For Mies van der Rohe, the house was an exercise in restraint. His unrealised 1931 Row House, built full-scale for the first time in the Tokyo National Art Center’s Living-Modernity exhibition, embodies that ethos. The exhibition explores how architects – from Mies to Lina Bo Bardi and Le Corbusier – designed new ways of living

Mies van der Rohe was an uncompromising teacher. Over and over again he set his students at the Bauhaus the same problem: to design a single-storey one-bedroom house facing a walled garden. His teaching style was described as laconic. Supposedly he would sit silently smoking a Havana cigar for minutes on end, and then ask his students to try and design the house again. Occasionally he would reach for a pencil, lean over a drawing and suggest a better place to put a door, realign a wall or reconfigure the layout of a kitchen. Howard Dearstyne, one of the handful of Americans who studied at the Bauhaus, defended Mies’ approach. “The very simplicity of these houses is their chief difficulty. It is much easier to do a complicated affair than something clear and simple,” Dearstyne argued. It’s a point well made. The individual house is closer to a poem, in which every word has to count. There is much more room to be vague about design decisions in museums, the preferred building type for most architects.

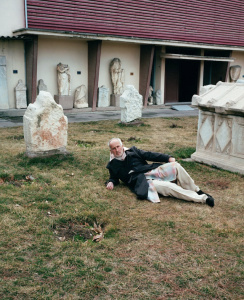

A full-size realisation of one of Mies’ own designs for a courtyard house, the so-called Row House (dated to 1931) is the centrepiece of Living Modernity: Experiments in the exceptional and the everyday, an exhibition curated by Waro Kishi and Ken Tadashi Oshima and taking place this summer at the National Art Center in Tokyo. The exhibition takes the single-family house as its starting point, and uses it to trace the way that architects have experimented with new ways of living. Kishi describes the exhibition as a historical response to the Museum of Modern Art’s International Style exhibition held in 1932. “Our idea was to show that modernism developed in different ways around the world”.

To judge by the 14 homes designed between 1923 and 1978 on which the curators chose to concentrate, spanning the long half-century that coincided with the high point of modernism, architects did a lot of experimenting on themselves. This was a period that came to be associated, at least in Europe, with social housing: blocks of communal apartment buildings set in parkland, built by municipal authorities. The exhibition does hint at that, with its coverage of the mass-produced low-cost Frankfurt Kitchen, the mother of all fitted kitchens, designed by the pioneering Austrian architect Grete Schütte-Lihotzky. But most of the emphasis is on the individual home.

Eight of the 14 homes are houses designed by architects for their own use, and a ninth – a villa on Lake Geneva – was built by Le Corbusier for his parents. The exhibition benefits from its context. Four of the houses are in Japan, and reflect a subtler selection than a Western curator would likely have chosen. There is nothing by Kenzō Tange or Arata Isozaki. Instead there is Koji Fujii’s Chochikukyo house in Kyoto from 1928, a delicate fusion of Japanese tradition with traces of western modernity. Nobuko Tsuchiura was one of the first women to train as an architect in Japan. She and her husband Kameki, also an architect, both worked for Frank Lloyd Wright while he was building the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, and then spent two years with him in America before setting up their own studio. Their villa in Tokyo, a four-storey-high timber structure from 1935, shows the spatial lessons that they learned from Wright.

Japan’s post-war reconstruction is represented by Kenji Hirose’s steel framed SH1 house from 1953, the first in a series of 60 private houses that he built in the course of his career. Completing the exhibition’s insightful account of the development of modern architecture in Japan is the Sky House that Kiyonori and Norie Kikutake, founders of the Metabolist movement, built for themselves in Tokyo in 1958.

The non-Japanese houses are more predictable, though it is interesting to see Le Corbusier represented by the very modest villa that he built for his parents on Lake Geneva, rather than one of his more palatial houses. Pierre Chareau and Bernard Bijvoet’s Maison de Verre in Paris, the ancestor of Richard Rogers’ variety of High Tech architecture, is on most lists of houses that changed the course of 20th-century architecture. It is also one of two houses in the exhibition that were designed for doctors. The other is Louis Kahn’s Fisher House from 1967 in Hatboro, Pennsylvania.

