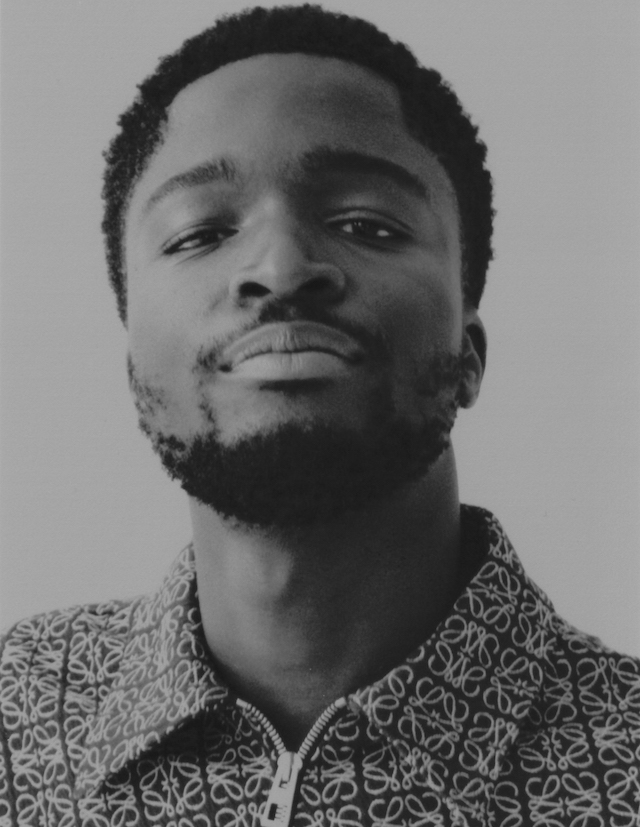

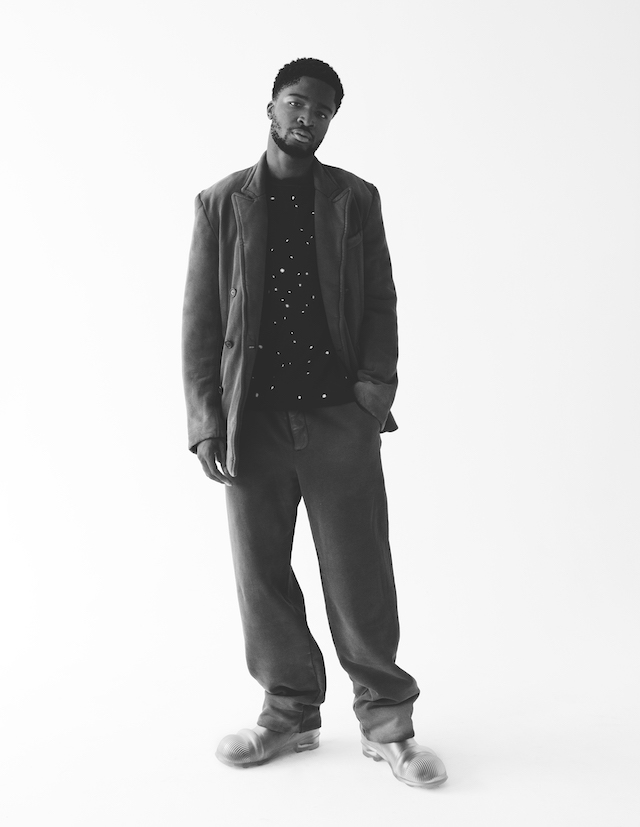

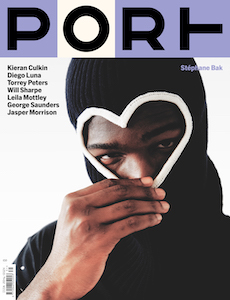

The rising French actor knows what it is to grow up fast, having been a professional stand-up comedian from the age of thirteen. Seamlessly transitioning to the big screen – with standout performances at this year’s Cannes Film Festival – the issue 31 cover star reflects on the beauty of diasporic stories and why he’s pushing for greater representation in cinema

It is 37 degrees Celsius in Paris, and Stéphane Bak is sweating. The 25-year-old actor is in his apartment and drinking grenadine with lemonade from a short rocks glass, which I mistake for a Negroni. He cackles. As it turns out, sirop is basically the French version of Ribena. “Are you drinking lean?!” a friend visiting from Toronto had asked a few weeks prior. “I was like, that’s not what I’m doing!” says Bak.

