Kitty Grady encounters a multi-faceted spectrum of artwork at the 2022 Bergen Assembly

It is the official opening of the 2022 Bergen Assembly, and the curator, Yasmine d’O has been spotted on her way to the city’s central train station. A fictional character, d’O is a piece of curatorial performativity, a cheeky parody of the contemporary curator who can be as much a feature of art fairs as the art itself. Before Bergen, I had been at the Lofoten Biennale in the Norwegian Arctic Circle, presided over by Italian curators Francesco Urbano Ragazzi, (the combined name of Francesco Urbano and Francesco Ragazzi). Slightly incongruous with the remoteness of the Arctic Circle, the designer-clad duo were almost an art piece in themselves. Appropriately displayed in their ‘Data Center’ exhibition (a sort of curatorial moodboard) at the North Norwegian Art Centre (NNKS) in Svolvær was a taxidermied two-headed calf from the Middle Ages, a local curiosity of profound local pride.

In lieu of an (actual) curator, the 2022 Bergen Assembly – the title given to the city’s triennial art fair – have appointed the French conceptual artist Saâdane Afif to ‘convene’ the 2022 programme. A gentler word than curator, the etymology of convene, is to ‘bring together,’ or more appropriately still, to ‘assemble’. And that is what Afif has done. The 2022 Bergen Assembly is titled ‘Yasmine and the Seven Faces of the Heptahedron,’ after the play of the same name by Thomas Clerc. In it, the eponymous Yasmine goes on a journey to find a mysterious seven-sided shape, meeting seven characters on her way: The Professor, The Bonimenteur, The Moped Rider, The Fortune Teller, An Acrobats, The Coalman and The Tourist, each one revealing a different side to ‘the object of our dreams.’ Across the city of Bergen, seven exhibitions explore each of the characters, asking three artists or collectives to contribute in each instance: a total of 21, itself the number of edges on a heptahedron. Evading anything as symbolic or cemented as a Jungian archetype, ‘Yasmine and the Seven Faces’ instead fleshes out each character into something thoroughly three-dimensional. Afif is interested in the essentially hybrid, contradictory nature of our identity and identities, and has allowed each artist to respond freely to their assigned characters, to ‘construct, represent and dismantle’ them as creatively as they like.

‘The Professor’ is the first exhibition and fittingly takes place at the University of Bergen’s Faculty of Fine Art. The nuances of the character are highlighted in the opening work: a copy of George Grosz’s 1927 Self-Portrait as Warner. Grosz depicts himself as stocky and serious in round spectacles, wearing a shirt and tie with a blue smock jacket: the part-white collar, part-proletarian uniform of an art teacher. His gesture – an index finger to the sky – whilst initially signifying the phallic authority of Ancient Rome, carries a triangle of allusions. The gesture, as in Da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi, says ‘do not be afraid’: Grosz was working at a time when Fascism was beginning its ominous ascent in Germany (represented by the painting’s mottled background). For Grosz the teacher had the ethical choice to either perpetuate ideology, or – as the pose also suggests – to tell his students to stop; to think. Grosz was not yet a teacher when he painted the portrait and the idea of self-parody is central to the exhibition. In Myself and New York (1957), wearing lingerie and clown’s makeup, the artist, swigging bourbon, is collaged onto the city’s skyline. The self-parody expresses his feelings as a political exile in the Land of Plenty – the off-center framing suggesting his feelings of non-belonging. Lily Reynaud-Dewar also opts for parody in Gruppo Petrolio, playing an autocratic professor who is obsessed with getting her students to make a film about the director Pasolini. The project is one of performative failing: the 10 hours of mockumentary displayed are displayed in a loop of videos in an installation room designed to look like an Italian trattoria. A contemporary professor in painting at Bergen’s Faculty of Art, Lars Korff Lofthus displays his student’s self-portraits alongside his own – demonstrating how a professor not only passes on their knowledge, but must allow it to be surpassed and outnumbered.

