Eric Rhein’s new book tells the personal story of an artist’s life during the time of AIDS

There always tends be a few key moments that drive every creative’s practice. For Eric Rhein, a multimedia artist who grew up in New York’s Hudson Valley, it was the childhood summers spent between the Ohio River Valley and the Appalachian Mountains of Kentucky. “These fertile regions are richly linked to the natural world,” he says, “and are influences that emerge throughout my artwork.” So much so that Eric has long explored these naturalistic tendencies through a broad mix of mediums, flitting effortlessly from wire drawings and sculpture, to photography and collage. His works have now been exhibited widely in the US and internationally, with countless features in The New York Times, Huffington Post, Artnews, Vanity Fair and Art in America to name a few.

Another defining moment for Eric arose when he moved to New York City in 1980, aged 18. Pursuing a scholarship at School of Visual Arts, he began to explore new artistic outlets, like that of building butterfly puppets for George Balanchine’s production of the ballet, L’Enfant et les Sortileges (which translates to The Spellbound Child). “I became saturated in the vital East Village arts scene,” he says. “It was a unique community that permanently altered the city’s cultural and creative landscape, which was in turn deeply altered by the AIDS crisis.” Eric tested HIV positive in 1987 at the age of 27, and with his diagnosis, all of these previous inclinations towards the natural world – alongside themes of resilience, vulnerability and transcendence – grew with even more pertinence. This manifested into a new body of work, titled Lifelines.

