Celebrating the launch of their new book, Alan Hess and Michael Murphy discuss the democratic, technicoloured optimism of Googie architecture

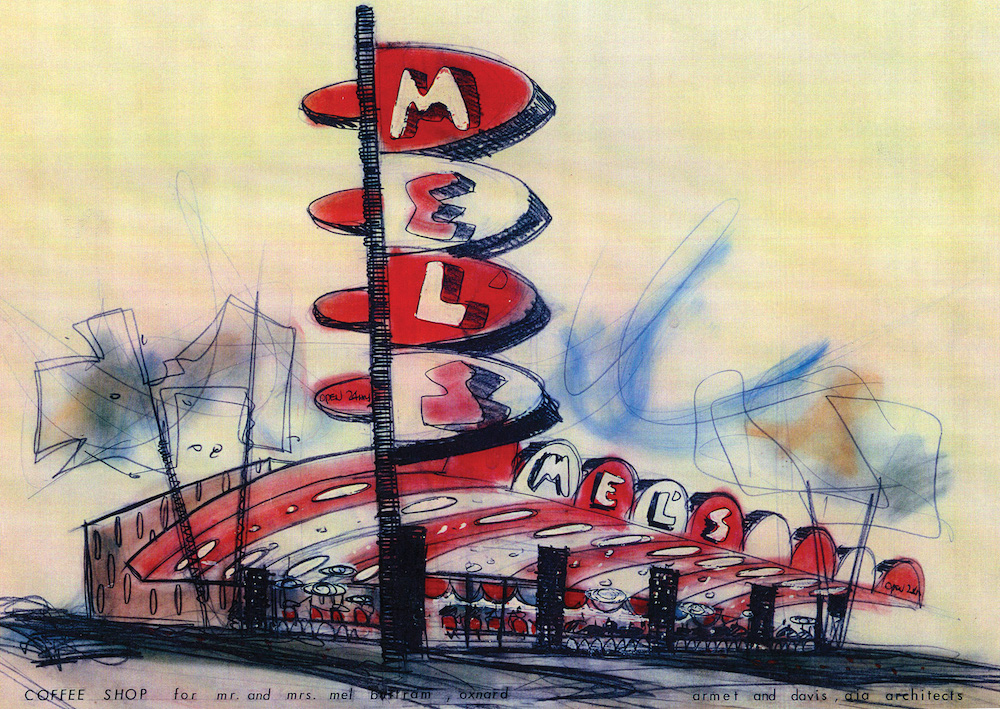

On a recent balmy spring evening, architect Alan Hess and author Michael Murphy stepped out of Mel’s diner in Santa Monica. The late-night 50s eatery is eye-catching, with its bright neon sign, angular roof and sheer glass walls. A beacon on the boulevard, it is one of the first buildings to signal the end of the United States’ famous route 66. Looking at Mel’s, it’s easy to find yourself admiring the Americana of it all.

But what is this distinctive architectural style that characterises Mel’s? That would be Googie.