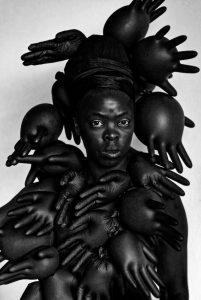

Meaning ‘the storyteller,’ in ‘The Bonimenteur’ at Bergen Kunsthall questions of fabulations and fictions come to the fore. Bernhard Martin’s shimmering paintings initially suggest fantasy, but draw on more sinister themes of money, control and deceit. Hands play an important role here too, but this time are disembodied, emphasising their literally manipulative, trickster quality as well as suppliant purpose. In Mind Candy (2021), an elegant hand in a golden bracelet ‘pricks’ a phallus with a needle, a wry comment on the gold digger. In I Thought it Was a Door (2016), a greedy hand is seduced by a €200 note, the moment between touching the currency tantalizingly suspended, the see-through string suggesting it will be pulled away any moment. GRAU’s sculpture, Bonfire, consists of giant, irregularly arranged matches tipped with glass light bulbs, a piece that explores the human act of gathering and storytelling. Mood is the message here. Benches positioned around the bonfire invite spectators to sit down and soak in the atmosphere, the lights shifting from reds and oranges to bright whites, allowing the viewer to ‘activate feelings and self-connection, to float away in dreams.’ The third component of ‘The Bonimenteur’ foregrounds the graphic design work of Berlin-based studio Neue Gestaltung, who have created posters and flags for the Assembly (with each character represented by another artistic or historical figure) which disseminate the message of the festival across the city. They have also designed Side Magazine, a seven-part publication edited by Louisa Alderton, which, with essays and interviews, takes the themes of the programme into further directions and dimensions still.

‘The Fortune Teller’ draws on the clairvoyant’s powers of foresight, but explores ideas of futurity in more cynical ways. Miriam Stoney’s Debt Verses is a poetry book inspired by the artist’s lived experience of student debt. In the book, which is beautifully designed in a continuous concertina, rather than discrete pages, Stoney conceptualises debt as a relationship to an unfolding future, as a thing that follows. The augur here is Kevin, a ‘faceless bureaucrat’ who comes to ‘solicit’ the protagonist’s future. Stoney explores ‘indebtedness’ on a metatextual level, the poem has extensive footnotes to works she has drawn from. In the shop selling the book that is part of the exhibition each work referenced is on display on a bookshelf. This works as a more positive manifestation of the future, realizing Stoney’s dream to see her own book ‘stand along other books.’ Next door, Alvaro Urbano’s work The Great Ruins of Saturn, inspired by the 1964 World’s Fair and its ‘Tent of Tomorrow’ examines the false promises of capitalist progress. Urbano has installed moving carousels of shadow puppets depicting dinosaurs, taxi cabs and Mickey Mouse heads. The work is located in an abandoned house, and with shadows cast sinisterly across the wall, this ‘projection’ of the future transforms utopia into dystopia.

The trio of artistic identities of Berlin-based JP Raether (Protektorama, Schwarmwessen and Transformella) form the three edges of ‘An Acrobats’ at Kunsthall 3,14. Raether exploits the camp, shape-shifting qualities of the acrobat in artworks that similarly critique techno-capitalist futures. In the main installation, designed to look like an Apple Store, chrome products seem to explode and glitch with ‘occult substances of witchcraft,’ whilst in a guerrilla performance trip to IKEA, Transformella, critiquing the ‘repro-industrial’ complex the furniture behemoth promotes, asks the audience – listening via headsets – to resist the shiny surfaces of BILLY bookcases and come together as a new communal family.