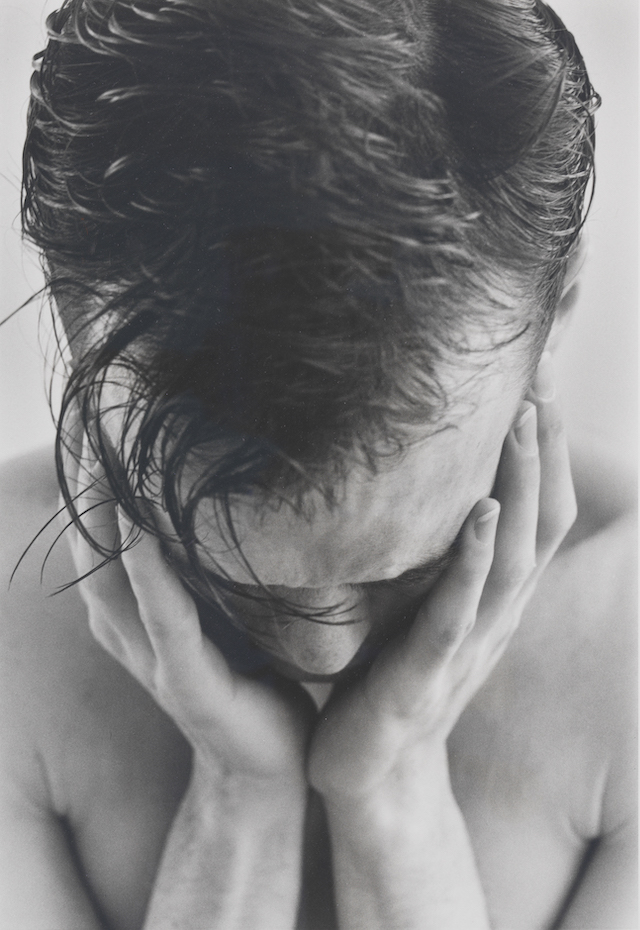

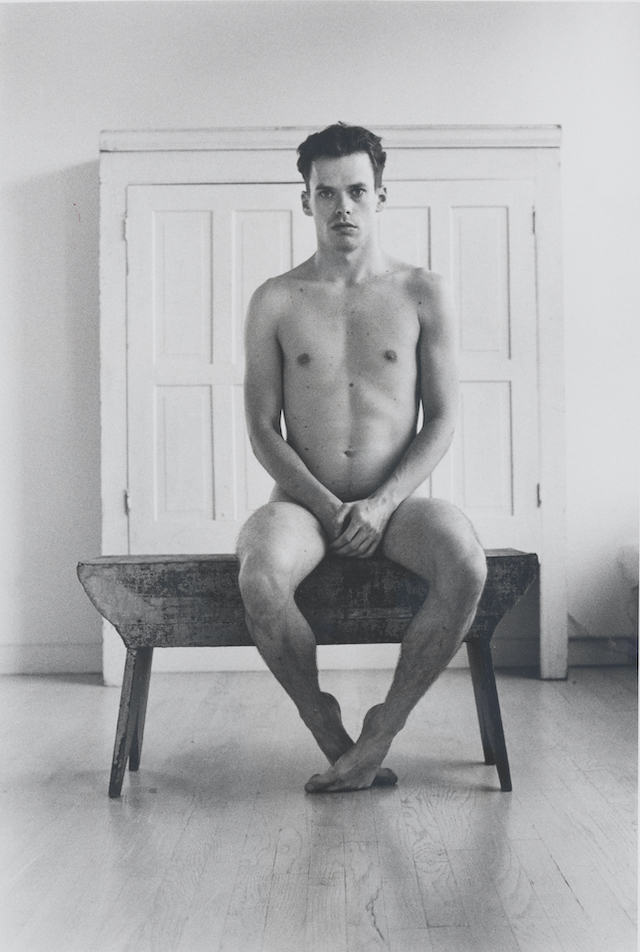

A compilation of tonal, monochromatic photography and mixed-media, Lifelines is a series of artworks taken and collected between 1989 and 2012, now published as his debut monograph by Institute 193 and featuring essays from Mark Doty and Paul Michael Brown. The project emerged after shooting his first self-portrait, named Seated, captured in 1992 after this mother had gifted him a Nikon 35mm film camera. At the time, he wasn’t quite aware of the fact that he was about to embark on a three-decades-long piece of work, lensing his own experience of living through AIDS, as well as his friends and lovers. But in doing so, he ended up recording an important and personal period of history.

