In Practice is a new series of conversations with artists and photographers, spotlighting what creatives are making and why – from personal histories to creative roadblocks, and the stories shaping their output today. In this first edition, photographer and director Vivek Vadoliya discusses identity, intimacy and inheritance in his most personal work to date

There are many reasons why a person might be drawn towards the medium of photography. It’s a powerful tool for documenting the world around you – to find meaning in this crazy world, to understand it better, and to showcase the variety of people and communities that live in it. For Vivek Vadoliya, a British Asian photographer and director based between London, New York and Mumbai, he picked up his camera as a way of reflecting his identity, a means of spotlighting the stories that are often untold. “Mainstream narratives often flatten or misrepresent people – especially people of colour or those from marginalised communities,” he says. “I’m interested in nuance, and showing people with complexity and care.”

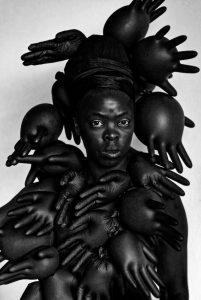

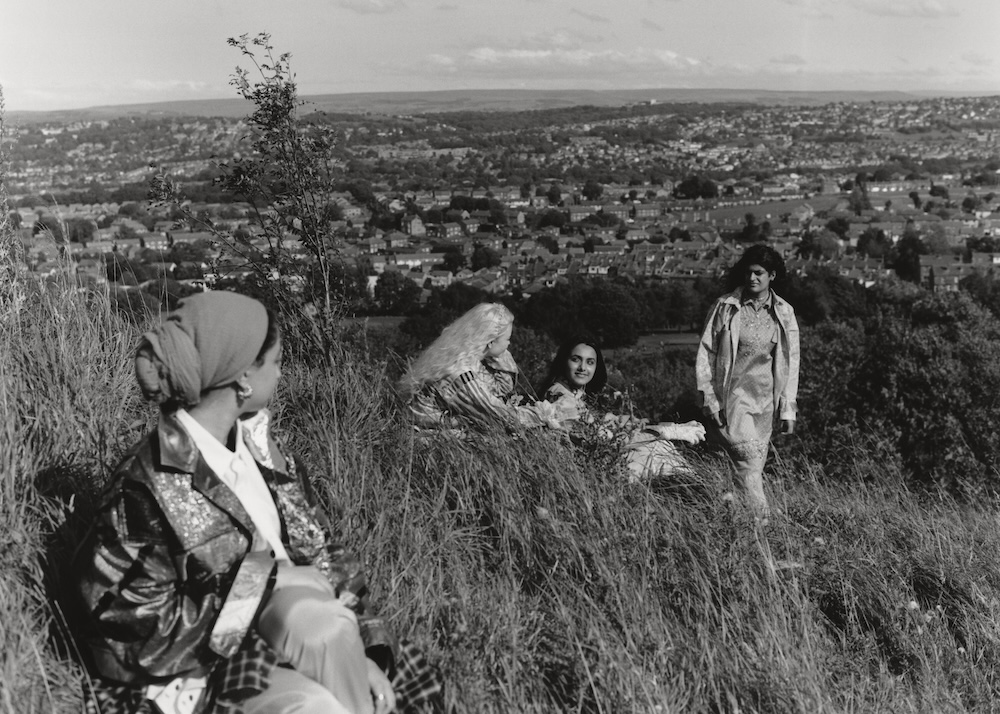

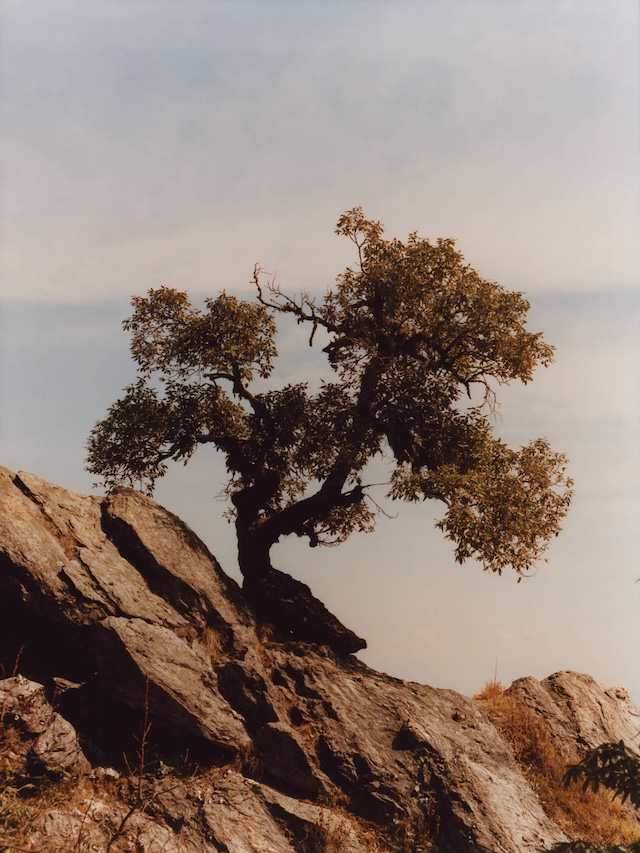

Whether it’s a series on young Muslim women in Bradford, a project exploring brotherhood in the South Asian diaspora, or turning the camera inwards on his own family, Vadoliya moves with intention and has developed a visual language that’s rooted in softness and strength. His deliciously tonal imagery, oozing with colour and texture, has the ability to both reflect the warmth and vibrancy of India – “the sensory overload you experience walking through Indian streets”, as he puts it – as well as the narratives of those who are often overlooked in British society. You can almost feel the worn foam, the dust or wind in the air – but the images are also sharp in what they reveal. Identity as something constantly negotiated; masculinity in flux; home as an emotional, migratory space.

Vadoliya’s creative journey didn’t begin with a fixed sense of authorship. He studied photography at university but spent his early career producing branded content in an industry that sharpened his eye but left little room for vulnerability. Over time, a need for change surfaced. “I felt like I had something I wanted to say,” he explains. “And I realised that the camera gave me access to spaces and communities where I could ask questions.”

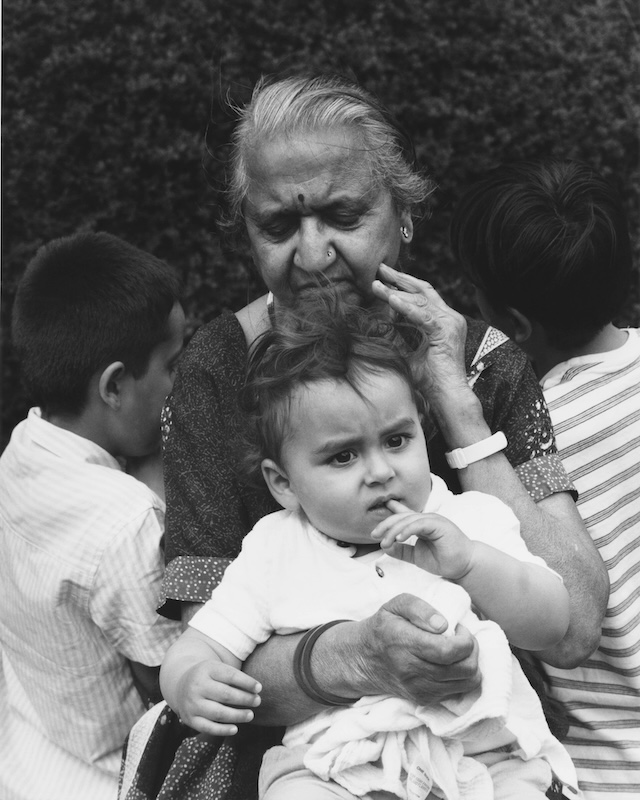

