Danielle Pender is a writer and editor, and the founder of Riposte magazine. Her work has appeared in publications including The Guardian and The New York Times. In this reflective essay for Port, she explores the complexities of returning home – how distance reshapes family bonds, and the quiet negotiations that come with reunion

For the last fifteen years I have ridden the East Coast Main Line from London to Newcastle, tracing the same miles over and over, yet arriving somewhere slightly different each time. Newcastle is home in the way that childhood places always are – embedded in muscle memory, a place you don’t have to think about to know. London is where I live now, but when I picture my family, the roots of it, I think of my mother, my brother and me.

For years it was just the three of us, tightly bound inside a small house, navigating whatever came our way. We were in each other’s pockets in that specific way small families in small houses are – you know everything about each other, whether you want to or not. Routines, rhythms, moods, silences. What time someone would come through the front door, what it meant when they didn’t. The smell of someone’s shampoo lingering in the hallway. A shifting weather system of closeness and irritation and deep, unspoken understanding.

Now, my brother and I have our own families. We have expanded, our lives have changed, and in doing so, we have also dispersed. As the train slowly pulls over the River Tyne into the station, I think of a Heraclitus quote that Siri Hustvedt included in Mothers, Fathers and Others: “In the same river we both step and do not step, we are and are not”. A line that feels made for those who leave home and return – not as prodigals, not as tourists, but as something harder to define. Insiders who have grown alien to their own past. My mother, my brother and I were once a fixed unit inside that small house; now we orbit one another, connected but no longer in sync. We are and are not.

With people moving further from where they were born, modern family life is often reduced to a handful of sanctioned gatherings – birthdays, Christmas, the odd anniversary or weekend away. But what happens in between? What happens when you are no longer part of each other’s daily lives, when the casual, unexamined intimacy disappears? We meet as guests in each other’s presence, performing the shape of family but feeling its lack. The questions we might ask a stranger – What do you do? Who do you love? What keeps you up at night? – are the very ones we avoid with each other, afraid of exposing how much we no longer know.

For the past year, I have been writing a novel about a homecoming, which has drawn me to literature that explores this experience from different angles, offering both comfort and insight. In Long Island, Colm Tóibín’s Eilis Lacey returns to Ireland and finds herself caught between past and present – who she was before she left, who she is supposed to be now. This is often the way for families coming back together; each visit becomes a delicate negotiation, a process of reacquaintance in real time.

When Eilis buys her mother new white goods for the kitchen, a gesture driven by generosity and a desire to mark herself as different, as a grown woman of means, her mother insists she doesn’t need them, leaving them as obstacles in the hallway rather than having them installed. The protest isn’t really about the appliances. It’s about control, about the unbearable proof that Eilis has formed a life outside of this house, that she is no longer someone whose choices pass through a parental filter.

Annie Ernaux writes about this change and distance with such precision – the way that home, once so familiar, can start to feel like a foreign country. In A Man’s Place, translated by Tanya Leslie, she writes about the gulf between herself and her working-class father, which widens as her education and career take her into another world. She describes the sorrow of seeing home through new eyes, of feeling both love and alienation at once.

That tension haunts so many reunions. Gwendoline Riley captures it in First Love and My Phantoms, where adult children return to parents who are both familiar and unknowable, baffling and inevitable. There’s something particularly painful about these encounters, when love starts to feel like performance, when obligation replaces ease. The gap between people who should know each other best, but somehow, don’t.

What is it like for those who stay, watching someone return – someone who looks the same but feels subtly, irrevocably changed? The returnee carries an unspoken tension, a quiet air of judgment, whether deliberate or not. Their departure was a choice, one that, however unintentionally, suggests a rejection – of this place, this way of life. Whether their world is ‘better’ or simply different, the contrast lingers, unspoken yet inescapable.

In Gwendoline Riley’s My Phantoms, the mother is a particularly heartbreaking figure, repeatedly colliding with a daughter who has come back to Manchester to care for her, but whose presence is more duty than desire. Their dynamic is fraught; her daughter observes her life with barely concealed disdain, seeing tragedy where her mother perhaps sees only routine or comfort. The book forces the reader into an uncomfortable complicity, recognising the sharp edge of judgment in the daughter’s perspective and perhaps, uncomfortably, in their own.

But estrangement is not inevitable. In Close to Home, Michael Magee’s protagonist Sean returns to Belfast after studying at university in Liverpool, finding his brother and old friends caught in a different rhythm – one shaped by economic precarity and cycles of drink and drugs. The distance between them is undeniable, but love does not demand sameness. Magee writes these relationships with a deep, unflinching tenderness, recognising that while family bonds may stretch, they do not always break.

In the novel’s final moments, Sean stands with his older brother, Anthony – a man hardened by experience, shaped by a trauma that could have driven them apart. Instead, Magee offers a scene so quietly devastating, so full of unspoken understanding, that it brings me to tears every time I read it:

“I tried to get away from him, but he was stronger than me and he wasn’t letting go. Get off, I said, and he giggled and kissed me on the ear and on the side of the head, my face, my neck and anywhere he could reach with his arm around me. And while he did this he told me he loved me. I love you to death, he said, and he kissed me and kissed me.”

The places and people we come from remain woven into us, no matter how far we go. Family holds a version of us that is fundamental and inescapable – the ones who knew us before we knew ourselves. We may no longer share the details of our daily lives, but that early imprint lingers, shaping us in ways we can’t always see. Whether that is a comfort or a source of pain depends on the circumstances. As Didier Eribon writes in Returning to Reims, “Whatever you have uprooted yourself from still endures as an integral part of who you are.”

For my mother, my brother and me, it is something I cherish. We witnessed everything that shaped us, and in that shared history, there is an unspoken understanding of how the past made us who we are today, no matter what other factors have influenced our identity. I will always be deeply grateful for that. I find solace in the sayings we still repeat, the in-jokes that need no explanation, the memories that resurface without warning – and the way we all look the same when we laugh.

I think about this as I walk across London Bridge one evening after work, caught by a deep and unexpected longing – not for Newcastle itself, but for the version of us that once lived there. My mother, my brother and me in her bedroom, playing charades, doing handstands onto her bed, laughing ourselves breathless. The physical closeness of it. The certainty that we belonged to each other. That incarnation of us is gone, but something remains, changed but intact. Like the body maintaining homeostasis, making constant adjustments to keep itself, itself.

To leave home is to fracture a wholeness you can never fully restore. But maybe restoration isn’t the point. Family is not static. It is movement – towards, away and back again.

We are and are not, but still, some of us return.

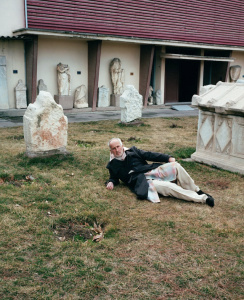

Illustration by Alec Doherty

This article is taken from Port issue 36. To continue reading, buy the issue or subscribe head here