Kusheda Mensah’s designs have always encouraged connection. Now, as a mother of two, her practice is shifting

There’s a semi-circular pouffe that plays a central role in Kusheda Mensah’s home. It’s a simple shape, thigh‑height and thickly cushioned, upholstered in a fine off‑white and brown checkerboard Kvadrat twill. It stands, it rolls, it’s readily repurposed and moves around the room. For her young children Sior and Soleil, who are four and two years old respectively, it’s a seesaw or a step‑stool – another excuse to be always in motion. For Kusheda, the pouffe doubles as an unlikely (but very gorgeous) desk chair; though she has had many studio spaces, she works mostly from home, happy and at ease in the window of her south‑east London living room.

Though it’s far from the best‑known piece her brand, Modular by Mensah, has made, this pouffe is a pleasingly powerful expression of Kusheda’s practice as a designer. Bold, functional and playful. “Things can be so simple,” Kusheda tells me from her spot on it, on a Tuesday morning early in spring. “I’m always thinking about how I want people to feel.”

Modular by Mensah first launched in 2018, as part of a showcase to the great and good of the design industry at Milan’s Salone Satellite, a fair dedicated to the most promising designers under 35. From the moment the doors opened, she drew a crowd. Her first collection, Mutual, harnessed rich, warm colours, tactile textures and expressive shapes to encourage interaction – and in so doing, enhance social wellbeing. “A seat is a seat, a pouffe is a pouffe – people sit down, they get up, they go,” she says. “Modular by Mensah is about creating shape that changes the flow in a room. In public spaces – a foyer, say, or a gallery – it’s hard to feel like ‘I’m here now, let me just relax.’ I want people to feel able to be still, to engage with their environment, but also to engage with one another.” This aspect – creating a focal point that encourages conversation, interaction, exchange – is crucial for her. “Without community, who are we?” she asks. “A big part of why Modular by Mensah exists is to bring people together. That is so important to me, personally, and my practice was born out of wanting to do that for other people too.”

Now, seven years since it was founded, the spirit at the core of Modular by Mensah is stronger than ever – but Kusheda’s practice as a designer is growing, evolving and deepening around it. She has grown, birthed and nurtured two small children in that time – a seismic shift that feels all the more tangible because we are friends and neighbours, and I’ve been doing something similar, sometimes together with her, in my own home two doors down. (She is the kind of comrade that an expectant parent dreams of sharing the toddler years with: warm, thoughtful, fun, real – generous with her time and energy, always, even when both are in short supply.) In early motherhood, life becomes an elaborate rear‑ranging; the pieces are painstakingly carved out, set next to one another, then thrown up into the air to scatter and reorganise again. Where once the ‘modular’ in her name spoke to the way objects coexist in a space, now it speaks to something greater, more abstract, and rich with possibility. Different materials. Different fabrication techniques. Different people. There are so many different parts that make up the whole.

Kusheda came to furniture design by way of textile design, which has always been her first love. Born to Ghanaian parents and raised in London, texture and print are embedded in her cultural identity. “When I was growing up, my mum was always picking out fabrics for a particular occasion, looking at colours, textures, symbols,” she says. She studied Surface Design at London College of Communication, where she was drawn first to printmaking, before she began exploring the ways structures could disrupt or redirect how a space is used. Lately, she’s been experimenting with printing again. “How can one symbol be broken down and multiplied through printmaking to create an immersive experience?” she asks, thinking aloud and talking loosely through some recent tests. Printing offers her a welcome return to process, absorption and experimentation.

Symbolism plays out in her work in larger ways too. Last year she began exploring language, creating large‑scale sculptures inspired by Adinkra – visual symbols that represent concepts, proverbs and aphorisms in language in Ghana. “There are so many symbols that the Ghanaian community and the culture relate strongly to,” she explains. “I was exploring phrases in Twi [a variety of the Akan language] and there was one that stuck out to me: onipa ya de. It means, ‘being human is sweet’. It’s a reminder to embrace humanity and enjoy one another.”

This phrase became the title for a seating installation that she exhibited last summer as part of the 2024 edition of the Harewood Biennial, an event which celebrated craft and connection while elevating artisanal heritage. In the collection, angular and curved pieces slot into one another to create seating, exhibited within a library room. Visitors could curl up solo inside a curved form, or perch next to strangers and loved ones alike, on functional objects which represented communication and interaction on both a micro and macro level. It’s a space she’s excited to continue exploring.

A few months after the Harewood show opened, Modular by Mensah debuted another new collection at London’s V&A, as part of the London Design Festival. Against the backdrop of one of the museum’s majestic Medieval and Renaissance rooms, Unhide showed seating which combined metalwork with fine, sustainably‑sourced leather provided by Bridge of Weir Leather, to create an elevated and ambitious new collection.

