Oliver Eglin examines the latest from Chose Commune, vintage prints from one of Japans finest

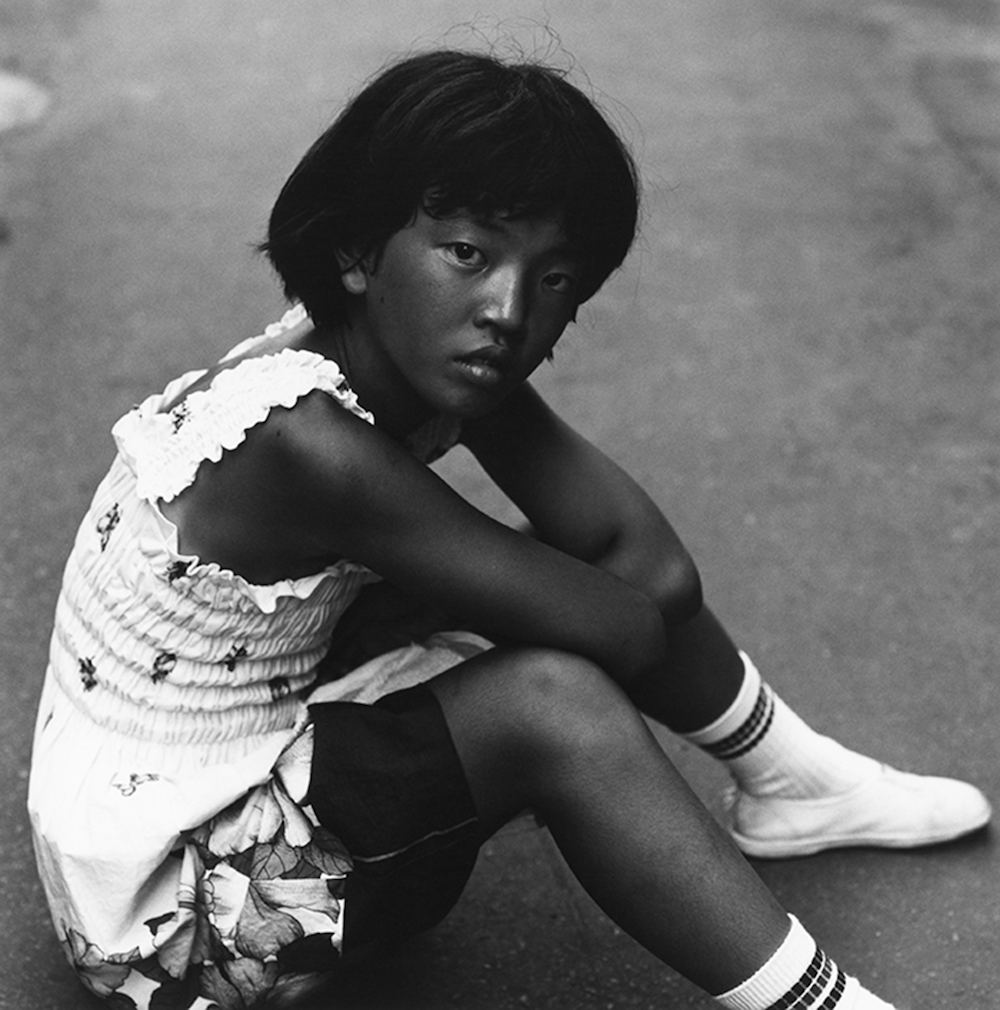

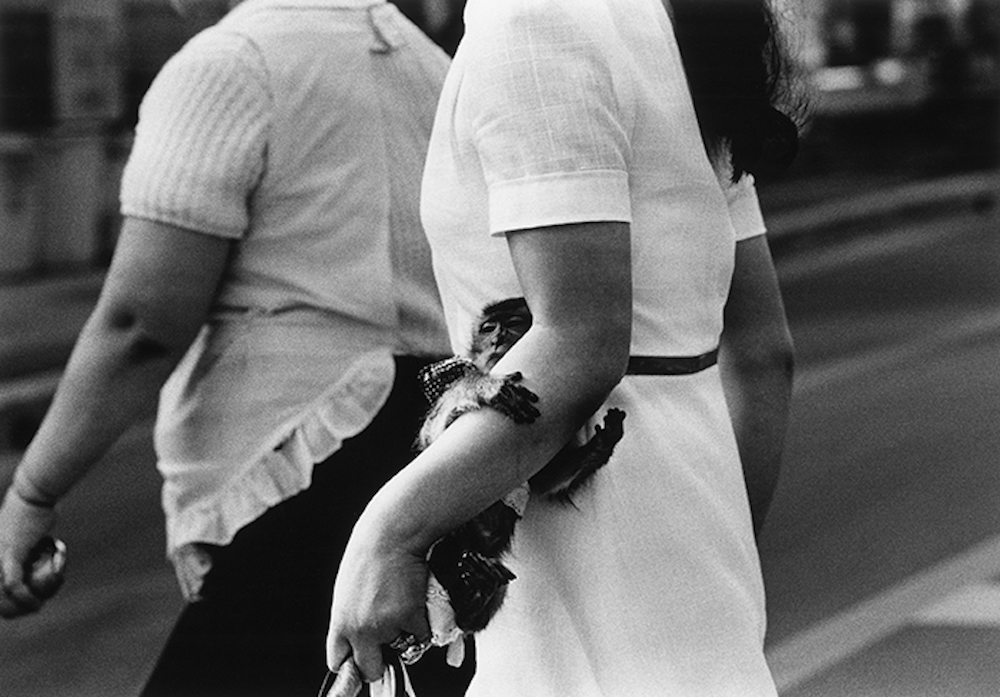

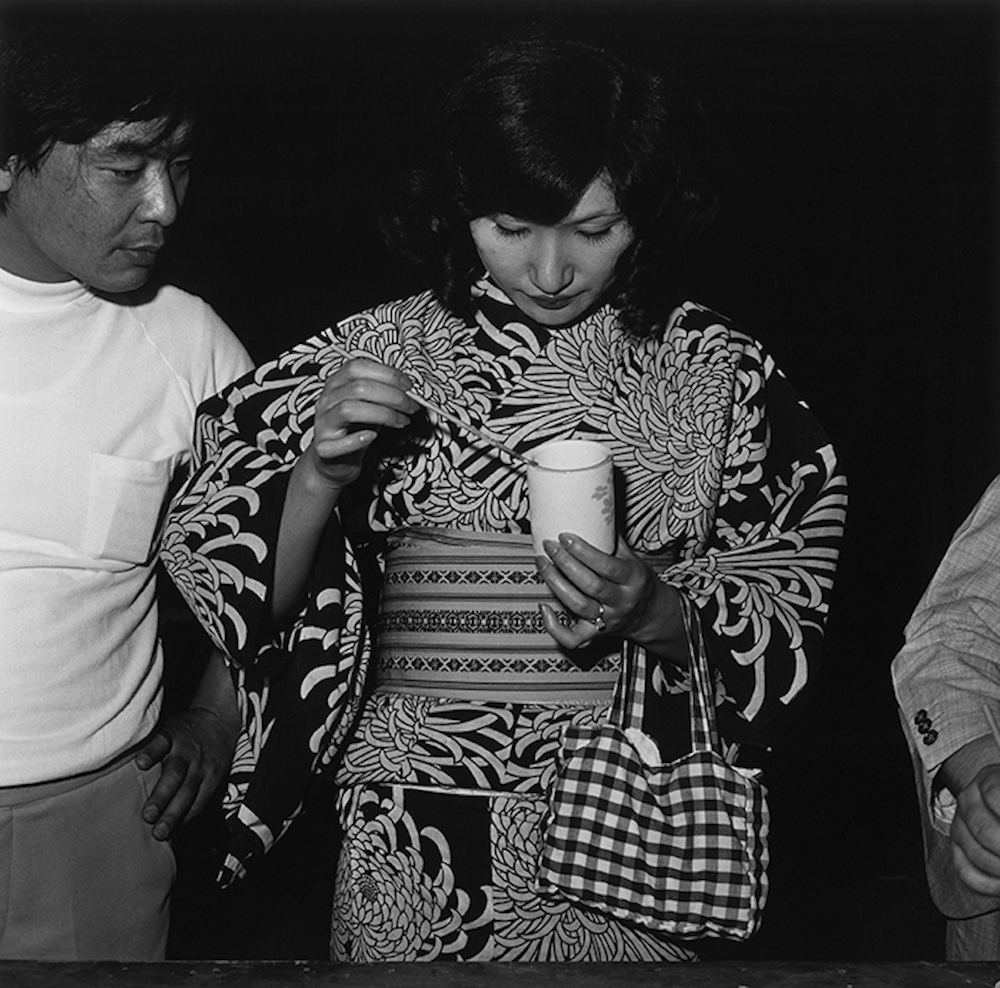

78, a new title from Marseille-based publisher Chose Commune, compiles a selection of images from the archive of Japanese photographer Issei Suda. Meandering through the streets of 1970s Tokyo and its surrounding prefectures, the book comprises of seventy-eight vintage prints. Released posthumously this eclectic compendium includes works that were mostly unpublished in his lifetime. Hard to pin down to any particular theme, Suda’s photographs are unified by a sense of innate curiosity and wit. The book flows elegantly from fleeting scenes of the street to quieter and more intimate moments and gives an insight into the unique vision of one of Japan’s lesser-known photographers.

