In their debut UK solo show at the Serpentine, Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst explore how AI can become an active collaborator in human creativity

We all know that AI is reshaping creativity in ways that are both exciting and uneasy. On one hand it streamlines tasks once considered solely for the human hand – writing, composing music, creating art. On the other, artists are now competing with machines capable of mimicking their styles, while filmmakers and animators are being priced out of their jobs by tools that quickly generate images and scenes without human input. Music is also feeling the influence, with AI-driven systems composing melodies, cloning artists’ voices or engaging in traditional practices like ‘call and response’ – a vocal technique that works like a conversation, which has been used for centuries to build community, preserve stories and share information across the ages, whether in work, rituals or protests. But now, we don’t even need a singer to do the singing.

Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst (of Herndon Dryhurst Studio) are long-term collaborators and partners, working at the centre – or perhaps the sweet spot – of AI and human experience. Music, art and tech tends to be their bread and butter, of which they’ve developed numerous projects that tussle with the idea of who and what should be creating art, often handing that role to the machine. Herndon, for example, is known for using AI in her music and blending her voice with the algorithm; Dryhurst is a researcher and technologist interested in how tech can reshape creative practices. Together, they’ve created Spawn, an AI vocal ensemble trained on Herndon’s voice, which debuted in 2016 on her album PROTO. Another key project, Holly+, allows users to manipulate Herndon’s voice via deepfake technology.