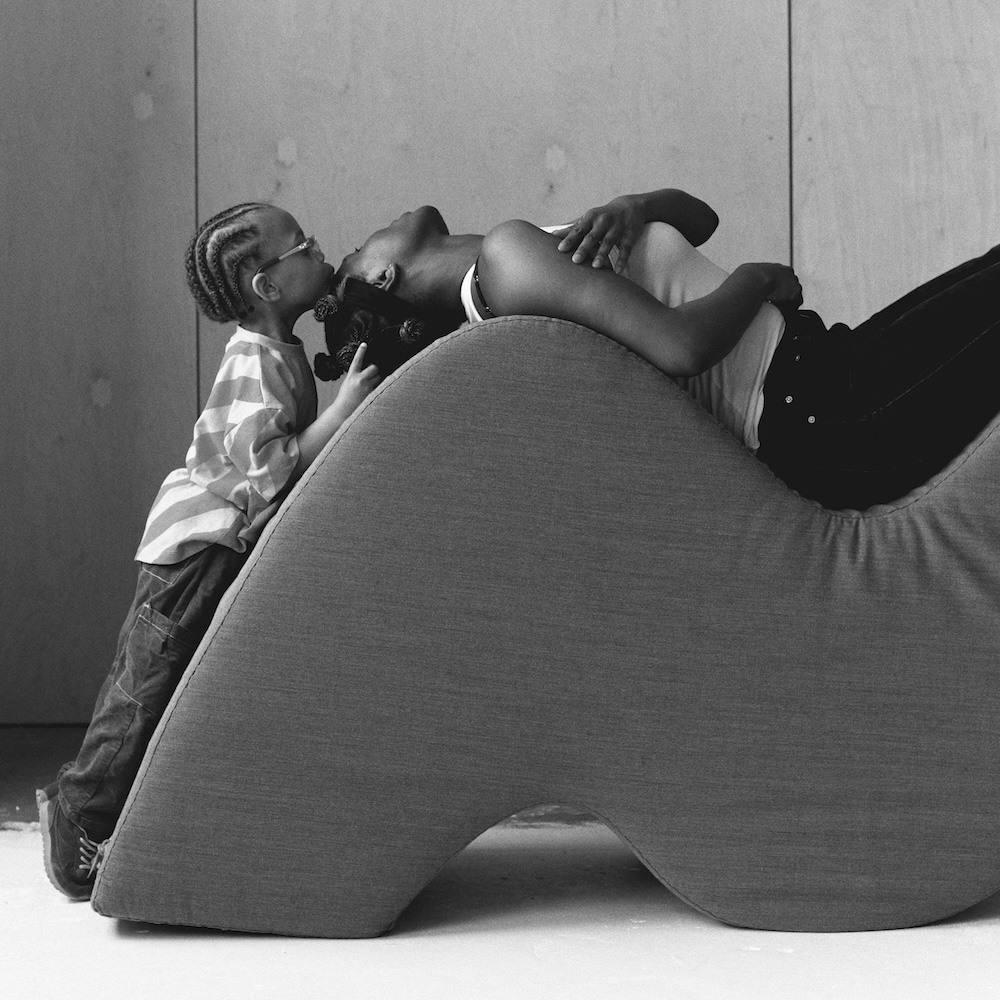

Still sculptural, still playful, but with new structure – another hint of things to come. At the Festival’s opening night, Sior and Soleil clambered gleefully over the banquette‑style elements, as if modelling to the mostly adult crowd how their mum’s work could be used.

Their joyful and intuitive interaction with these rigorously crafted pieces was a powerful reminder of the ways in which raising children can expand a creative practice. Kusheda’s vision is dynamic, innovative, vital and bold because of, and not in spite of, the ways that parenting shapes her point of view. The work is harder to get done, certainly – but it’s infinitely better for it. “I give so much to motherhood. I give so much to my career. Both are part of my identity,” she says. It’s exhausting and enriching work, but she always has one eye on the legacy she’s building. “As a Black designer, as a mum, I’m creating that representation for my children – or any precious little child, honestly, that deserves a leg‑up somewhere. My peers and I are opening the doors. It’s hard work. But one day, other people will be able to just stroll through.”

The accolades reinforce the point. In 2022, Kusheda was one of eight designers to be nominated for the coveted Hublot Design Prize. A few weeks ago the World Design Congress named her one of 25 trailblazers leading the Design for Planet movement. There’s an exciting collaboration with independent design brand Hem in the works, due to launch later this summer.

And in spite of all the spinning plates, the competing deadlines, the drop‑offs and pick‑ups and unexpected sick days, there’s a sense of space in Kusheda’s design practice right now: a fertile ground in which she’s trying out new things. Screenprinting. Textile design. Ideas for education. Books. A studio space, maybe.

These new building blocks are all becoming part of her approach – strong, flexible, always evolving, always growing. This is modularity, in practice.

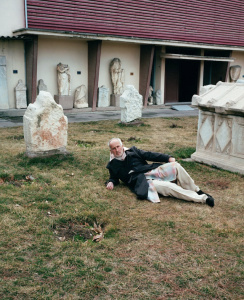

Photography Jo Metson Scott

This article is taken from Port issue 36. To continue reading, buy the issue or subscribe head here