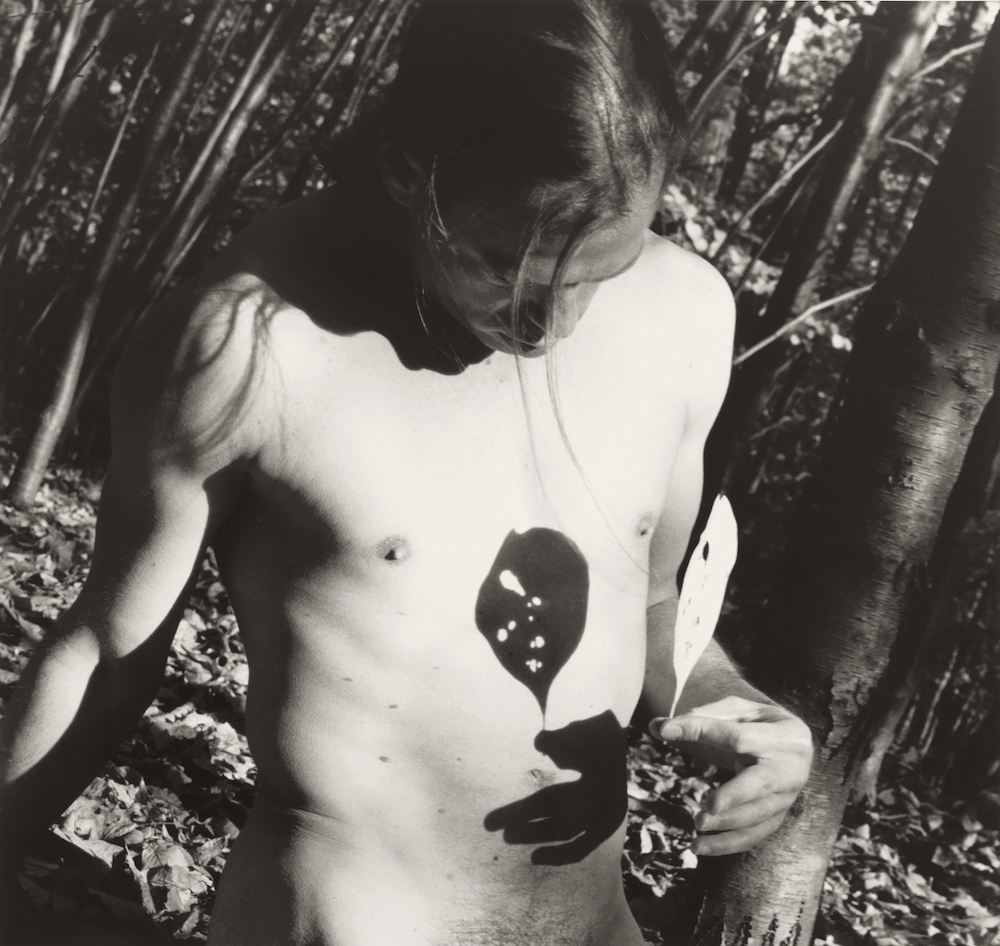

The photographic work featured in Lifelines was shot over many years and in a variety of circumstances. To detail as such, Eric was sure to include marked dates with each corresponding image, building a comprehensive timeline of an artist’s life during the time of AIDS. All of which is processed as silver gelatine prints, whereby the grain protrudes with a diffused, dream-like quality, endorsed by the photographer’s reliance on natural light. “In some of the photographs, our bodies, enveloped in sheets, are illuminated within sun-drenched interiors,” he notes, “while in others, photographs were lit through windows, doorways or tree branches.”

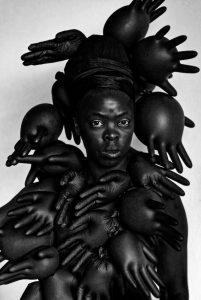

Having held back on publishing this work previously, Lifelines now depicts the full breadth of Eric’s experience: starting from the diagnosis, right through to his “return to life” brought on by the arrival of protease inhibitors in 1996 – a class of antiviral drugs that are now widely used as a treatment. “Some of the photos show me at moments when I was physically fragile, and others were taken after my ‘renewal’, when I was more robust,” he says. Meanwhile, several of Eric’s subjects within this project are no longer with us, and many of which were HIV positive when their portraits were taken.

One image in particular, William – Silhouette, is a photograph of William Weichert, captured in 1992 during a summer spent on Martha’s Vineyard. Eric reminisces of how his lover wanted to be a pop star: “he wrote songs with lyrics like Hair Like Oprah, Butterfly Kisses, Love From Above and What About Tomorrow”. He passed away from complications of AIDS in 1996 at the age of 28, not long after the lifesaving protease inhibitors were released, which sadly weren’t effective for him.