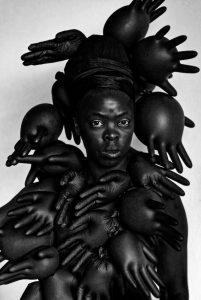

There is a touch of surrealism to Suda’s best work. Flicking through the book I often lingered in puzzlement trying to unravel an image. A photograph of what seems to be a business lunch of some sort appears as a tangle of Escher-like hands. With their faces obscured, the men’s dislocated limbs swirl together in mystifying geometry, each one grasping at a cup, glass or teapot. Suda revels in such abstraction and his works are both beguiling and beautiful.

The tonality of Suda’s monochrome prints has a delicate touch, diverging from the more contrasty aesthetic favoured by contemporaries such as Daidō Moriyama and Shōmei Tōmatsu. His distribution of light and dark is wonderfully employed to elevate otherwise unremarkable works to scenes of great refinement. A favourite is a photograph of segments of squid hung out to dry on a rack. Looking more like the parts of a dissected alien, luminous tentacles and mantles droop with murderous portent from their wire skewers. What Walker Evans described as “the seriousness in certain small things,” in Suda’s work his eye seeks to cast extraordinary light upon scenes of the everyday. A cellophane wrap or a distressed poster are given equal prominence amongst more traditional subject matter.

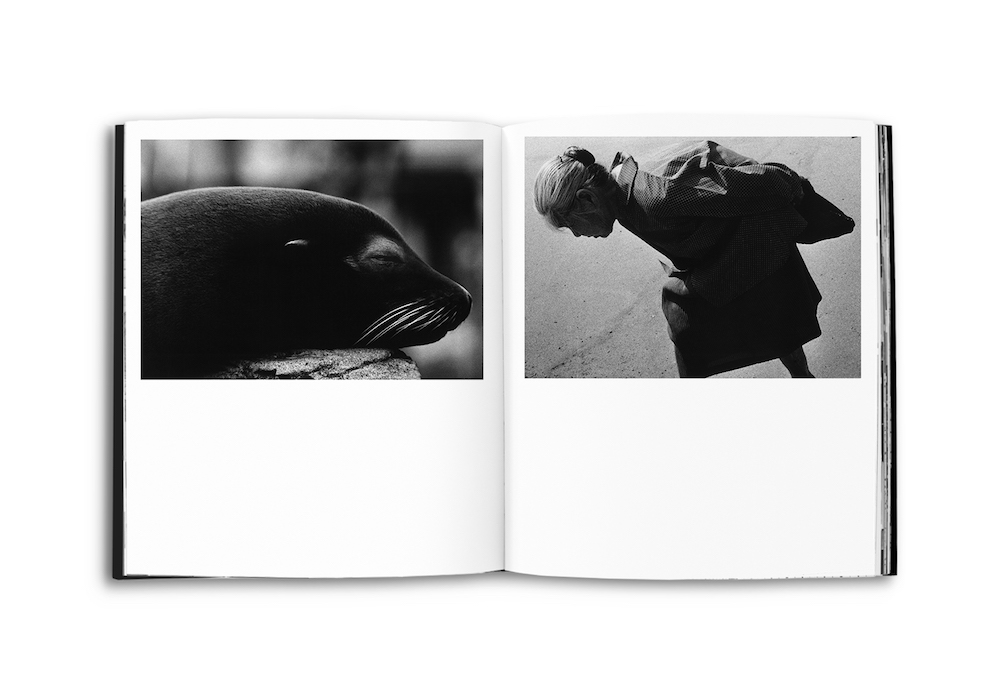

Cécile Poimboeuf-Koizumi, the book’s editor, has carefully arranged her edit with the same playful energy as is found within the images themselves. One photograph depicting the crooked frame of an old woman, is placed opposite that of a dozing sea lion. The seal’s placid expression squints back across the page to the stooped figure of the woman, their silhouettes mirroring one another, as though she too were resting her chin on an imaginary rock. These witty contrasts underscore the book’s charm, as Suda’s images resist linear progression and forge instead more poetic visual associations.

Suda’s playful use of timing is another successful trope of the work. A fedora-hatted man clutches two wine bottles stuffed with large flowers which look, at first glance, convincingly like exploding fireworks. As he struts into Suda’s frame a knowing eye winks at the photographer. A visual gag about the inertia of a photography perhaps. “Time is dead as long as it is being clicked off by little wheels” wrote William Faulkner (The Sound And The Fury), although referring to a clock, he could equally have been talking about the enduring magic of an Issei Suda’s photograph.