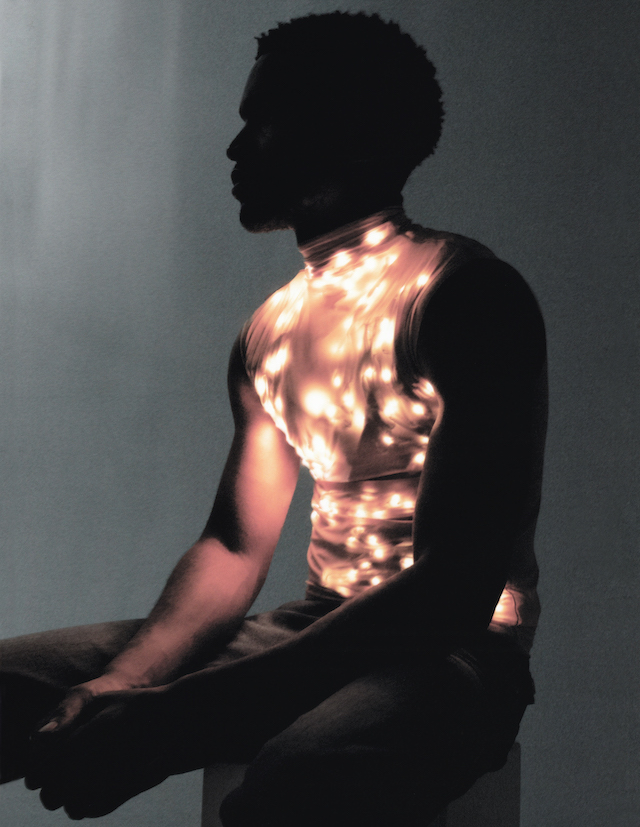

What Bak is doing is trying to catch his breath after a whirlwind year. In the last 12 months, he’s played the lead in Robert Guédiguian’s 1960s-set romantic drama Mali Twist, rubbed shoulders with Timotheé Chalamet in Wes Anderson’s The French Dispatch, and featured in LOEWE’s Spring/Summer 2022 campaign as designer Jonathan Anderson’s unofficial muse. He’s also in two new movies, both of which premiered at the Cannes Film Festival: Cédric Jimenez’s Novembre, a police procedural set in the aftermath of the 2015 Paris attacks, and the luminous Mother and Son, about a single mother who immigrates to France from the Ivory Coast in the late 1980s with her two sons. The latter is directed by Léonor Serraille and stars Bak as Jean, an academic overachiever with a fear of fucking up, who is also responsible for his younger brother Ernest (Kenzo Sambin). Jean quickly becomes the man of the house, filling in for his increasingly absent mother Rose (Annabelle Lengronne), who in turn is juggling night shifts as a hotel maid alongside a new relationship.

“Everything was different about this project,” says Bak, who explains that Serraille, who is white, based the film on her long-term partner. “It’s her boyfriend’s story that she’s got two kids with, so I knew this was personal. She cared,” he says.

Bak’s parents immigrated to France from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Like his character, he is the “big bro” in his family. The second eldest of seven kids, he was born in Villepinte and grew up in Le Blanc-Mesnil, two neighbouring banlieues in “the 93”, on the northern outskirts of Paris. “Like Jean, I grew up fast. I was doing stuff that I wasn’t necessarily supposed to do as a kid.”

Bak is referring to his former life as a professional stand-up comedian, a career he embarked on at the age of 13. “I should’ve applied for the Guinness World Record. It’s not a title that I’m a fan of, but they used to call me the youngest comedian in Europe. They would present me like that when I would go on stage,” he recalls.

The story goes something like this: Bak had heard that two of his favourite comedians, Jamel Debbouze and Gad Elmaleh, were doing a free show in Paris. He and a friend took “the bus, then the train, then the subway” from the suburbs into the city, and parked themselves in the queue. They were third in line, and waited for four hours. When the doors opened, they weren’t allowed in. “I was crushed,” he remembers. Bak drifted across the street to the venue opposite, Le Pranzo. Its then-owner, Emmanuel Smadja, wanted to know what a 13-year-old was doing hanging around outside a comedy club at 11.30pm. Bak said he was waiting for his train, and told Smadja about his dream of performing on stage. “He told me, ‘I’ve got this open mic night upstairs – when you’re ready, you come.’”

Two weeks later, he did his first set. “I had 6 minutes to get ready. I jumped up on stage and the performance was too heavenly! I was like, you can make grown-ups laugh and get a little bit of money for it?!” Bak would place a hat on stage, for tips. “People would put money in the hat, and then I would buy McDonald’s right after on the way home. That’s how I started.”