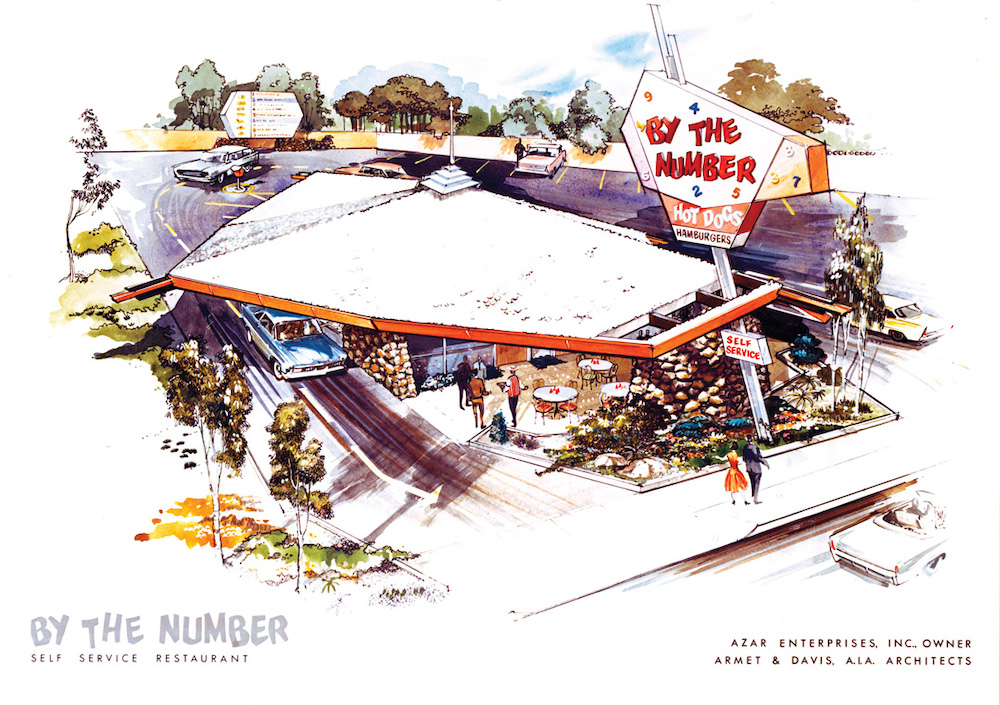

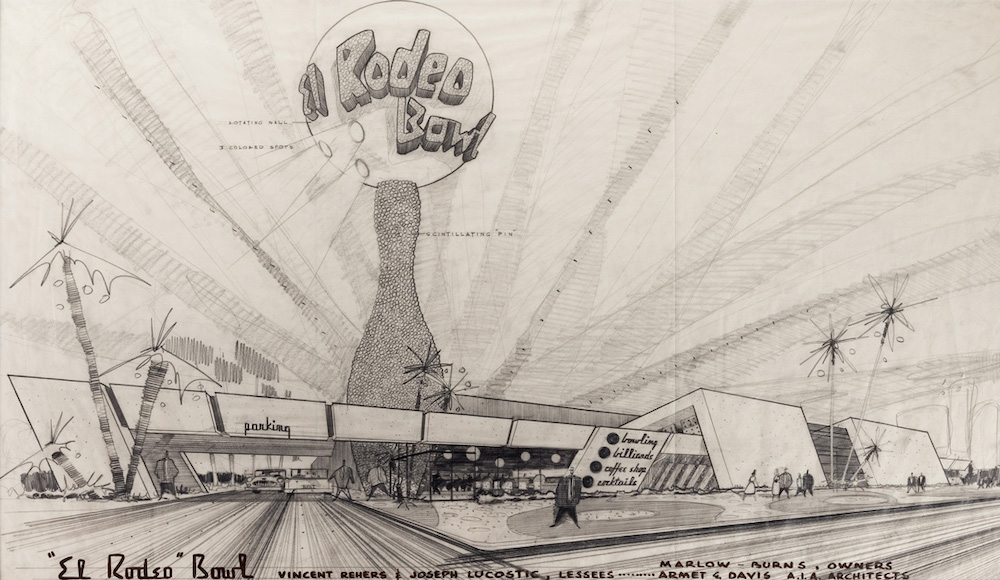

While many may not know the name, most are familiar with the style that is almost as iconic to LA as a palm tree. But even if you’ve never been to LA, the style is deeply engrained in the imagination: think buildings of chrome and glass, dramatic angles and bright colours, often emerging from the side of roads with unmissably tall neon signs.

Such buildings captured a technicoloured optimism that existed of a certain era: post-world war II America. In this stretch between the 40s-60s, America was wealthy; the middle class had expendable income, the car industry boomed, and with man landing on the moon, the sense that the space age had arrived was palpable. These futuristic ideals and optimism had their architectural expression in Googie, which was often found in the design of coffee shops, bowling alleys, car-washes, restaurants and drive-throughs.