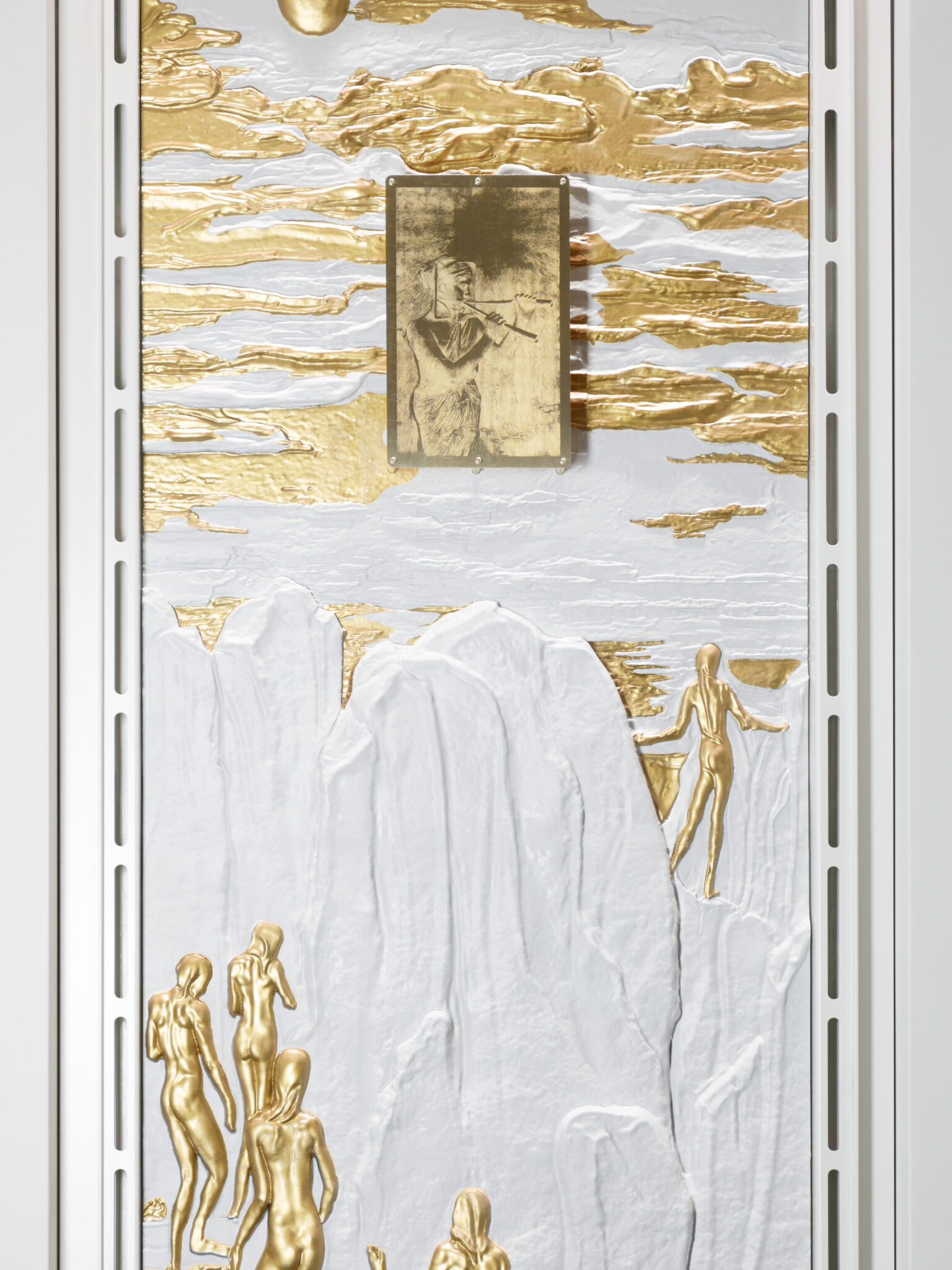

Their latest project, The Call, expands on these themes and is being presented in their debut UK solo show at Serpentine North, running until February 2025. Developed in collaboration with Serpentine Arts Technologies, the project involves AI models trained on datasets of hymns and singing exercises from 15 UK-based community choirs. Just as call and response historically built collective experiences, AI is used to augment human creativity and as a tool for collective creation. This begs the question: what happens when machines become part of these deeply human traditions?

By making AI an active participant in the creative process, The Call opens up an entirely new conversation about authorship and agency in the age of AI. Below, Port chats with Herndon and Dryhurst about the project’s development, its collaborative nature and the ongoing conversations surrounding AI’s role in creativity.

Port: What are the current societal concerns with AI and how have you addressed them in this show?

Herndon and Dryhurst: People are concerned about data provenance, model ownership, IP, creative displacement and human agency. We hope to address those issues with our practice in art and AI and this show.

Why pair with music? Can you explain how the process of training AI models with choirs became an art form in itself?

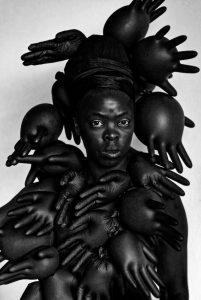

We like the choir analogy to AI as group singing is an example of early human coordination technology that produces emergent effects. We see AI models similarly, collective creative accomplishments that produce results greater than the sum of their parts. It’s important to situate AI as part of a much longer historical arc of coordination and expression. It is very human. Artificial means made by humans. AI is just us, coordinated in peculiar ways.

How did it all come together, can you give some specific details around the process/creation?

We’re thinking of the creation of the data, the training of the model, and its output all as works of art. For the show, our idea was to collectively train an AI model. This is important for a couple of reasons. People will be able to interact with the model, get an interesting insight into how a model is put together, but also the people who are contributing to the model will be able to govern and have some self-determination over their data moving forward.

We spent months training a choral AI model on voices from 15 choirs based throughout the UK and creating a training protocol to accurately capture these voices throughout the tour. The audio was captured in multichannel using ambisonic mics, lavalier mics, and a four-channel surround – not only to have really great audio that we can play back in the gallery, but also for the model itself. We can then create many different mixes from all of these channels and then create more data for an even more high-fidelity model.

The songbook created can then be used by other people to train their own models. So really thinking about the full range of things necessary to train an AI model fairly and openly has been a big part of the project. The reason we describe it as a protocol is that this is something that can be picked up and taken by others.

The concept of ‘call and response’ plays a big role in this exhibition. Why did you choose this as a framework?

Singing practices such as call and response have helped to build spaces and structures for gathering, processing and transmitting information. Group singing is one of our oldest coordination technologies and we wanted to take inspiration for the show to explore what new protocols we want to nurture for the newest of our coordination technologies, AI. We are inspired by the UK’s rich choral tradition, putting out a call to invite choirs across the country to perform music from a new songbook that contains musical exercise and hymns that we specially developed for the purpose of training the AI model to synthesize the sound of a choir singing.

With audience participation being a key element, how do you think involving the public in these choral models impacts their perception of AI?

Choirs, and many religious practices, serve a convening role for people to check in with one another and discuss matters. The hope is that by showing all steps of the model creation process people become more curious about the field. The training recordings served the purpose of capturing voices for the model, but also became nice opportunities to speak about how people feel about these new developments.

Your work positions AI as a tool for empowerment rather than extraction. How do you see artists maintaining control and agency over their work in an AI-driven world?

We started a company with some friends to address this matter, and will have some open models this year to help people take more control over their work and identity in this new landscape. We follow the principle we invented with Holly+, where artists should encourage people to build on their work and identity, but do so by offering their own models and protocols for interacting with them. It will soon not be strange to interact with a consenting model of someone.

How do you see AI influencing or reshaping art/art making in the future?

We think AI is a bigger deal than the internet, but it is hard to make specific predictions. What we can say is that it is unlikely our media environments or habits will stay the same, and so now is a great time for artists to get involved in imagining different ways to make and share art, and themselves, with others. This is a great time for art because the future is uncertain, so there is a lot of room for artists to have ideas.

The Call is on view at At Serpentine North until 2 February 2025