That curiosity and spirit flows through his first solo exhibition, & When the Seeds Fell, currently on view at 1014 Gallery in London. Curated by Jamie Allan Shaw, the work on show is Vadoliya’s most intimate to date, casting his own family in poetic reimaginings of classical portraiture. It examines generational care, the weight of tradition and the elasticity of cultural inheritance – how it stretches, morphs and settles between continents. “The show explores how home isn’t fixed,” he says, “it’s a moving construct, shaped by experience, migration, memory and feeling.”

But to frame Vadoliya’s practice solely through autobiography is to miss its larger reach. For years, he has been carving out a space for people, particularly those on the margins. He resists typecasting, both within his subjects and himself. “I want the freedom to connect with people outside of my immediate identity – because that’s where the most unexpected and meaningful conversations happen.”

In this conversation, Vadoliya reflects on the early parts of his practice, the challenges of navigating a creative industry that still lacks real access, and what it means to hold both the role of son and artist – with all the tension, responsibility and beauty that entails.

Can you tell me a bit about your background and how you first got into photography and film?

I studied photography at university, but after graduating I spent several years working as a producer in advertising and branded content. At that point, I didn’t have a clear idea of what I wanted to do with photography – I was experimenting. Around 2017–2018, I began to make more personal work, often centred around subjects I felt deeply connected to. I started photographing South Asian men and creating more documentary-style projects while I was living in Berlin. That’s when I realised I loved telling people’s stories through photography. The more I did it, the clearer it became that I wanted to transition fully into making work for myself. That’s when I became a full-time photographer.

What made you leave advertising and start focusing on your own creative work?

I felt like I had something I wanted to say – and I realised that the camera gave me access to spaces and communities where I could ask questions. That was something I’d done as a teenager, using photography to connect with people and understand the world around me. Over time, I found myself craving authenticity. Working on the brand side can sometimes distort your sense of reality, and I wanted to return to something more grounded and meaningful.

