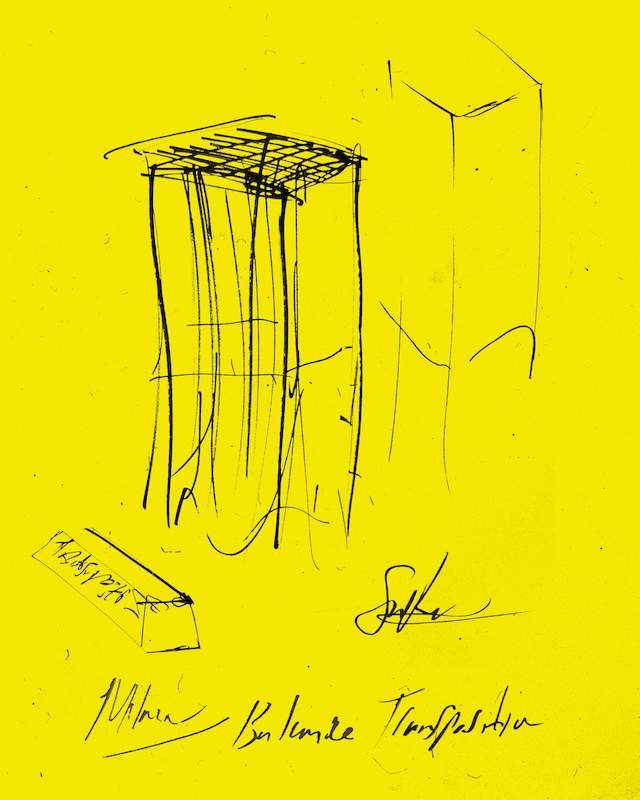

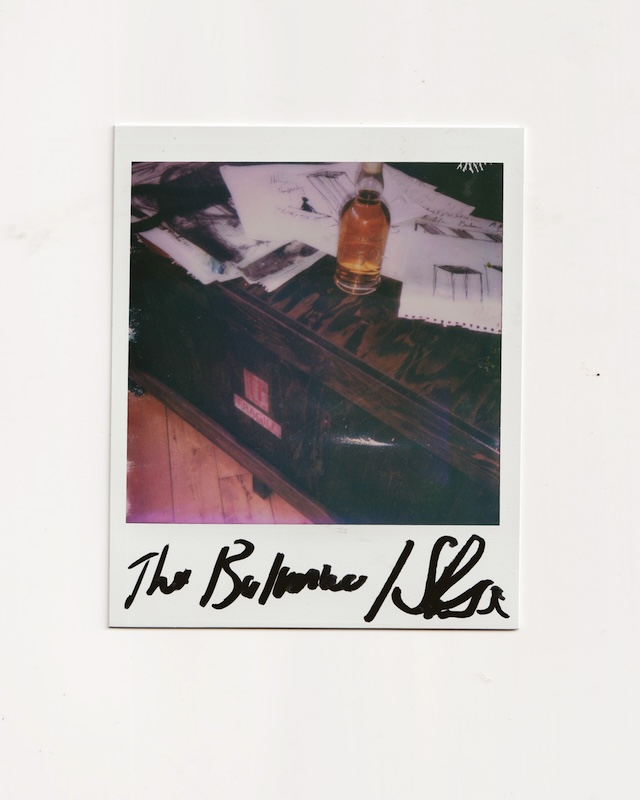

Samuel Ross speaks on TRANSPOSITION, his immersive installation for The Balvenie at Milan Design Week, and how craft, emotion and experience shape the next chapter of his career

Last year, Samuel Ross entered a new chapter. Having sold his stake in A-COLD-WALL*, the designer and artist began what he describes as a renewed decade – an ongoing recalibration of identity and output. “It’s an interesting time where everything we’ve built as a sense of identity is tied to this idea of youth,” he tells me. “As soon as you leave that – which is at age 30, I believe – it’s: who actually are we? And we almost have to rediscover, re-articulate ourselves.”

It’s a perspective that’s stayed with me since we last spoke for a profile in Port’s sister magazine, Anima, and one that resonates more deeply now as I also enter my early thirties. For Ross, renewal is more than a shift in mindset. His trajectory has moved steadily from graphic T-shirts to institutional exhibitions, from the language of streetwear to that of sculpture, painting and now, immersive spatial design. And yet the foundations remain the same: self-sufficiency, tenacity and an obsession with material. “The idea of work-life balance feels absurd to me,” he says. “The work is inseparable from who I am.”

