Art history has long celebrated male artists while overlooking women’s contributions. The Guggenheim Bilbao’s exhibition of Hilma af Klint’s revolutionary work is a crucial step in rebalancing the narrative

In 1971, Linda Nochlin asked: “Why have there been no great women artists?” Nochlin argued that greatness has long been seen as the domain of so-called ‘geniuses’ – almost always white, male and privileged – while women were held back by structural barriers. Denied formal training and entry into male-dominated guilds, women artists were excluded from art’s major institutions and, consequently, from history itself. While the question itself is flawed, it remains strikingly relevant today, with institutions beginning to confront these historical exclusions.

Over centuries, patriarchal norms confined women to domestic roles, limiting their ability to pursue art professionally. Even when women were able to study art, they were often restricted to subjects deemed appropriate for their gender, such as portraiture or still life, rather than grand historical or monumental works. Art academies, galleries and museums – spaces where an artist’s career could flourish – were also controlled by men. Women’s work was rarely exhibited, and they were excluded from major competitions and commissions. Additionally, art criticism and scholarship were, and in many ways still are, dominated by men. These gatekeepers shaped art history by documenting and celebrating the work of male artists, while ignoring or downplaying the contributions of women.

Even when women did achieve some level of recognition during their lifetimes, their work was often neglected in archives and historical accounts. Artemisia Gentileschi was an acclaimed Baroque painter whose powerful work reflected a distinctly female perspective. Yet, her contributions were largely forgotten for centuries. And Judith Leyster, a Dutch Golden Age painter, was also overshadowed by her male contemporaries.

The rediscovery of women artists began in the late 20th century, with scholars and curators working to reclaim the lost legacies of these women. The feminist art movement of the 1960s and 70s was also crucial in highlighting the achievements of artists like Lee Krasner, who was often overshadowed by her husband, Jackson Pollock, despite her significant contributions to Abstract Expressionism. And one of the most significant rediscoveries is Hilma af Klint. Her abstract works, created years before those of Kandinsky and Mondrian, were dismissed during her lifetime due to a combination of societal norms and her own secrecy about her art. af Klint was deeply influenced by spiritualism, and she believed her work was meant for future generations, instructing that much of it remain unseen for 20 years after her death. By the time her paintings were revealed, the narrative of modern abstraction had already been written, and male artists were credited as its pioneers.

Despite her groundbreaking work, the patriarchal structures of the art world kept her contributions in the shadows. It wasn’t until much later, with the growing influence of feminist art historians, that af Klint’s work began to receive recognition. Her major retrospective at New York’s Guggenheim Museum in 2018, Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future, was a landmark in rewriting art history to include her contributions. And today, af Klint’s work continues to gain traction, with exhibitions around the world showcasing her as a pivotal figure in the development of abstract art. The most recent exhibition at the Guggenheim Bilbao, curated by Lucía Agirre and Tracey Bashkoff, presents her as a pioneer who predated many male modernists, evidenced through the most comprehensive study of af Klint’s oeuvre to date. As the museum’s director Juan Ignacio Vidarte said at the show’s press conference, the show is a “recovery” of the artist, and an effort in “placing her where she should be: as a trailblazer of modern extraction”.