Eero Saarinen’s house for Irwin Miller reflects the interest that this exhibition has in the furniture and fittings that architects designed for their houses. Mies designed the Brno chair for the Villa Tugendhat. Saarinen asked his friends Ray and Charles Eames to design the aluminium group seating for the house that he built for Miller in Columbus, Indiana. The most recent design in the exhibition is Frank Gehry’s radical makeover of a suburban bungalow in Santa Monica from 1978. The most beautiful is Lina Bo Bardi’s Casa de Vidro. She left her native Italy to live and work in Brazil where she managed to put modernism to work for social purposes.

But perhaps the most intriguing exhibit, the one that makes a trip to Japan essential for architecture enthusiasts, is the chance to experience full-size realisation of a house designed by Mies in 1931 but never built. “There are many unbuilt houses that we could have constructed,” says Kishi. “But we chose the courtyard house because it is still a very efficient building type, and is a real option for a contemporary megalopolis like Tokyo.” Unlike the opulent villa that he designed for the Tugendhat family in Brno at almost the same time, which is also on show, Mies’ so-called Row House reduced domestic life to its essentials. Brno has quarters for servants, a greenhouse, and a motorised window wall that can open the living room up to the garden in summer. The Row House has a very reduced square plan, and was designed to be built in continuous terraces along a street. It has a single sleeping space, a dining area, a living area and a galley kitchen, all planned around an internal courtyard that creates a serene inner world.

Constructing the house demanded a certain amount of creative imagination from Kishi and Naoyuki Nagata, the architect that he worked with. “There were only a few sketches in MoMA’s archive in New York, and they didn’t give us much to go on in choosing materials, or in the scale. So, we opted for a completely white abstract mock-up. We worked as if we were members of staff in Mies’ office, trying to understand his design and imagining his hidden intention. It was a great experience for any architect. We were bridging a gap in time of 90 years to work with the master.”

The courtyard is a theme that Mies kept returning to in the 1930s, in between the construction of his three domestically scaled masterpieces; the Tugendhat villa from 1929, the Barcelona pavilion opened in the same year, and the Farnsworth House designed and built between 1945 and 1951 in Illinois. He set the theme as a student exercise; he explored it in unbuilt projects for his own clients, and in the Berlin building exhibition of 1931, The Dwelling of Our Time, when he commissioned Marcel Breuer, Walter Gropius, Lilly Reich and others to design and build show houses that reflected their view of what the contemporary house should be like. The houses were built full-size in a huge exhibition hall, and represented a remarkable act of faith in the future, given that it opened just two years before Hitler’s seizure of power, and the desperate economic conditions of the time. It was a period when Mies believed that radical architecture had a lot to offer society. As he wrote in his justification for his selection, “The dwelling of our time does not yet exist, but changed living conditions demand its realisation. The precondition for this realisation is the clear definition of actual dwelling needs; this will be the main purpose of the exhibition, a further task will be to demonstrate the means required for the satisfaction of the dwelling needs, only that way can we combat the present discrepancy between real dwelling needs and wrongly directed expectations, between genuine demand, and inadequate supply. To overcome that is a burning economic necessity and a precondition for cultural reconstruction.”

Mies’ own contribution was another single-storey house built around a courtyard, albeit on a larger scale than the row house in the Tokyo exhibition.

Phillip Johnson, the curator of the International Style exhibition at MoMA, and himself an architect, wrote of Mies’ Berlin house, “The walls are mainly glass with one solid wall facing the street. In spite of the use of glass and the fact that there are no interior doors except the ones that lead to the kitchen, privacy is not lacking. Ornament is absent in the Mies house, nor is any needed. The richness of the beautiful woods, the sheets of plate glass and the gleaming chrome steel posts suffice. The beauty of the house lies in the handling of the walls as planes and not as supporting elements, Mies places these planes so that space seems to open up in every direction giving the feeling of openness that perhaps more than anything else is the prime characteristic of modern architecture.” He could have been describing the Row House that we can see brought to life in Tokyo.