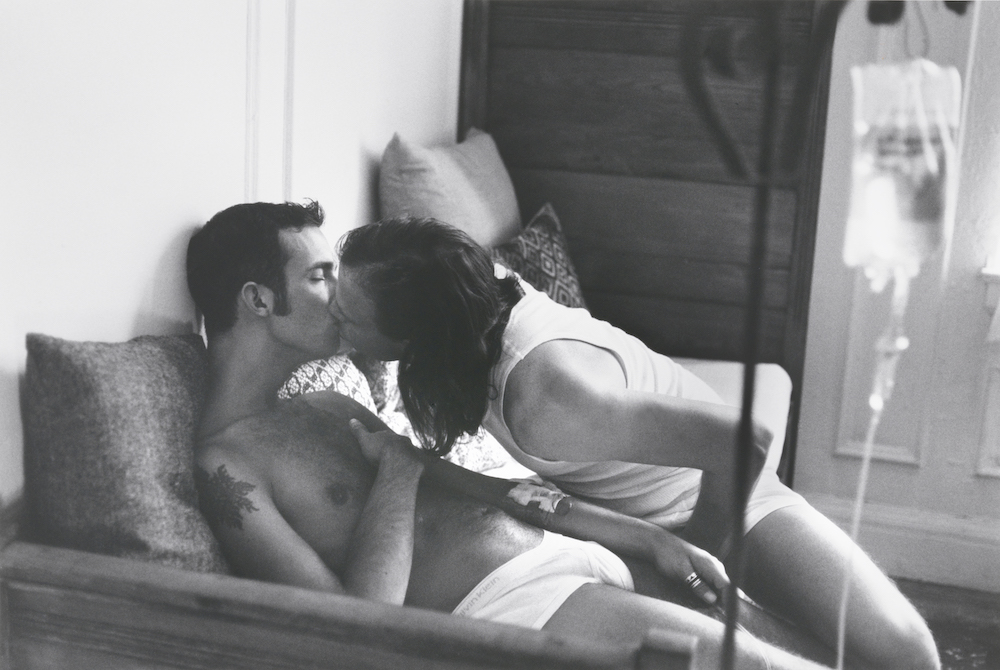

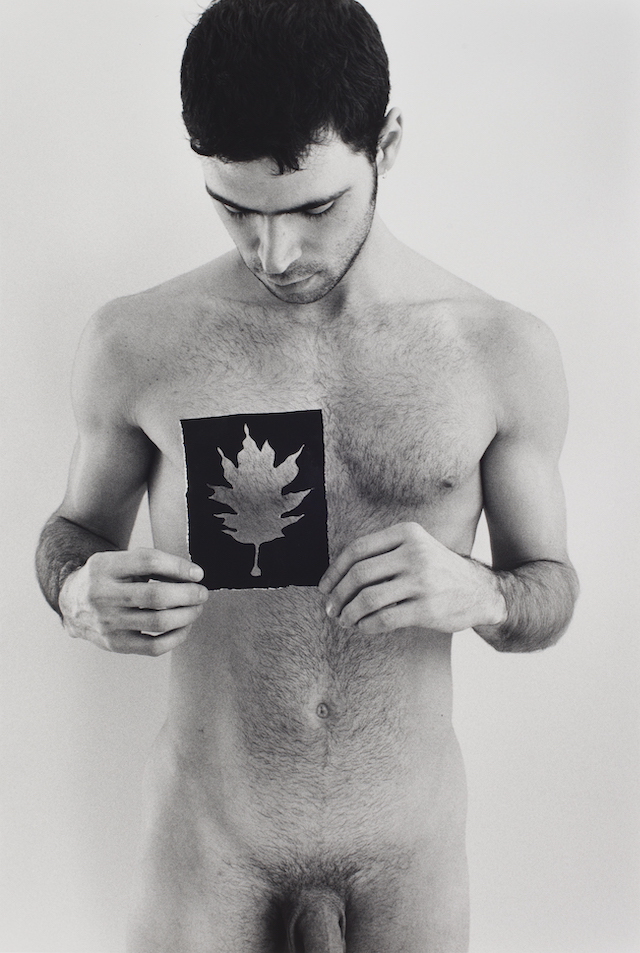

Negative Space is a further picture shot in 1993 of his then-boyfriend Jeffery Albanesi. The title is suggestive of the fact that Jeffery was HIV-negative during this time – and still remains so – and looks at the tricky (and reassuring) relationship of being with a HIV-positive man. Meanwhile, Kissing Ken, from 1996, was lensed over the summer while Eric was part of a study for the incoming protease inhibitors, which successfully lowered his viral load, causing it to become undetectable. “While I was rapidly gaining health, my then-boyfriend Ken Davis had yet to be accepted into a study and was in declining health, which necessitated him having daily HIV medication drips. We’re shown in the apartment that I shared with I’m in East Village.”