Bak’s videos blew up on YouTube and Dailymotion. He started getting recognised in the street, and booked on French late night shows. “I was maybe 15 or 16, and I would have to perform stand-up comedy in front of Chris Rock or Sacha Baron Cohen,” he says. His life changed rapidly.

Instead of spending his mornings at school (he got kicked out at 13, anyway), he was showing up to set at 9am, surrounded by grown-ups. “I was working on my computer, trying to find jokes, going to rehearsal, doing fittings, having to be live on TV,” he says. In the evenings, he’d return home and cook dinner for himself while everyone else was sleeping. “That was kind of a troubling experience. As a kid, that’s not necessarily what I would recommend,” he says. “I don’t feel like my childhood was stolen from me, but I remember not hanging out with kids.” He’s wary of falling victim to child star cliché, however. “I don’t want to wake up like Michael Jackson and declare ‘I’m Peter Pan!’ That’s my biggest fear in life.”

As a teenager, Bak took acting classes at the Cours Florent, a private drama school in Paris. “I couldn’t afford them,” he says, but when the French actress Isabelle Nanty saw him on TV, she reached out. She had taught there (Vincent Lindon was one of her former students), and helped to get him lessons. “I had to make a choice,” he explains of the transition from comedian to actor. “My desires, the ones that I had when I was 13, wouldn’t be the same when I was 18. It’s like the stand-up part in me died a little.”

There is little overlap between the Paris comedy circuit and the world of French independent cinema. “Not giving too much praise to America,” but “we don’t have a lot of [people like] Jamie Foxx,” he says. “I hope that my path is going to look like something that’s very unique here.”

It already is. How many former stand-up comedians are also in Wes Anderson movies? Bak tells me that the director is actually his neighbour. “He lives right next to me.” Bak was a fan, and messaged his agent as soon as he found out Anderson was shooting in France. “I sent him a text saying there’s no way I’m not in this movie”. He auditioned, and won a small role as a communications expert. Before he knew it, he was on a $16 million shoot in Paris surrounded by actors he grew up loving, like Frances McDormand, Ed Norton, and Benicio del Toro. “You’re like a kid in a candy store,” he says. And in fact, there was candy on set. “The first encounter where I met Bill Murray, I was talking on the phone. I saw him waving at me with a box of chocolates. I was looking behind, thinking, surely ‘That’s not for me!’”. It was.

Mother and Son – set to be released in the UK early 2023 – is another milestone in Bak’s journey, and is his most complex and finely tuned performance yet. In the film, Jean learns the hard way that he’s no longer a boy. For Bak, the experience is familiar. “I was in this environment with older people, having to deal with contracts, not being screwed over, not having my kindness taken for weakness,” he says. Making money came with responsibilities his peers didn’t understand. It made him grow up fast – so much so that his friends still tease him, declaring him an “old soul” at 25.

“They’re always saying ‘You’re like, 60! You never want to go out!’” he laughs. This summer, his plan is to spend less time online, and more time reading. “I just got done with The Most Secret Memory of Men by Mohamed Mbougar Sarr, it’s a beautiful book about this Senegalese author that enters the French literature scene. A scene that he doesn’t belong to, necessarily,” he says.

He is drawn to these diaspora stories, which he describes as “still very young in terms of French cinema”. He cites films he’s made like Mali Twist, The Mercy of the Jungle, Roads, with Fionn Whitehead and Sebastian Schipper, and now Mother and Son as examples. He doesn’t want to “talk bad on French cinema” but says growing up as a Black kid in France, he’d rarely see people who looked like him represented in the movies. “If it wasn’t for American blockbusters, you don’t see yourself,” he states. “I love French cinema, and I’m a Godard fan, I’m an Assayas fan. But these people that live next to me, that I know, or that you might run into every day – they’ve got beautiful stories to tell too. I don’t get why we don’t see them on the screen.”

It’s why a project like Mother and Son feels like a gift. Like Rose, Bak’s own mother immigrated to France and worked as a cleaning lady in the late 1980s. “In some ways she’s been damaged by France, too,” he says. He describes seeing her at the premiere in Cannes as “the most moving moment of my career” and says that after the screening, they both cried in each other’s arms. “She could see some part of her life on the big screen. That’s never happened. It doesn’t happen like that. That’s what I’m pushing for.”

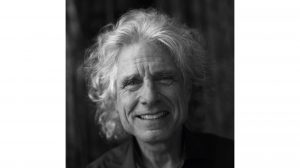

Photography Anatheine

Styling Julie Velut

Grooming Lorandy for Charlotte Tilbury

Styling assistant Coline Faucon

With thanks to The Production Factory, London

This article is taken from Port issue 31. To continue reading, buy the issue or subscribe here