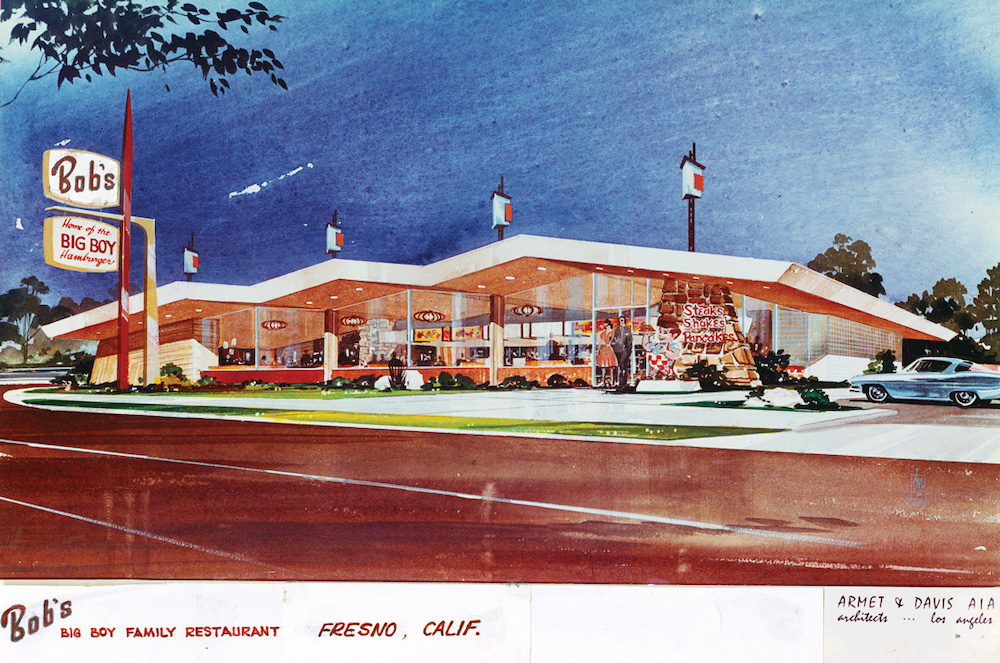

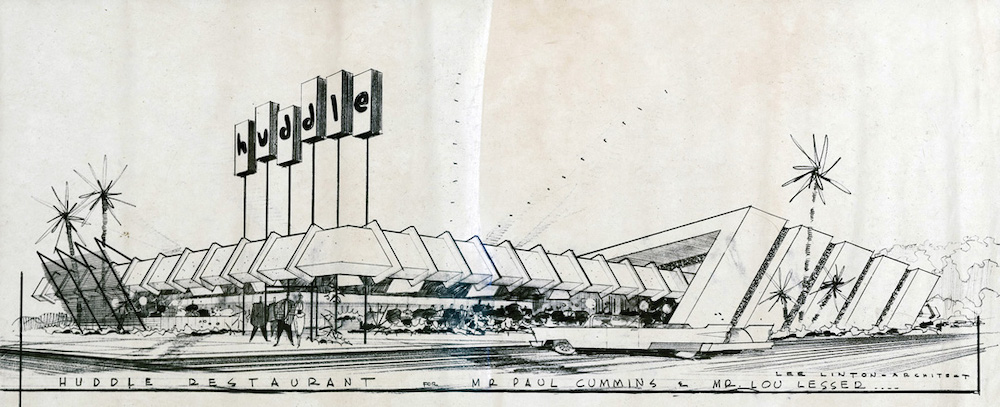

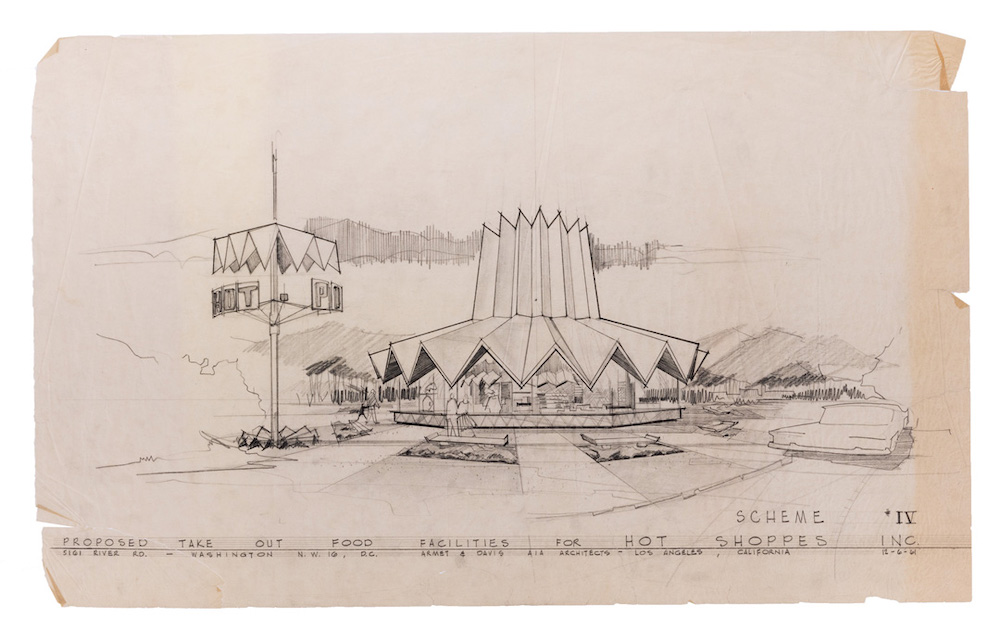

While the style is undeniably a SoCal aesthetic, it soon spread throughout the US, defining many motels, diners and gas stations. However, the style was short lived, eventually falling out of favour. Today, few original Googie pieces remain. Hess and Murphy were at Mel’s to celebrate the launch of their book, Googie Modern: Architectural Drawings of Armet Davis Newlove. The work is a collection of drawings from the archives of architectural firm ‘Armet Davis Newlove’, which are responsible for some of the most iconic examples of Googie.

