In conversation with the artist Julio Le Parc and curator Reiko Setsuda

2021. Bathed in the bright summer sunshine of Ginza, a 45-metre high transparent valley composed of 15,000 45-cm square glass blocks produces 14 vivid colours, making a path from the asphalt road to the blue sky above the city. It is like Tokyo has been blessed by a huge rainbow, like a great eye gazes at the people passing by, a monument symbolising the distance, time, and spiritual journey of human life.

The 1974 work is “La Longue Marche” by Paris-based artist Julio Le Parc (born in Argentina), drawn out on the facade of the Ginza Maison Hermès on an unprecedented scale. The Fondation d’entreprise Hermès recently held an exhibition titled “Les Couleurs en Jeu (Attempts and Colours)”, focusing on the theme of “Les Couleurs (The Colours)”, among Le Parc’s artistic activities to date.

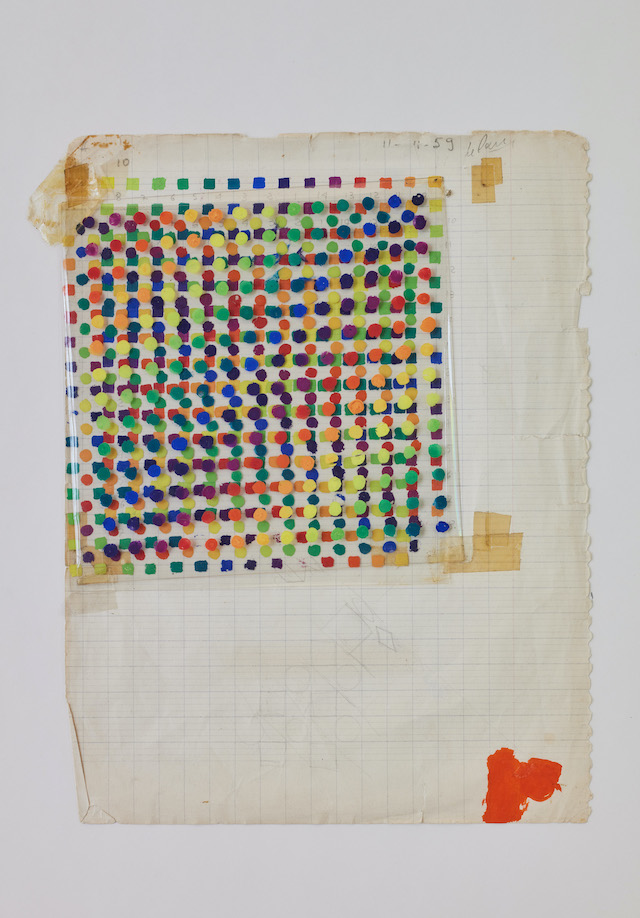

The rigour and purity of the 14 colours are aligned in space, while forming a variety of two-dimensional and three-dimensional forms. The 14 colours selected by Le Parc’s meticulous and mathematical sensibility are irreplaceable, each with its own individuality, and no colours are mixed with one another. These 14 colours are representative of all colours, and he treats them as strictly as he defines geometry in his work. This is the attitude that he has maintained for 70 years.

For Le Parc, ‘colour’ is not only a means of expression. “Colour is certainly an important element,” he states, “but in the process of creation, experience, light, movement, sound, environment, the viewer, and other elements overlap and interact, and it is then that the potential of colour comes into play and becomes an important element.”

We talked to Le Parc and Reiko Setsuda, the curator of The Fondation d’entreprise Hermès, to explore how his artistic practice reaches out to people, and the chemical reaction of his Hermès exhibition.

What is the philosophy behind The Fondation d’entreprise Hermès?

Reiko Setsuda (RS): The Fondation d’entreprise Hermès, in its support of contemporary art, does not have a collection, but is committed to being close to its creation. All works belong to the artists. Inheriting the spirit and generosity of the Maison, which is deeply involved in the arts, it provides opportunities for encounters with a variety of art in a way that is different from museums that focus on collecting.

The space is open to all, so that everyone can take home an ‘experience’. I thought that this spirit could be considered to be in line with Le Parc’s awareness of the issues of his activities. In an interview, Le Parc said that the ‘wall’ he felt as a child due to social disparity was one of his starting points, which later developed into his activities to question society as an open experience of art.

Julio Le Parc (JP): When I was a child, in front of my house there was a wall. The construction workers for the railroad, the working class, lived on this side. On the other side, there was a community of British people who owned the railroad. The disparity, inequality, domination, the ruling class rising above the rest, the monopoly of wealth (which is created by the labour of many), and the exploitation of the poor that I would later see in society was the world I experienced as a child. Art is valued by a handful of people, the wealthy. They are the ‘people on the other side of the wall’.

RS: Le Parc’s works are not completed in his studio or in the exhibition space. It is an attempt to create an interaction between the work and people, and the environment. Through this exhibition, I thought that a new relationship and interaction could develop between the people and the city, here in Tokyo. “La Longue Marche” draws an organic line, seamlessly connecting the everyday life of the streets and intersections to the architecture and space, both physically and cognitively.

Tell us about the meaning behind the exhibition’s title

RS: When I thought about how to present the ‘colour’ works that were the subject of the exhibition, I saw how Le Parc embeds in ‘colour’ his questions towards the political nature of art, which surfaces in his work as the spirit of experimentation in the form of struggle, scheming, and playfulness. In the title of this exhibition, Les Couleurs en Jeu, ‘en Jeu’ has the meaning of ‘play’ or ‘gambling’ as well as ‘political scheme (enjeu)’.