How have your Indian and British identities influenced your visual style and the stories you tell?

Tonally, my work is often warm, vibrant and colourful, which I think reflects my Indian heritage. The sensory overload you experience walking through Indian streets – the colours, textures and light – definitely shapes how I see. My British identity plays out more in the subject matter: I’m drawn to quieter, often overlooked narratives – people who live on the fringes. I’m interested in showing a more nuanced view of British identity, spotlighting stories that aren’t always told.

What draws you to both photography and film, and how do you decide which medium to use?

I’m drawn to both because they allow me to explore different forms of storytelling. Film gives you time and space to develop narrative, and I love the way it unfolds gradually. At the same time, photography lets me work in a more immediate, instinctual way – just me and the camera. Sometimes the story or subject calls for movement and audio; sometimes a still image says more. For me, they’re natural extensions of each other.

Your work often focuses on people and communities – how do you build trust with your subjects?

By being honest and having good conversations. For me, it always starts with listening. I show people my work, explain where I’m coming from, and build trust through connection. The image is often just the result of a meaningful exchange. What excites me most about photography is the relationship you form before the image is made.

Projects like Brotherhood, Sisterhood and Mallakhamb spotlight overlooked voices – why is that important to you?

Because I want to show the world as I see it. Mainstream narratives often flatten or misrepresent people – especially people of colour or those from marginalised communities. I’m interested in nuance, and showing people with complexity and care. Brotherhood explored the full spectrum of South Asian masculinity. Sisterhood was a joyful collaboration with young Muslim women in Bradford, celebrating their beauty and power. Bradford has often been portrayed negatively in the media, and this was about offering a different image – one rooted in pride and possibility.

Your new show, & When the Seeds Fell, feels very personal – what inspired this body of work?

It grew from a desire to understand my family more deeply. Around 2020, I was thinking a lot about structure – how we support each other as a family, what duty looks like and where identity fits into all that. At the same time, I was questioning what Britishness and Indianness meant to me, and how those ideas were shaped by both culture and history. The show explores how home isn’t fixed – it’s a moving construct, shaped by experience, migration, memory and feeling.

The show touches on themes like family, illness and care – how did you explore those visually?

Some of the images are constructed portraits that play with the aesthetics of home – soft furnishings, textiles and objects that hold emotional weight. There’s a portrait of my auntie wrapped in sculptural foam that reflects how we create protective spaces for ourselves, especially when home has been nomadic. Other images explore masculinity and tradition through visual contrasts, like two wrestlers dressed in modern sportswear and traditional attire, caught mid-struggle. There’s tension and delicacy in those poses: each man relies on the other to stay upright. I also recreated iconic art historical images, like Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother and Vermeer’s Woman Reading a Letter, with my own family members. These reinterpretations shift meaning, allowing me to centre my family within visual histories that haven’t always included us.

How has being both a son and an artist shaped the way you approached this new work?

Those roles are completely entangled. Being the eldest son comes with certain expectations, especially within more traditional frameworks. And being an artist requires a lot of vulnerability. With this project, I was carrying both: the responsibility to hold my family and the desire to express what that felt like. The work became a way to process, reflect and share things I couldn’t always say directly.

What are some challenges you’ve faced navigating the creative industry so far?

One challenge is how easily people get typecast in this industry. As an artist of colour, you’re often expected to make work only about your own community. While I love exploring those stories, I also want the freedom to connect with people outside of my immediate identity – because that’s where the most unexpected and meaningful conversations can happen. Access is another challenge. People from working-class backgrounds or communities of colour often don’t see themselves reflected in the creative industries, and that lack of visibility can make it feel impossible to find a way in. That’s changing slowly, but there’s still work to do.

You’ve spoken about redefining ideas of beauty and masculinity – how has that shaped your work?

I’m not sure I’m redefining them, but I’m trying to make space for different kinds of beauty to be seen. I love portraiture because it lets me show people with care. A big part of my work is about saying: this person is worthy of being looked at, of being celebrated. It’s about expanding the idea of who gets to be visible, desirable, powerful.

What advice would you give to younger artists trying to carve out their own path today?

Start by looking inward. Think about what you want to say and why it matters to you. That kind of clarity is magnetic – it draws people in. Don’t be afraid to fail. Experiment. Not every image has to be perfect. And most importantly: take your time. I used to rush through projects, and I’ve learned that slowing down lets the work breathe. It allows the meaning to shift as you grow.

What kind of conversations do you think we need more of in the creative world right now?

I’d love to see more openness. Right now, a lot of artists are only commissioned to document their own communities. That has value, but it can also be limiting. I think we need more bravery – more artists exploring stories that sit outside their own immediate experience, and more trust from commissioners to support that. There are so many unexpected, beautiful ways people can connect across differences. I want to see more of that.

Vivek Vadoliya’s & When the Seeds Fell is on view at 1014 Gallery until 8 August