Hess and Murphy spoke to Port shortly after the launch about their collaboration and of the enduring significance of this unique movement in Modernist architecture.

What makes Googie such a unique form of architecture?

Michael Murphy (MM): This was a special time. Post-war America was prosperous, people could afford things: new houses, new cars, and they could hit the road and drive. They were in pursuit of the newness and did not want to look back, and the architectural style reflected that.

Alan Hess (AH): Googie is authentic Modern architecture for everyone. These buildings were for the average person but still captured the delights of the modern age – the freedom and mobility the automobile brought to everyone, the optimism about new technologies and their promise of a new, better life for everyone. Googie is idealistic, or better yet, democratic.

Googie seems synonymous with car culture; they’re often these bright retro buildings on the side of boulevards. Why is this?

AH: Modern architecture expressed modern technology. The automobile was its most important example. People went to the movies, visited their banks, picked up their laundry, and grabbed a meal in their cars. So, of course those drive-ins and coffee shops were on busy boulevards – that’s where the customers were. And the signs – always integrated into the architecture – made it easy for those customers to know where to go.

When I think of Googie – I think of the Theme Building at LAX; I also think of the TV series The Jetsons. Take this as a comment, not a question.

MM: Exactly, this captures the idea of Googie and the future – so it was about the airport, about travel, The Jetsons also captured the architecture, and it got us excited about what was ahead. It was an optimistic time. There were many Googie architecture buildings in the San Fernando Valley where the creators of the Jetsons, Hanna-Barbera, officed.

AH: Yes, the animators didn’t have to go far to be inspired by actual Googie Modern architecture! There were quite a few Googie coffee shops in Hollywood and the San Fernando Valley at the time.

You speak of how Googie reflected this sense of optimism in post-world war II America. Tell me a little about that?

AH: I distinctly remember how Googie restaurants like Bob’s Big Boy (I grew up in Pasadena) impressed me as a kid. They were open and spacious with huge walls of glass – the outside and inside blended into one. They were exciting – you really felt like you were living in a new modern age when these were a regular part of your life. We went there as a family for a treat about once a week.

Googie is common in SoCal, but no city more than LA. Can you tell me about the architectural styles connection, in particular, with Hollywood?

MM: Googie architecture was designed as a bright stage to advertise itself, I think Hollywood very much does the same thing.

AH: Carolina Pines on LaBrea, Tiny Naylor’s across the street on Sunset, the original Googie’s restaurant on the Sunset Strip where Elvis, Marilyn Monroe and James Dean hung out — there were no places more cool in Hollywood than these Googie restaurants. They show up in movies and early television shows to establish the unique Hollywood character.

Why did Googie architecture stop?

AH: Back then, critics didn’t like it — actually they didn’t understand it. It was too free, too popular, too commercial to be “serious” architecture, they thought. Today we know better. It’s interesting because now there’s Googie’s trademark experimentation with new shapes and modern materials in the work of Rem Koolhaas, Zaha Hadid and other Modern architects today.

Not all of the projects depicted in the book stand today, a lot have been razed, especially in the latter part of the last century. I wonder, with society’s ever-changing demands from spaces, why should we fight to preserve Googie buildings?

MM: I think in today’s age, aspirational architecture seems to land on hillsides overlooking the city or in museums. We don’t demand better spaces because we are not taught what is possible and how to demand it, and what the effects of bad design has on our daily life. Googie architecture was designed to enrich the lives of the populace. There is not a single Googie building that was demolished where they built something better.

Do you have a favourite piece of Googie – either still standing or demolished?

MM: I am a sucker for all of them, but if I had to pick, my favourite is Holly’s Coffee Shop on Hawthorne Boulevard. It has a great narrative, it was opened in 1956, had an amazing roofline, signage, and interior design. It also has the advantage of being the opening and closing scene of Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction! But sadly it didn’t last. It was demolished in 1999 and is an AutoZone store now.

AH: The drawing of Mel’s in Oxnard is one of my favourites in the book. It’s a free-hand drawing and just radiates the energy and joy of living in that age when anything seemed possible. We’ve lost too many Googie buildings in LA, but at least now we’re beginning to see them protected as city landmarks and even restored to their original condition.

Googie Modern: Architectural Drawings of Armet Davis Newlove is available through Angel City Press