As machines continue to shape our world, what will become of the role of the artist? In light of a new exhibition at Tate Modern, we explore how artists continue to adapt and create sensory experiences that reflect the human condition

In his 1972 bestseller Ways of Seeing, John Berger explored how the invention of the camera changed the way people viewed art. His work underlined how different technologies hold the capacity to alter our perception of the world and our experience of it. This autumn, the Tate Modern presents an expansive new exhibition, Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet curated by Val Ravaglia, which lays out the landscape of innovation across optical, kinetic, programmed, and digital art that has paved the way for our present day.

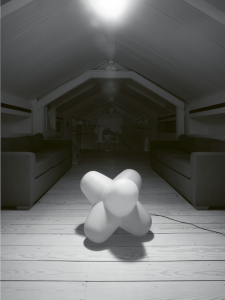

In the aftermath of the Second World War, the desire for regeneration in the 1950s was strong, and artistic groups such as ZERO sprang from the ashes of destruction. Founded by Heinz Mack and Otto Piene, ZERO was about starting over with a focus on using new media and materials, repurposing mediums like metal and light, and using them for non-utilitarian means. In Piene’s various ‘light ballets,’ the German artist surrounds viewers in a continuous orchestration to create new sensory experiences. “We want to exhibit in the sky,” he wrote, “not in order to establish there a new art world, but rather to enter new space peacefully – that is, freely, playfully and actively, not as slaves of war technology.” Artist collectives were eager to rewrite the rules; in the Netherlands, it was the Nul Group, and in Japan, it was the Gutai, an avant-garde group daring to go beyond traditional notions of art. As Japan grappled with the modernization of electricity, Gutai member Atsuko Tanaka took this tension and played it out over her own body. In Electric Dress (1956) her face emerged from a 50kg cluster of lights suspended from the ceiling, quivering with energy, pulsating in flashes, inspired by the shimmering neon of an Osaka station pharmaceutical advert. Her body, like the landscape of her country, became unrecognizable, overwhelmed, and subsumed. For another Gutai member, Tatsuo Miyajima, his Lattice B (1990), presented a landscape over which time itself was interrogated, with an eight-metre-long wall installation of flashing LED lights providing the unseen element with a witnessable rhythm.

While technologies can provide the means of developing new visual languages, they can also appear fully formed. British artist Suzanne Treister deployed the aesthetics of early computer games and made them her own. Inspired by impatiently waiting for her boyfriend to finish playing at amusement arcades, she created Fictional Videogame Stills (1991–92) to explore larger questions about life and society: “I wasn’t particularly seduced by video games or computers at the time,” she penned in her essay, ‘Videogames and Art’, “but I felt I had to deal with them as they were not going to go away.” Similarly, Palestinian-American artist Samia Halaby was already an accomplished abstract painter when she purchased an Amiga 1000 computer in the mid-1980s and taught herself how to code, creating mesmerising abstract digital animations that would become known as her ‘kinetic paintings.’