Fuel becomes a generative poetic substance in ‘The Coalman,’ in what is also the emotive climax of the Assembly. Located in Glyndenpris Kunstall, which sits atop one of Bergen’s many hills, Yasmine d’O herself has curated ‘A Selection of Vernacular Sculptures by Coal Miners’. These small, lovely works, made from graphite and coal, include scenes of mining life as well as devotional statues of Saint Barbara, the patron saint of coal miners. Displayed in mahogany cabinets with purple shelves, a profession normally defined in terms of extracting value, here suggests the surplus value of luxury. Claude Debussy’s composition Les soirs illuminés par l’ardeur du charbon, was written during a coal shortage through the harsh winter of 1916. Here it is music which becomes the commodity: a display with documents and letters shows how the impoverished composer sold the twinkling composition in order to afford actual warmth. Augustin Maurs’s Nothing More (2022) interrogates the idea of the voice as an immaterial medium. Inspired by the landscapes of Svalbard, Maurs’s echoing, icy composition compares musical and geological time. The airy room of the installation, consisting of ‘nothing more’ than the title of the work scrawled across the main wall in charcoal, recalls the abandoned mines, new geological structures, that now lie across the globe, largely unoccupied.

Similarly, in ‘The Moped Rider’ at Bryggens Museum, fuel is depicted not as a motor of movement, but an object of contemplation. Shirin Sahabi’s Pocket Folklore (2018) consists of vitrines displaying objects retrieved from one of Japanese sculpture Noriyuki Haraguchi’s famous ‘oil pool’ pieces. While water would have caused the items to rot – the quotidian knick knacks and detritus thrown in the pool by the public (chewing gum, pencil stubs, paper airplanes) have been perfectly preserved, and are displayed on a shiny black surface which appears infinite in depth. Quotidian objects are also the focus of Denicolai & Provoost’s project Eyeliner in ‘The Moped Rider.’ In an installation, the artist pair display curiosities they found in windows around the city of Bergen in the museum. Kitsch and eclectic curiosities that include pairs of porcelain dogs, snowflake cut-outs and model boats are proof the intrepid explorer needn’t go too far to find inspiration.

The final part in the 2022 Bergen Assembly is ‘The Tourist.’ At Permanentem, Dominique Gonzalez Foerster’s Exochambre explores the desire of the voyager to not only travel, but to enter deep zones of self-connection and new dimensions of being. An installation piece, the room is half-hotel, half-nightclub, darkly lit with a deep red carpet, a single pillar, a round quilted daybed (for waking reverie), a sequinned jacket hanging on the wall and a neon sign with the name of the work. This interior space opens onto a celestial video installation, visible through a circular, planet-shaped window: an invitation to a space odyssey. Windows play a part in Daniel Buren’s work next door. For Trahisons, the artist has created coloured vertical panels in his famous stripes, which match the position of the museum’s windows opposite. In front of each panel is a bench from which a view of Bergen’s hills can be enjoyed. In the site-specific work, the art itself is usurped by the environment – to experience it you must turn your back to it – but the stripes nonetheless provide a visual and phenomenological anchor.

Neue Gestaltung has illustrated ‘The Tourist’ with a drawing of Hans Ulrich Obrist: a wink to the famous curator’s reputation for excessive international travel. Organisers of the 2022 Bergen Assembly like to describe themselves as a ‘perennial Biennale’: as a structure which does merely pass through the city, but remains. The final side of ‘The Tourist’ is Sol Calero’s permanent installation La Cantina de la Touriste. Calero has converted the existing site of Kafé Mat & Prat into a tropical retreat – mosaic-ed and citrus-hued – a far cry from the low-lit hygge typical of Scandinavian interiors. Kate Mat & Prat is a centre providing skills training to immigrants and a dining space for nearby care home residents (offering the former ‘tourists’ a pleasant environment for integration and the latter, less mobile citizens, the novelty and visual stimulation that travel would otherwise allow). Whilst Calero has given a new life to the space, the artist explains that it has also taken on a life – or a character – of its own. ‘I came back and it was not my space anymore – there were chess classes on – and that’s kind of the purpose of the project. It will remain for as long as the canteen remains. It will adapt to people’s needs. There’s time.’