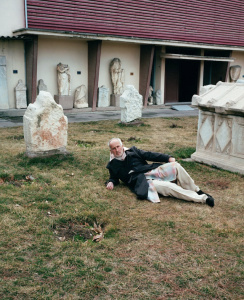

A later version of Spitfire now counts among the roughly 100 artworks on display at London’s Victoria & Albert museum, shown alongside a further 100 outfits conceived by both household names and emerging creatives as part of the museum’s blockbuster exhibition ‘Fashioning Masculinities: The Art of Menswear’. Because after all, masculinity is part performance, too.

“It’s really coming out of that moment of Calvin Klein adverts, where everything is sort of super sexualised, super physical, super muscular,” the exhibition’s co-curator Rosalind McKever explains of Spitfire. “It’s a gorgeous piece because it’s funny. It’s not teasing anyone in particular, but it is teasing this idea of rigid masculinity. Which is kind of a beautiful metaphor for what we are trying to do with this show altogether. We are taking menswear seriously but doing so in quite a playful way.”

With exhibition design by JA Projects, commandeering three galleries of the museum, the V&A show was realised in partnership with Florentine fashion house Gucci. Instead of a chronological, linear walk-through, co-curators McKever and Claire Wilcox worked to three themes. Theirs is a collage-like capture of how masculinity has been defined from the Renaissance to the present day.

Bourne’s work can be found in the ‘Undressed segment’. Here, changing concepts of masculinity are traced in the male physique, in what is often quite literally covered by fashion throughout history. “Our first gallery is really about the body, and begins with the body as something as fashionable as the clothes that are put onto it,” says McKever. Here, the body is explored as “a basis for fashionability”. Nude or partly clothed, the body is seen in photographs by Robert Mapplethorpe, Lionel Wendt and Bruce Weber, the latter shooting campaign imagery for Calvin Klein. And in classic sculptures of deities too, such as the Apollo Belvedere in marble, or the Farnese Hermes. Real life physiques are laid bare in a see-through ensemble by Parisian fashion designer Ludovic de Saint Sernin, or helped along to perfection by designers such as Jean Paul Gaultier manipulating fabric to great effect.

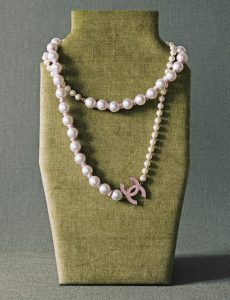

Quite the opposite, perhaps, is the exhibition’s second theme; ‘Overdressed’ homes in on the masculine wardrobe of social elites. Here, the body is clothed in prestige fabrics (silks, velvets and embroidered cloths among the offering) to manifest influence, and also affluence. Drawn from the museum’s collection and loaned nationally, portraits show aristocrats of centuries past; these are placed near finery designed and made by the likes of Grace Wales Bonner.

In a section debating the colour pink, a look by London-based talent Harris Reed – in metallic pink, the two-piece is fitted with ruff-like lace collar – is displayed near a likeness of Charles Coote, 1st Earl of Bellamont, dated to the 1770s and finished by society painter Joshua Reynolds. It’s one McKever’s favourite juxtapositions within the show, “… as this icon of patriarchy is wearing chivalric robes; but the pigment in the paint has faded from a bright scarlet down to a baby pink. He’s there, draped in pink with feathers on his head and he just becomes so camp. So, these ideas of what masculinity looks like have been shifting constantly over the centuries.”

The exhibition comes to a close with ‘Redressed’, a theme exploring the birth and legacy of the tailored suit. And although here elegance is refusal, creative flourish also enters the masculine wardrobe through, for example, the modern interpretation of traditional frock coats, as masterminded by Miuccia Prada, Alexander McQueen and Raf Simons.

But why look at historic and contemporary definitions of masculinity now? To Alessandro Michele, the show coincides with a gradual freeing from rules and codes. “It seems necessary to suggest a desertion, away from patriarchal plans and uniforms. Deconstructing the idea of masculinity as it has been historically established. Opening a cage,” Gucci’s artistic director writes in a foreword to the exhibition’s catalogue. “It is time to celebrate a man who is free to practice self-determination, without social constraints, without authoritarian sanctions, without suffocating stereotypes.” Clothes or no clothes.

This article is taken from Port issue 30. To continue reading, buy the issue or subscribe here