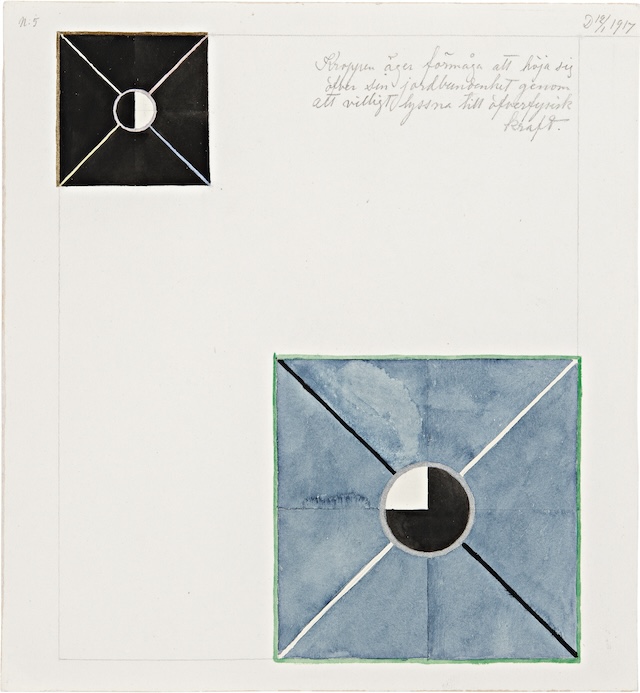

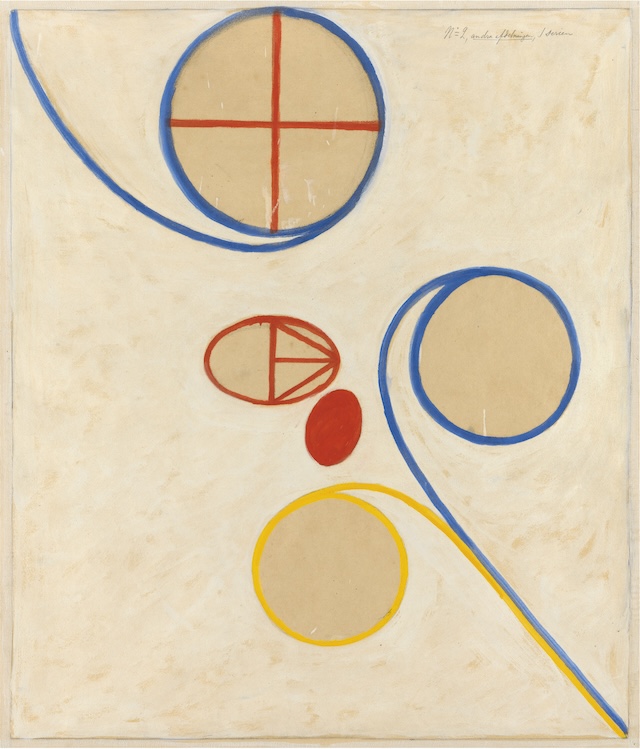

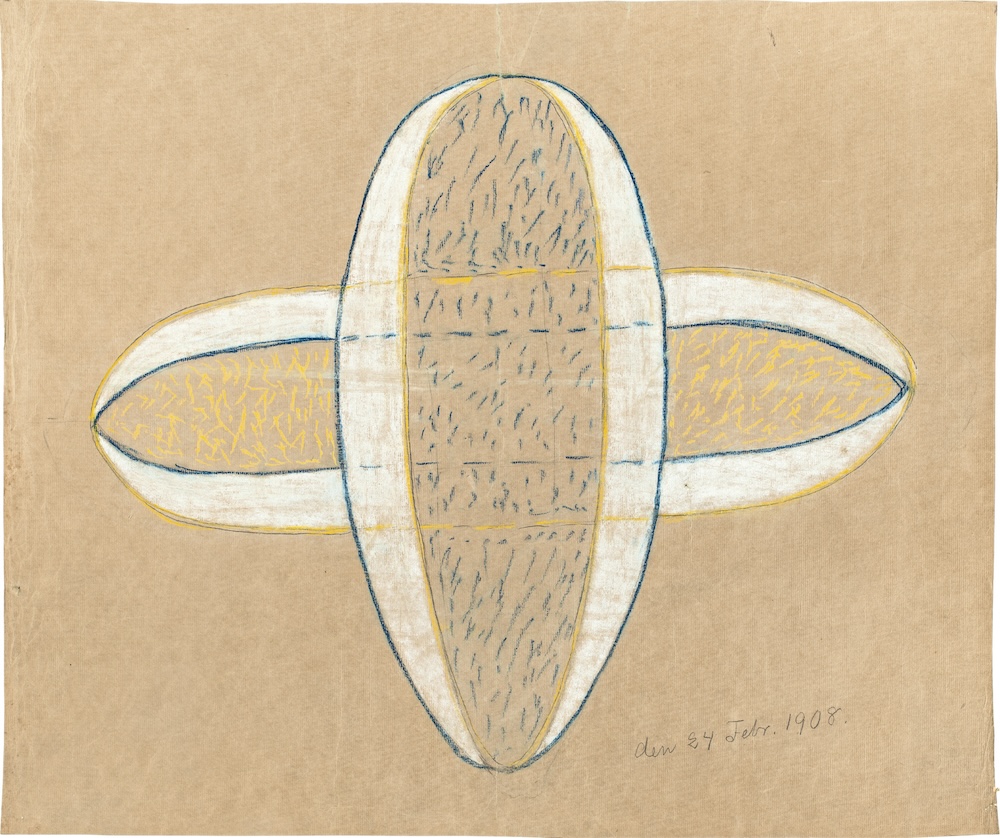

The show is also revealing new insights through previously unseen letters, journals and drawings, which help decode the complex symbolism in her work. Much was influenced by her background in mathematics, cartography and her deep spiritual beliefs. “af Klint also left behind hundreds of notebooks in which she meticulously documented her work,” said Agirre. “These notebooks are like dictionaries, helping us decode the meaning behind her symbols and letters. With a background in mathematics and cartography, her works can be seen as elaborate maps of spiritual journeys. There is still much to uncover and understand about af Klint’s work, making it continually fresh and groundbreaking even after all these years.”

One such discovery is the story of how af Klint met with Rudolf Steiner in 1908, the leader of the Theosophical Society in Germany, who af Klint thought of as the most prominent spiritual leaders of the time. He was lecturing in Stockholm and af Klint invited him to see her paintings, hoping for some positive feedback. Only he didn’t understand her work, advising that ‘no one must see this for 50 years’. It’s been recorded that this is what caused af Klint to pause her practice until she returned in 1915. However, according to the new letters on display in Guggenheim Bilbao, this meeting happened two years later than previously mentioned. She in fact stopped working before then, making this point in history obsolete. “There were many reasons for this break, including the dissolution of her group The Five, her mother going blind, and moving house. While Steiner’s visit might have affected her, it wasn’t the direct cause of her pause,” said Agirre.

There are many more notable discoveries to be found throughout this exhibition. As you enter, you’re immediately met with her early automatic drawings which she made with The Five. This group of women were from spiritualist and suffragist circles – Anna Cassel, Cornelia Cederberg, Sigrid Hedman and Mathilda Nilsson – they’d practise weekly séances and would work collaboratively – “which gave women a greater voice,” said Agirre. “While some automatic drawings were done in collaboration, with other women present during séances, af Klint herself held the pencil in most cases. We believe the works are primarily hers, but collaboration certainly played a role in the process. If this were a male artist, we might not even be asking these questions.”