Julio, in the late 1960s, you threw yourself into political movements, interrogating the fact that art was appreciated only by limited people and that viewers remained in a passive position. One activity that expressed this wish for participation was a program called “Day in the Street”, which you organised with the Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel (GRAV) group 1966.

JP: The point of our attempt was not to popularise art, or to simply exhibit works, or to teach or instruct the audience anything. It is important to have the experience of working directly with people on the street and allow them to invent for themselves what they should be doing. People have the ability to appreciate art naturally and they participated and intervened. Excessive praise of art in galleries and museums is deceptive. The people on the street are not inferior to the exhibits, but they are equal to the ‘experience’ we propose.

What is the exhibition method you adopted to express this experience?

RS: To some of those who defended a more political practice, GRAV’s attempt was not properly appreciated. But instead of targeting only the elite, the dissidents, and the leftist bourgeois, Le Parc’s attempt to open up to the public and involve them as viewers was undoubtedly a political experiment and intervention through ‘play’.

In order to express his spirit and his resistance to the authority of art, we did not include any commentary or explanation in this exhibition, and we did not make it a retrospective, so that viewers could enjoy it freely and lightly. For example, we do not indicate anything about how to engage with Le Parc’s “Lames réfléchissantes”. It is left up to the viewers to find their own relationship with it.

How did you and Julio work together to create this exhibition?

RS: Le Parc emphasises that ‘art work should be connected to the city’. The space of the Ginza Maison Hermès is the opposite of the usual white cube space, and therefore any exhibition conceived in this space becomes site-specific from the very beginning. The philosophy of the architect Renzo Piano, the glass blocks, and the penetrating neon lights of Ginza are so unique that the space could already be a work of art in itself.

How to confront and approach this space has always been a matter of deep interest for artists. This time, in addition to the space where the city intervenes by passing through the glass blocks, the motif of the facade work also intervenes in the room, which overlaps with Le Parc’s thought process. It took four months to match ‘the colour sheet’ for the facade work. It was a very rigorous selection process, with about 20 different colour candidates for each one. In Le Parc’s work, even the slightest change in the 14 colours he originally defined is equivalent to changing the geometric form. The colours he has defined can only be chosen by him.

By collaborating with Le Parc, I now understand his rigorous attention to detail. The two works on the facade are “La Longue Marche” and “Série 14 – 2 Cercles fractionnés”. Both use exactly the same 14 colours, but the optical illusion will make you think that they are gradations of different hues. I think that this optical effect could only have been achieved by the strictly defined 14 colours and patterns that have been derived from his own calculations and experiments since the beginning of his practice.

Initially, we had planned to have one facade work, but as the seasons changed and the light of autumn became softer, we thought it would be interesting to exhibit another work with strong geometric elements which would stand out in this new angle of light. “La Longue Marche” installed in the elevator shaft also has horizontal grid lines added at the request of Le Parc. As the viewer moves up and down, the speed of the ascending and descending elevator is added to the visual perception, and the grid lines mark a new scale. I could have exhibited the series of works from “La Longue Marche” statically in the gallery space, but by showing them in an elevator, the scale changes, and the visual and intellectual impressions change dramatically. I felt that his playfulness was lively there.

Le Parc visited Tokyo in the latter half of the exhibition period. When he saw this exhibition, he was very pleased. He said that it was beyond his imagination.

What do you aim to achieve through the activity of art?

JP: My work is completed through the experience of the viewer. They create a relationship between themselves and the work without any explanation from the artist. This is the best kind of interaction. It does not matter the knowledge of art history, education, or sensitivity. I believe it is possible for any person to create a relationship with the artwork in any way. They go beyond being the viewer and become the protagonist of the work, scene, or story.

To experience is to focus on ‘possibility’, ‘development’, and ‘transcendence of discipline’. These are brought by the relationship with the viewer, and it is very important to know what the viewer is interested in. The influence of these relationships may be small, but they all lead to the viewer’s optimism. Optimism is a positive way of thinking, not only about art, but also about people. Looking back at GRAV’s “Day in the street”, the relationship between our approach and people was natural and spontaneous. It’s not a hard theory, nor the kind of relationship that is created at events such as opening receptions. Bringing optimism into their lives has been an important experience for me, and it might be my destination.

And, specifically with this exhibition?

JP: It is composed of elements questioning the meaning of exhibiting in Japan and what Hermès stands for in this country. There is a facade, an elevator, and a window display. I think the exhibition is open to the city and visitors in a multi-layered way. There are people who take the elevator up to the 8th floor gallery to see the exhibition, and people who see from the ground. I felt that there is a possibility of direct encounters with various people who make different choices.

As for the facade work, wouldn’t it be good to interview people on the street to see what kind of interest they have in it? If you haven’t done so yet, please try (laughs). I think their answers will become the profile of this work. It was the first time for me to create the work on a huge scale without limitations, and it was truly a wonderful experience. Because it was the birth of a new existence in the city. I can’t tell you how much inspiration I got from being able to express my world to the fullest. I would like to thank Hermès and Ms. Setsuda for this experience.

All photography © Nacása & Partners Inc. and courtesy of Fondation Hermès