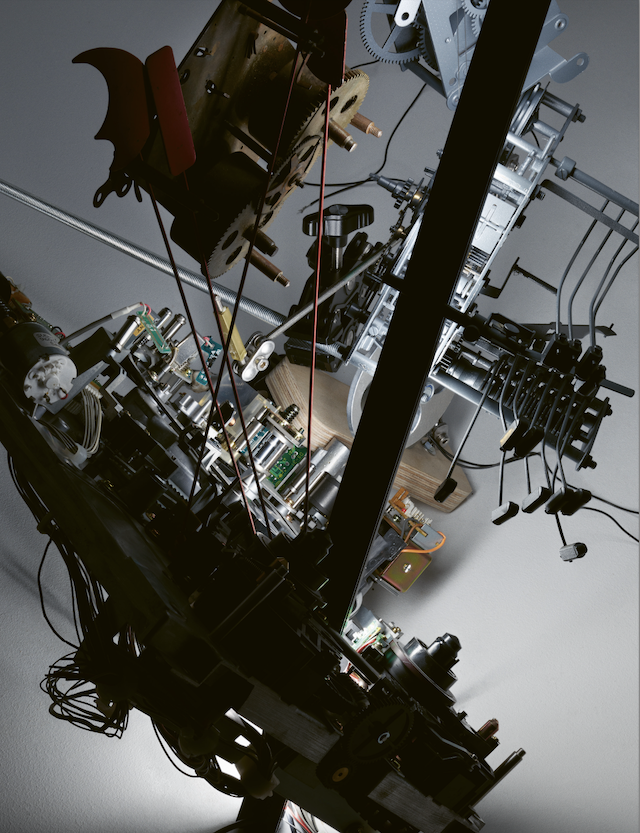

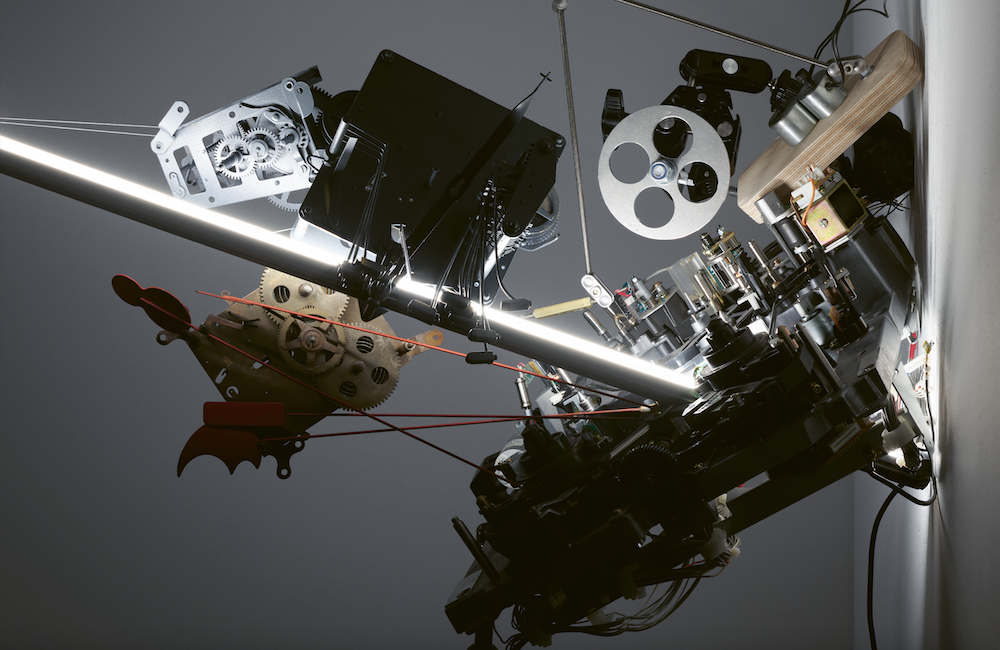

Art often requires experimentation and invention, a curiosity that impels the discovery and creation of something new. Yet artists aren’t simply co-opting technologies; at times, they’ve also been the ones inventing them. Setting aside the likes of Da Vinci, we can look to the British-Canadian artist Brion Gysin, whose homemade mechanical device, Dreamachine no.9 (1960–76), creates captivating kaleidoscopic patterns, or the American artist Rebecca Allen, who developed cutting-edge motion-capture and 3D modeling techniques in the 1980s.

As technology becomes more integrated into our lives, the vital power of the artist in identifying and questioning its role has become ever more important as technology evolves. Berger’s bestseller was ruminating on ideas that had already been articulated by Walter Benjamin in The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (1935). The anxiety of AI now provides similar fodder. “People underestimate just how flexible human creativity is,” Ravaglia notes. “There is a tendency to forget that the debates on machines making artists redundant is at least as old as the invention of photography… but creativity simply adapted to the conditions of image-making in the age of mechanical reproduction, and artists will no doubt continue to find ways to articulate new languages through new technological media.”

Before photography, Berger outlines, art had always existed within a physical space, “a place, in which, or for which, the work was made,” and thus the experience of art itself had been one of ritual “set apart from the rest of life.” It is interesting to note how many artists who harness new technologies now seek to create this same transient physical experience. Rather than a painting that can be photographed and photocopied, instead the emphasis becomes on the ephemeral nature of experience itself, the irreproducible identity of time: the effect of a light dancing upon a wall; the ripples of a portrait in a digital pool; a flash of electricity. It is precisely in the evasiveness of art – the ability of technologies to recreate a sense of awe and true situated experience – where we find the raw feeling of humanity and mortality reignited. In its mechanised methodology, technology ironically cannot help but underscore how artworks are activated by their creator and later their audiences, lying dormant until a witness comes to complete them. After all, without the beating heart, that human electricity, those excitable ions that form life itself, there would be no art at all.

Photography Dan Tobin Smith

This article is taken from Port Issue 35. To continue reading, buy the issue or subscribe here