Oxford University’s Professor of Cardiovascular Medicine on representations of our most vital and ubiquitous organ

A woman in black squints into the tilted screen of the rose-gold iPhone that she is panning across an already-agitated room. She is oblivious to what is happening behind her left shoulder. There are gasps.

A work of art is shredding itself within its frame. ‘Going, Going, Gone’, (for $1.4 million) still hangs on the wall of the Sotheby’s sale room. More precisely, it is partially shredding itself. Conserved, in the upper-right corner of the image, is a pink balloon in the form of a ‘heart’. But, remarkably, the automated theatre is more shocking than the notion of a small girl standing beneath the representation of an explanted human organ.

The heart motif has become commonplace, a shorthand for a range of diverse, yet universally recognised emotions and states of mind. If you doubt this, consult the 30-plus heart emoticons on your messaging app. Or take a walk through London or Lisbon; New York or Naples; Paris, Pondicherry or Phnom Penh. You will find street-art hearts enlivening the walls of each. Among the everyday broken hearts and arrows piercing crimson love hearts is a more mysterious icon: the heart with the black spot. What is it intended to represent or express? Where does it come from?

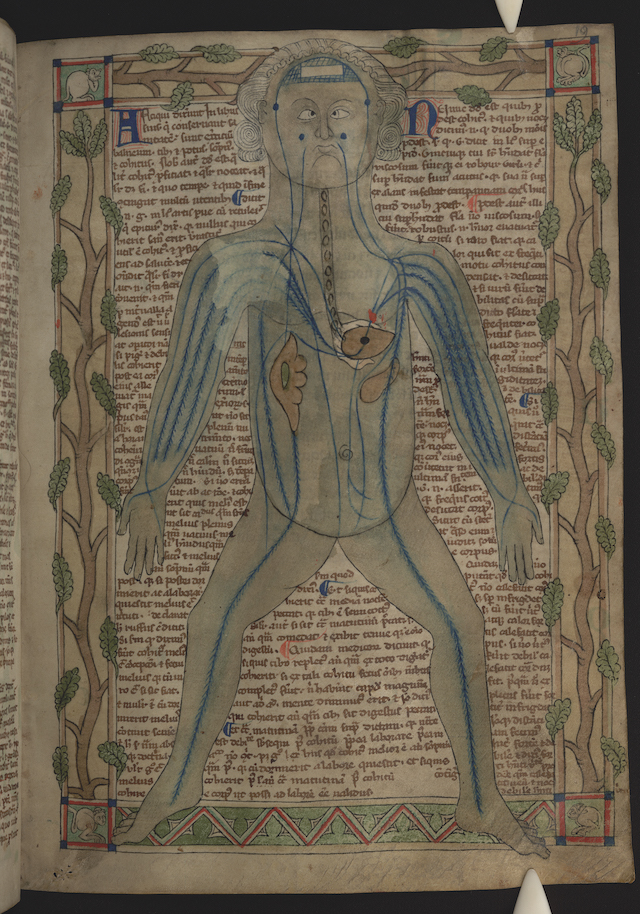

The Bodleian Library manuscript, Ashmole 399, is one of the earliest known depictions of a human heart in any anatomical context. The figure is a draftsman’s interpretation of the ‘physiological’ systems of the Roman physician, Galen. In any modern sense it is full of errors, since the anatomical plumbing of the heart and vessels was barely understood. There was no knowledge of the circulation of blood; in Galen’s synthesis, blood was made in the liver and ebbed into the tissues to be consumed. But the physiological accuracy of the image is of only passing concern. Seated within the heart is a black spot.

Scholars debate the significance of the nigrum granum (black grain). It is at once both the point of origin of the arteries and the seat of the spiritus. The accompanying text reads: “Procedunt autem a nigro grano quod est in corde in quo spiritus habitat” (Proceed from the black grain that is in the heart in which the spirit dwells). But the definition of the word spiritus, is not precise. It could refer simply to air or breath, or, more significantly, the entity that we now call the soul (anima), or the life spirit (genius anima). The Romans also described the genius anima as the source of seed in reproduction, a notion that is shared with passages from the Upanishads and early Judaeo-Christian texts.

In his notebooks, Leonardo da Vinci went so far as to portray the heart in seed-like form, from which the vessels sprouted upwards and downwards, as if the heart were in germination. In his early anatomical studies, Leonardo had inherited the conventional teaching that the heart was the source of semen and, besides drawing seed-like inclusions in the heart, he also showed an imagined vessel that plumbed the heart directly to the penis. His later works were anatomically correct, because they were not based on someone else’s synthesis or intuition but meticulous observations of his own dissections.

Clearly, none of this is a coincidence. There is no seed in the heart, no anatomical correlate – nothing that could be interpreted as a grain or node. The black seeds are an intuited human synthesis.

The human heart tells a story of human ingenuity and intuition that defies scientific understanding, and few symbols are as ubiquitous in contemporary life. I have collected hundreds of street-art images of hearts from around the world. The black spot is not so common, but it is not rare. Take for example the black cross in a heart on the wall of an alley on the Right Bank in Paris. A black cross. What does it mean? A modern mark on the soul? Or look to the vast expanse of hearts on the 2021 pandemic memorial wall on London’s South Bank. Among thousands of still hearts, broken hearts and still-beating hearts are more than a few with black inclusions in their core.

Only once have I chanced upon a work in progress. On a walk with my son along a disused railway line in North London one damp Sunday afternoon, we witnessed the creation of a street heart, almost from the beginning. I struck up a conversation with the artist. Why was she painting a heart? Why not a brain? Why had she chosen to depict an anatomical heart rather than the simpler heart motif? It was her first. She did not know.

An hour or so later we passed again, on the return stretch. The finished work filled the brick alcove. Despite the anatomical jumble, it was clearly a heart; plump with blood, its surface mapped by the tortuous coronary vessels and the flimsy cloud-like atrium mounted at the top. Striped arcs to each side denoted the pumping movement of a living heart. I was shocked to see a black spot. “You’ve painted a black spot in the heart – why did you do that? What does it mean?”

No answer.

This article is taken from Port issue 29. To continue reading, buy the issue or subscribe here