His latest commission, TRANSPOSITION, encapsulates that ethos. Developed in collaboration with The Balvenie and unveiled at Milan Design Week 2025, the large-scale installation transforms the atmospheric Old Foundry in Milan’s Isola district into an abstract sensory environment. The site-specific work marks the first partnership between The Balvenie and Ross’s studio, SR_A, and draws on elements from whisky making – copper, oak and flowing water – as well as The Balvenie’s dedication to craft. Upon entering, visitors are greeted by a gust of wind infused with floral and earthy notes. Cascading water sounds fill the space, forming a natural rhythm alongside soft, percussion-less music. It’s a tactile experience, housed within exposed concrete and steel, where every sensory element, from mist to material, has been carefully orchestrated.

The installation also aligns with the release of The Balvenie Fifty Collection, a rare three-part series of aged single malts that celebrate five decades of craft. Like the whisky it honours, TRANSPOSITION is measured, deliberate and layered. “How do we offer people something they can’t experience online?” Ross asks. “It’s really leaning into this idea of performance, installation and runway, to deliver something worth visiting.”

In this Q&A, Ross reflects on the making of TRANSPOSITION, how the definition of the craftsperson is evolving, and what this new phase in his practice looks like – one that’s matured, sharpened and entirely self-defined.

So tell me, what stage are you at now?

There’s a space of economic freedom, which I’m super grateful for, because I spent the last 12 years working 14-hour days, every single day. That’s not changed. Work is all I do, and I couldn’t see another way of living where I don’t. I’ve always built companies or value and placed them into a market or a context or an institution. There’s never been this guise of provision coming from outside of myself. I have to establish the value in the market, which is a great affordance – to not have to run away from the work – because the work is inherently part of my identity. And the output, as we were saying, evolves and matures over time. Perhaps, arguably, you can say it’s moved from spray painting a T-shirt to abstraction in the metal at the V&A. There’s been a development. But the way of producing work hasn’t necessarily changed.

Do you think you have a healthy work-life balance?

No, probably not. I sleep well. If I feel like I have a mental block or creative block, I’ll go to the gym or I’ll paint as an unlock mechanism. But fundamentally, I’m aware my entire life is dedicated to producing emotional works that will go out into the world. And I couldn’t think of a better, more fulfilling practice.

Are you still doing your painting?

Indeed. I have a solo show at the moment at SCAD Museum of Art, which went live last month. It’s my first American survey of an institution. It will sit there for about six months, and they’ve just acquired three pieces of work, which is fantastic.

It’s the first time that there’s been a survey of the work between garment, sculpture and painting in a single space, which is very exciting, because it gives an opportunity to see the cohesion between the work. And I was saying earlier to another member of our crew: it just takes a series of years to establish continuity across the disciplines. And finally, that’s now quite palpable.

Would you say that’s the definition of success?

I think that’s for other people to determine. But I feel there is a sense of synergy and cohesion between the messaging, the storytelling, and the application of the work – whether it be the aesthetics, the materiality, the scale, context, the potency. I know where I sit within the dichotomy of the arts, and it’s a place I want to continue to establish further.

You’ve talked a lot about craft as something inspired by your family and your parents. Do you think the definition or purpose of a craftsperson has changed over time?

I feel over the past decade we went through a spur of growth when it came to expression and creativity, whether it be luxury consumer goods or new artists entering the canon. There’s always a delicate dance between leveraging a moment of growth and ensuring we’re still making the right decisions with the work. Arguably, now the market is just adjusting and restabilising, which gives artists more time to really think about the work being put out there.

And bring more traditional techniques and methods of making to the fore?

Yeah, I agree. Now, the artist’s practice ideally has more time to think about what value they bring to the market. It might be the extension of a particular movement. Like for myself, it was looking at Black British abstraction, seeing there are so many missing holes or cavities within the canon, but still being quite discerning about what I have to offer to that canon. For me, it was about material – like including volcanic ash from the Caribbean islands my family hails from, with turmeric and ink and pigment and honey – to offer a new material composition within the lens of abstraction. That was the research that occurred over the past few years. And from a craft standpoint, it’s also about the quality of craftsmanship in the maker. With some of the partnerships we’ve structured through SRA, we only work directly with families who are still involved in the running of their organisations and companies. It’s typically a value proposition tied to learning how ateliers and maisons function. Because fundamentally, I want to build a maison from SRA across the next 10 to 15 years, which will sit parallel to my practice. But as a company, it will take on the behaviours of a maison.