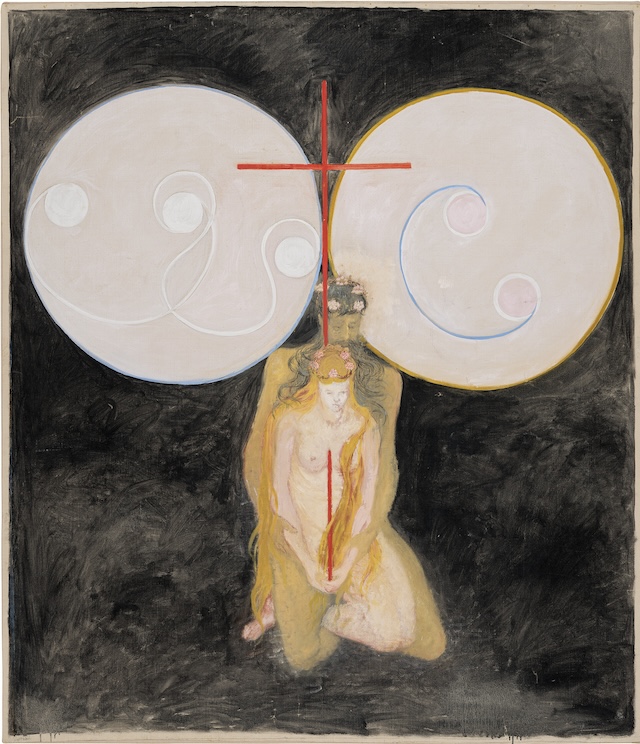

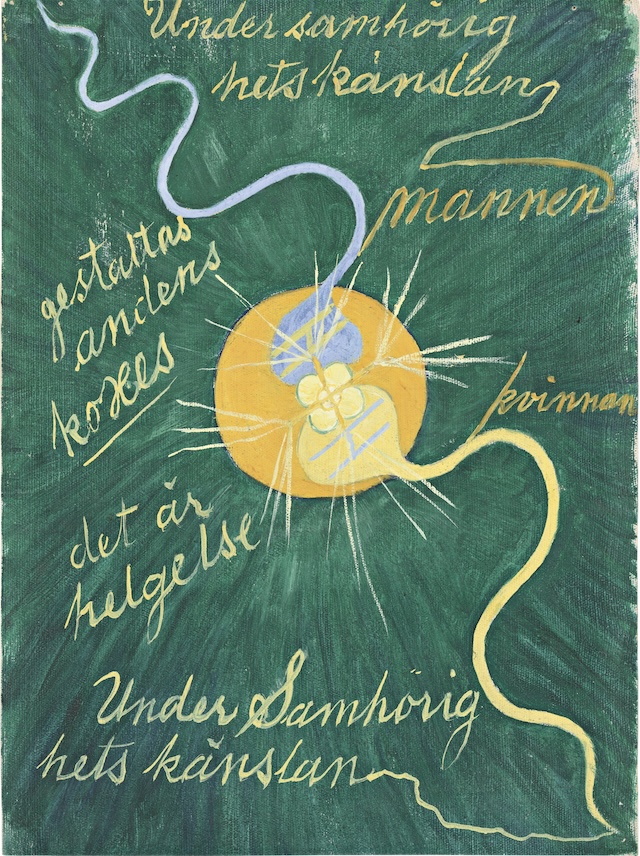

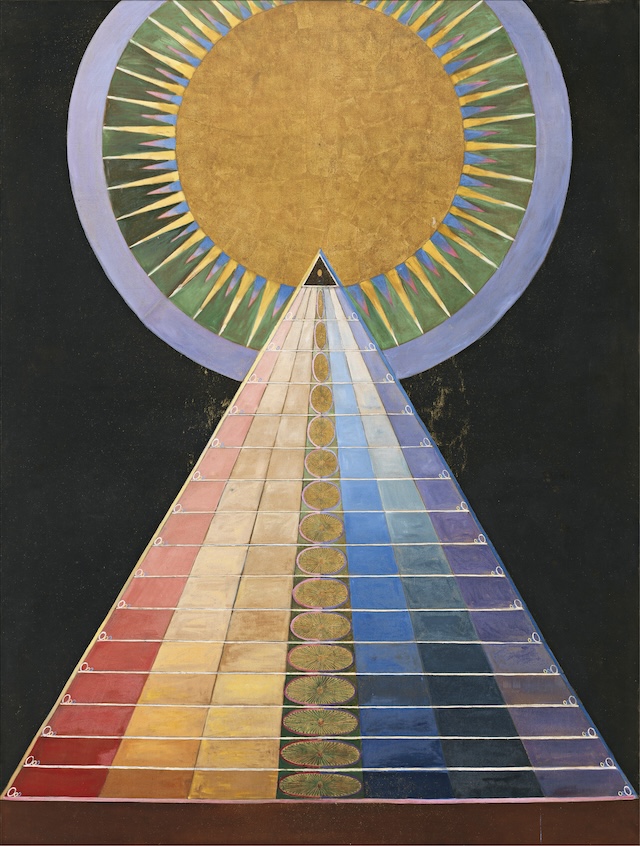

Next, viewers will observe the Paintings for the Temple series, which began in 1917 (or potentially later) and comprises a total of 193 paintings, drawings and sub-series informed by her relationship to the spiritual world (more on this series can be found here). Deeply influenced by Theosophy (she was a member of the Swedish Lodge of the Theosophical Society), af Klint believed that her works were guided by higher forces and that her role as an artist was to translate these spiritual messages into visual form, asserting unity, wholeness or holiness as the end goal – a search for a divine singularity that was lost when the world was created.