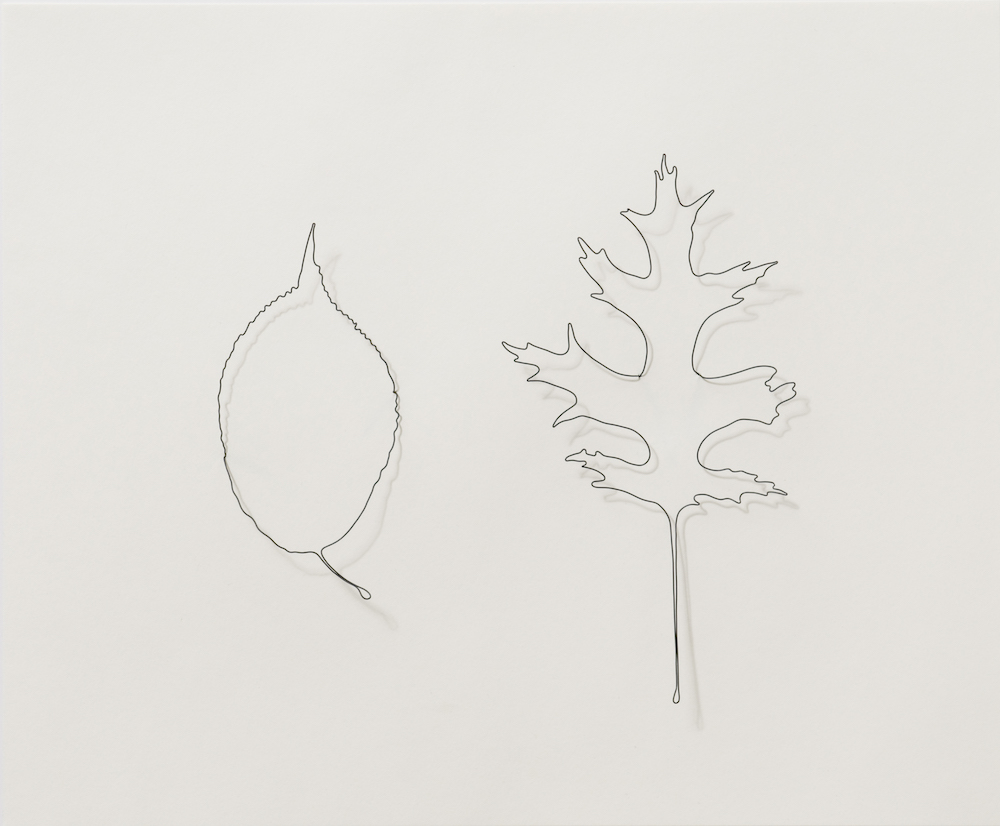

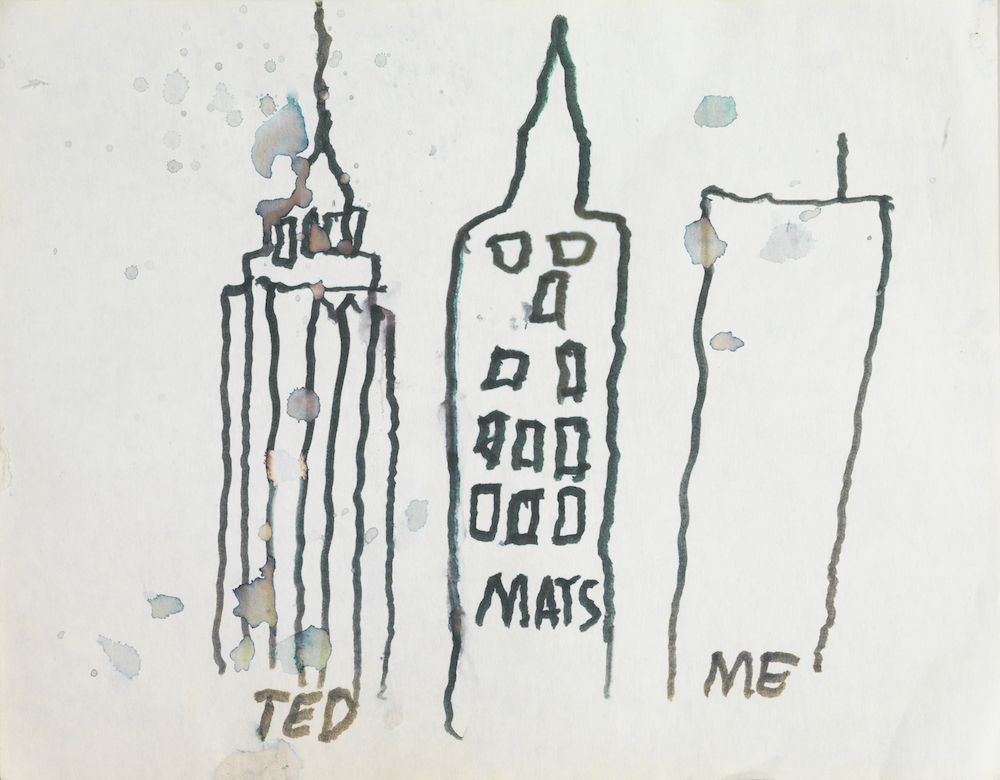

These intimate and autobiographical works are housed amongst a complimentary mix of material-based pieces – like water-splashed marks and collaged findings. Each was composed from his hospital bed in 1994, while his health was extremely fragile. The AIDS memorial leaves, too, are of great significance to the artist, notably as they honour the people who Eric has known to have died with complications from AIDS.

It becomes evident throughout Lifelines, and with all of his activist-driven endeavours for that matter, that Eric is devoted to telling the difficult narratives around AIDS. He was close to death, and he wants nothing more than to put this new body of work in front of an audience who will appreciate his story.

Lifelines is published by Institute 193 and can be purchased here.

Photography by Eric Rhein.