How would you define that?

There are modern versions of maisons now which are really interesting: the Byredo that Ben Gorham has established, or 1830 L’Officine Universelle Buly that Ramdane Touhami has recontextualised and grown. Those are the two I look at, because they have a new tilt on what European luxury looks like for a particular generation. Perhaps they’re closer to Gen X, but as a millennial, I’m searching to determine what that can be for our generation. The beauty of the maison model is that it takes time to establish it, which means you have less pressure to bring your ideas to market.

In terms of the installation for The Balvenie, you mentioned you like to bring in new materials or unexpected mergings. Do you think you’ve achieved that with the installation?

When it comes to spatial installations, you have a few different KPIs to establish. One is that the main actor in a commercial partnership needs to be the product itself. Hence why there’s such a focus on the animation of water and this idea of different stages of the fermentation and distillation process leading to whisky from a raw mineral well. Particular aspects are quite clear to understand. When it came to material – after visiting Dufftown – the focus on patinated copper and lacquered oak were two extractions brought into the install here. But also, as an artist, you’ve got to be gracious to the resources each partner has to put forward. There’s a dance, always pushing to articulate things well. Each partner has a different capacity for what can be delivered. If we think about Kohler last year, for example, you could imagine the capacity put forward there was in the millions to establish such a grandiose approach. When you’re dealing with private European companies, it’s a much more delicate and intimate process and output. In this instance, it was more about delicacy and intimacy – not necessarily pushing The Balvenie into a distortion through a heavily abstracted environment with lots of plastics and a postmodern building. That wouldn’t make sense for The Balvenie. If I think about The Balvenie, I think about procurement, almost – finding ways to bring installation in, but also preserving and making sure there’s a sense of comfort. It’s the first time the brand has ever been introduced in that way.

It’s very intimate. And I think what elevates that is the sensory experience.

When I think about performance art and installation, it’s more about what can be conveyed in person that can’t be conveyed digitally. How do we drive people to the space? And if they are coming to the space, how do we offer them something that can’t be online? It’s light, temperatures, the animation of water, the flex of the water, the mist according to the body, the temperature shift and the scent. It’s really leaning into this idea of performance, installation and runway, to deliver something worth visiting.

Do you think that installations therefore need to have that performative element? I’m aware you often apply that to your work.

I think back to runway shows at A-COLD-WALL*, where we had misters dispersing water onto models and the audience, or models running through black water. This idea of installation and performance and environment comes down to a love of public art. How do you enamour the public with emotion first? It’s interesting – when you sit between this weird gorge or blur between design and art, there has to be enough intent with design. It’s always the assertion of justifying, justifying, justifying – because there’s typically a clear conversion point. Whereas within the arts, it is much more of a Jungian or psychedelic experience of being arrested by an emotion or a reality on behalf of the artist. And with spatial installations, you’re mediating the two, finding a way to bring them together.

A psychedelic experience – I love that. So is that how you expect or hope visitors will experience it? To walk in and have a psychedelic moment of respite?

I think it’s more that they enter the space and the temperature drops, and the acoustics delivered from the water – that sense of percussion and animation, which dances quite well with the soundtracks playing within the space – offers them respite in the midst of the city. There’s enough abstraction of what you expect from a corporate partnership offered from that experience, but it still supports how special and potent the whisky is itself, through the volume of water being presented.

Do you think you’ll continue working in this space, that being collaborations with alcohol brands?

I think it’s pretty interesting. Before we go into any category, I do a lot of R&D – who else has activated the space historically? And I think with the maturity of my career moving forward, these are the keystone moments that define an artist’s impact on a generation. You’ll do an alcohol partnership with some kind of synchronicity, whether it’s Gary and Hennessy, or Murakami and Hennessy, or Futura and Hennessy, or Virgil and Moët, or Kim Jones and Moët. It’s a space artists consistently inhabit. Historically, artists and alcohol partnerships lead to artistic commissions. It’s actually just a part of the creative economy. We’ll stay within that remit. This will expand and tour – potentially globally – which is great. North America and APAC are currently on the cards.

Congrats!

It’s just been an incredible, incredible process. It’s the first moment of many to come, and you’ll see this really start to scale up and take new forms.