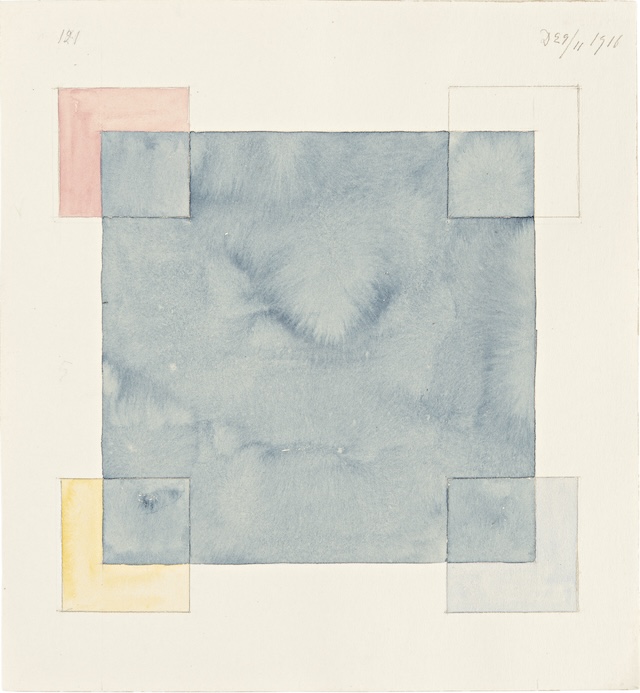

The exhibition then opens into a spacious part of the gallery showcasing her monumental sub-series, The Ten Largest, which is part of Paintings for the Temple. Here, 10 large-scale pieces that are more than 3-metres tall are lined up in a purposefully ordered fashion, exploring the stages of life through her symbolic use of colour coding. On the left, the series begins in shades of blue to represent childhood, before becoming more vivid and colourful in youth and adulthood, then finishing in washed-out shades of beige – the end of life. The swirling forms and floral motifs suggest growth and transformation, while the more rigid, abstract squares portray a sense of ageing and conclusivity. af Klint’s use of gendered symbolism becomes especially striking in this body of work, in which blue is used to represent femininity and yellow for masculinity. She’d also blend these colours to create green, a symbol of unity – a nod to her beliefs in Theosophy.

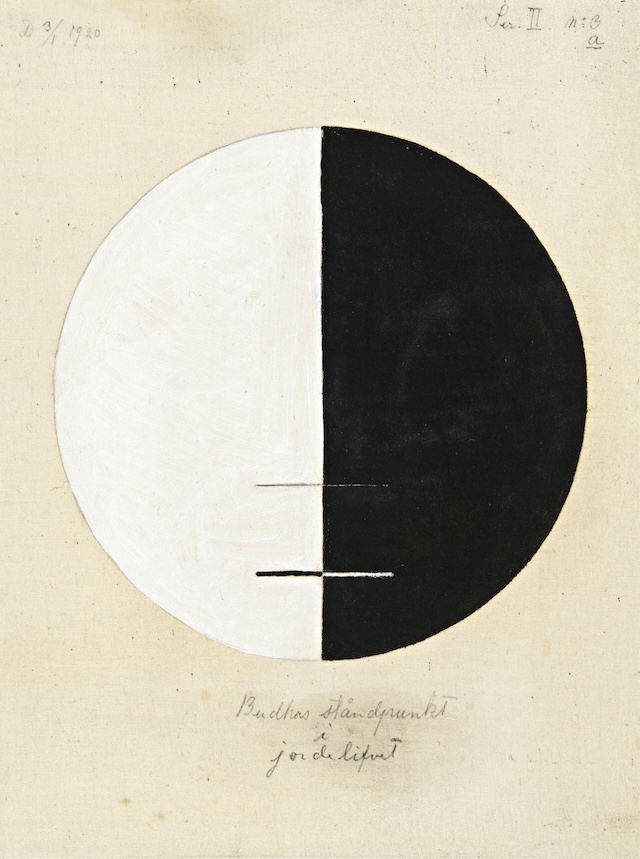

In another room, her The Swan series, which is also part of her Paintings for the Temple, af Klint presents a series of dualities – light and dark, masculine and feminine, body and spirit – through the symbol of the swan. Swans are used here to represent the process of uniting opposites, and the series progresses from more representational depictions of swans to increasingly abstract, geometric forms. In the end, they become one. Inequality obliterated.

Through colour and form. af Klint critiqued the societal limitations placed on women in the early 20th century and envisioned a world where these divisions could be eclipsed. She was utterly aware that her abstract, spiritually infused paintings were ahead of their time, both in the way of innovation and in their underlying messages about gender and connectivity. But are they ready now? We can still look to the question of “Why have there been no great women artists?” with great frustration, but there are certainly steps being made. By acknowledging these contributions to the canon, and by correcting the exclusion of women like af Klint, we can begin to provide a more inclusive account of art history. And as more women’s voices are included in the narrative, our understanding of art itself becomes richer, more diverse – and more truthful.

The Guggenheim Museum Bilbao’s Hilma af Klint exhibition is running until February 2, 2025